“The Ones Who Walk Away”: Phantoms, Ambivalence & Hope within Exiled Egyptians in Istanbul

It was in the Spring of 2018 when one of my professors assigned us to read Ursula K. Le Guin’s short philosophical fiction, The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas. Published in 1973, Le Guin’s allegory depicts a seemingly utopian city, Omelas, where all its residents live prosperously and happily. Nonetheless, the reader gradually discovers that the city’s prosperousness is essentially built upon the torture and suffering of one single child locked up in a broom closet. The people of Omelas also come to comprehend this reality, and only a tiny portion of them, moved by a strong emotion of guilt, decide to withdraw from the city altogether (Le Guin, 1973). Despite its shortness, this allegory features an ever-lasting situation in which individuals grow to recognize numerous spots of injustices inborn in the larger structures of their lives. In their instinctual strive for happiness and fulfilling a good life, individuals respond and act differently towards these many broom closets. Whether they choose to bypass these dark closets or decide to change something about them, we are usually left with a flood of emotions that involve moments of a sense of agency and occasions of complete helplessness. Annabel Herzog writes, "The case of ‘Omelas’ reveals the hopelessness of change and the ambiguity of resistance against a society believed to be optimal. What can be done against a system like that of Omelas except to leave, and what does leaving mean?" (Herzog, 2021, p. 76).

In the summer of 2018, I emigrated from Egypt and settled in Istanbul. Following the Eid morning prayer and right in front of the ancient Egyptian obelisk centering the square of The Blue Mosque, I stood rapt in awe while gazing at the large number of Egyptian expatriates occupying the space. On the 3rd of July 2013, following street protests, the army toppled the former first democratically elected president Mohamed Morsi and suspended the constitution. Subsequently, massive arrest campaigns, street violence, and mass murder started taking place in the months after, targeting senior leaders and members of the Muslim Brotherhood together with variant opponents of the new regime. In consequence, the Turkish regime instantly showed sympathy and support, condemning the military coup. Thereupon, Turkey received thousands of Egyptian expatriates, many of whom were Islamists and members of the Muslim Brotherhood. According to senior Turkish officials quoted in the media in 2019 and 2020, some 15–30,000 Egyptians live in Turkey (Ayyash, 2022). Expatriates imagined Turkey as a fertile space for possible transnational activism and political engagement with their homeland.

The ones who walk away from Egypt are different from their Omelian counterparts. A good number of them did not choose to leave but were rather forced to. They certainly did not escape a utopia where all citizens are thrilled and well-off. But what one finds common between the fictional work and this reality is the ghost of their homelands and the memory of the suffering child in the broom closet, personifying a state of ongoing structural violence over which a rapid and radical urban innovation process is taking place. In this paper, based on my ethnographic research, I try to take it from where Le Guin ended and look into the new lives of deportees. I dig into the nuances of what it is like to be an Egyptian political migrant living in Istanbul. Looking at the potentialities between the "not yet" and the "no longer" and the spaces between hope and despair, my prime purpose is to fathom how these exiled Egyptians engage emotionally with the political situation in Egypt, given that their physical presence became elsewhere. I argue that most of my interlocutors were constantly haunted by the past, which evoked a liminal state of being, and the only way out for many of them was to abandon the Egyptian political sphere and find potentialities of hope elsewhere.

The Presence of an Absence (Haunted)

After a long transportation journey, I finally arrived at “Beykoz Kundura,” located on the Northern end of the Bosphorus shore in the district of Beykoz. “Beykoz Kundura” is an industrial, cultural area with a spacious complex encompassing numerous film studios. I entered the filming location, which features a dull prison building with lots of dimly lit prison cells and strong cigarette smoke. A group of exiled Egyptian filmmakers were filming a drama series titled Dungeon 55 that narrates the story of several political prisoners and their everyday struggles with a psychopathic police officer. During the break, Ali, an old actor who played the role of a jailer in the drama series, breathed a deep sigh of sorrow and looked at Jamal, his fellow actor, sharing the heavy thought that had just crossed his mind. He expressed his sympathy toward the political prisoners in Egypt. Ali revealed to his friend that the atmosphere of the filming location and the role he played made him acutely fathom what it is like to be a political detainee. Specters were always looming somewhere between the words in the site visits and during the interviews. The figure of the ghost or the absentee often took different forms. Sometimes, it is a friend or a relative who is politically detained. Other times, it was a martyr. Specters also came in the form of flashbacks to street protests, the January revolution itself as an abstraction with a package of connotations and meanings or an earlier subjectivity tied to it.

Bringing up the influence of absences on reality and the return of remnants of the past in the presence, Jacques Derrida coins the concept of “hauntology” in his seminal work Specters of Marx (1993). The term “hauntology” is a portmanteau formulated from the fusion of two words. The first is “haunt,” which refers to the appearance or the materialization of a ghost or an absent figure. The second word is “ontology,” which is concerned with the nature of being. In that sense, the term as a whole translates to “the persistence of a present past or ‘the return of the dead’” (Sami, 2021, p.380). Mark Fisher reflects further on Derrida’s choice of the term. He remarks that Derrida was attempting to challenge the conventional “ontology,” which illustrates being exclusively based on existence and presence while dismissing the profound role that absences play in this illustration. To most of my interlocutors, the Egyptian public space, with all its materiality and sentimentality, is distant, absent, and only accessible through virtuality or digital platforms. While carrying a digital ethnography, however, it was quite compelling to see how particular spaces in exile, like the art sphere, carried phantoms that had a recognizable influence on my interlocutors.

