Architecture of Hassan Fathy: Reproducing Tradition in the Modern World

After centuries, we have come to a point in which the personality, tastes and preferences of the modern individual are passivised and the search for basic beauty is instrumentalised. In this process, which roughly started with the Enlightenment and became institutionalised with the modernisation, we witness a type of the individual detached from the social context and whose entire focus is on themselves in practice, while putting the individual-human at the centre in discourse. At this point, the main issue is how the modernisation process is. Sadettin Ökten refers to this issue in one of his writings as follows:

"If you do not produce an object, that object comes to you from somewhere else. It either comes from repetition or imitation. But there is an intrinsic value behind what comes, which we cannot see, and you cannot know that value. As you use that object, that value transforms you, that is, first it transforms your behaviour and then the value judgement affecting your behaviour" (Ökten, 2014).

In essence, this is the problem that cultures, whose origin is not the same, cannot carry cultural products that they do not produce themselves. Seyyed Hossein Nasr states that the tension