To most of my interlocutors, the Egyptian public space, with all its materiality and sentimentality, is distant, absent, and only accessible through virtuality or digital platforms.

One of my interviewees, Amir, who works as an art director and was among the crew working on the aforementioned drama project that tackles the issue of political imprisonment in Egypt, disclosed to me that he had to sleep in the filming location, a prison. Amir illustrates that men often suppress their emotions and do not prefer to share them with their fellows. Yet that night, he could not sleep and recognized his friend who could not sleep either. Both Amir and his friend were imprisoned before they left the country. “The moment each of us takes a break, the general atmosphere immediately reminds us of voices embedded in our ears,” he took a deep breath and continued (Amir, 27).

Living on a Threshold (Perplexed)

Ambivalence and unclarity were recurrent effects that many of my interlocutors expressed during our interviews as a consequence of this hauntological condition. While conversing with Ahmad, a 30-year-old actor, he told me, “I am like the ones who danced in the stairwell, neither seen by those above nor those below… I cannot go back to my country, and I am not able to live comfortably in Turkey either. I am not a Muslim Brother, nor am I isolated from them. I am always in the middle of everything” (Ahmed, 30). I tried to unpack these emotions of perplexity and confusion through the lens of Turner’s “liminality” and Szakolczai’s “permanent liminality.” Liminality in the fieldwork appeared in two forms.

The first aspect of this liminality lies in the conflictual emotions of wanting to both remember and forget. Hassan, a 25-year-old art director, revealed that he genuinely wishes to completely forget the day of the Rabaa massacre, which he survived. Towards the end of our conversation, however, he told me that he found a soundtrack on the internet titled “The Carnage.” The sound collage combines the sounds of hovering military aircraft, bullets, screams, prayers, and sirens from the day of the Rabaa massacre. Hassan shared that he finds himself searching that track occasionally and listening to it despite his deep desire to let go of that memory. The second bearing of liminality was hesitating whether to hold on or let go of a particular subjectivity built during the years of street activism preceding exile. One of the artists I interviewed demonstrates an internal conflict that constantly gives him a strong sense of confusion and fogginess. He illustrated that he is interiorly living in two parallel universes. On the one hand, he is getting married and planning to travel and build a stable life for his family. On the other hand, his parents nurtured in him an identity of a revolutionary reformer, and he feels as if he is gradually losing this identity as he moves on with life. He clarifies that he continuously asks himself, “Where is the revolutionist? Where is the one who walked the streets and wanted to change something? This past self is almost dying" (Amir, 27). I asked him if he wanted this persona to die. He answered that he did not have an answer to this question even though it kept crossing his mind. The only partially satisfying answer he has reached is that he will continue building a stable life. Yet the moment a revolution outbursts, he shall be the first to join, leaving everything behind because this is where he belongs.

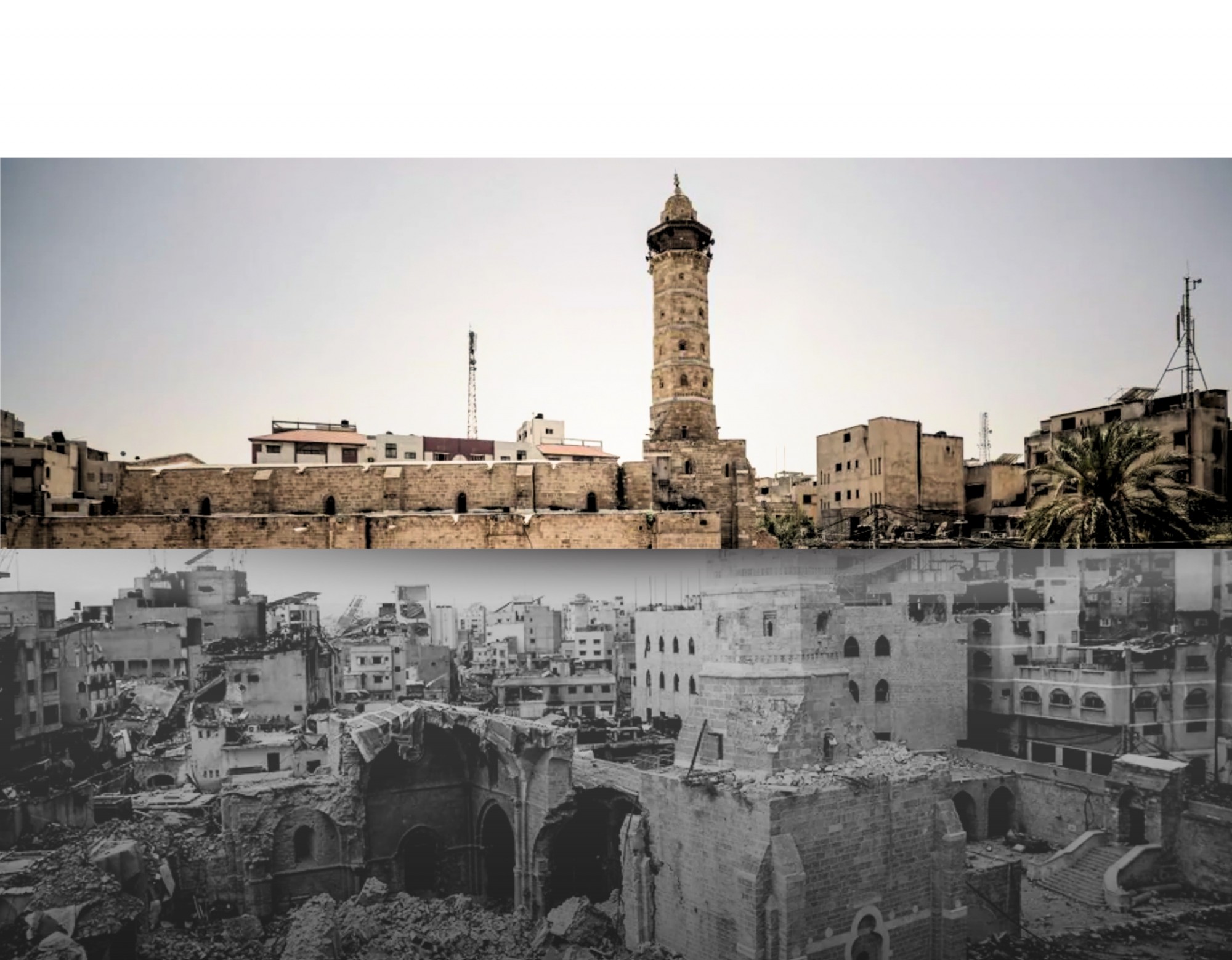

Clashes in Cairo on the bridge leading to the Rabaa al-Adawiya Mosque, 2013

Source: Amr Abdallah Dalsh, Reuters

Hope in the Hopelessness, Agency in the Helplessness

While attending one of the social gatherings carried out by a group of Egyptians living in Istanbul as a participant observant, Salih, a father of three in his late 40s, used a metaphor to describe why he thinks that most of the collective efforts done by Egyptians in exile are ineffective. Salih gave the analogy of a group of expatriates coming from a desert environment who have just landed on a new island with which they are completely unfamiliar. Immediately upon their arrival, the group started working using the exact surviving techniques they were previously living with before leaving their homelands. None of the new arrivals paused to observe the new space and fathom its nature, which was radically different from their past habitus. Neither did any of them thoroughly grasp that their stay on the Island was permanent, not temporary. This analogy is quite powerful as it summarizes the state of many of my interlocutors who are regularly haunted by the absentees and are stuck between a past of activism leading to forced migration and a present reality of exile that is no longer temporary and legal precarity of many young Egyptians who have had their passports expired and could not renew it from the Egyptian embassy in Turkey as a punishment for their earlier political participation.

In spite of the survival guilt that comes with the visiting phantoms and the confusion that accompanies a condition of permanent liminality. I argue that the closing of Egypt’s political and public sphere continually sparked feelings of hopelessness and defeat, which compelled many of my interlocutors to look for strength and capability elsewhere. In the fieldwork, three characteristics of becoming were evident. The first one is the desire to “become something,” which was typically mentioned in relation to professional development, success, holding some sort of material power, etc. The second aspect of becoming is the impulse to “become normal,” which speaks to their intense desire to recover and rid themselves of an identity that is trauma-oriented. The third one is about wanting to let go of their previous subjectivities and affiliations. Likewise, many of my interlocutors avoided thinking about change on a large scale and developed a preference for microscopic transformational activity in the domains in which they excelled, remolding the idea of transnational activism and reproducing new ways of imagining agency and change in times of hopelessness and helplessness.

References

Ayyash, A. (2020, August 17). The Turkish future of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood. The Century Foundation. https://tcf.org/content/report/turkish-future-egyptsmuslim-brotherhood/

Derrida, J. (2012). Specters of Marx: The state of the debt, the work of mourning and the new international. Routledge.

Herzog, A. (2021). Dilemmas of political agency and sovereignty: The Omelian allegory. Theory, Culture & Society, 38(4), 71–88.

Le Guin, U. K. (1973). The ones who walk away from Omelas.

Szakolczai, Á. (2017). Permanent (trickster) liminality: The reasons of the heart and of the mind. Theory & Psychology, 27(2), 231–248.

Sami, H. G. (2021). The city and its martyrs: Cairo as the site of an alternative historiography in Omar Robert Hamilton’s The City Always Wins. Journal of the African Literature Association, 15(3), 379–393.

Mariam Agha

Mariam Agha is a Ph.D. student in Sociology and a teaching and research fellow at Ibn Haldun University in Istanbul, Turkey. She graduated from the American University in Cairo with high honors in Anthropology and a minor in Political Science. She th...

Mariam Agha

Mariam Agha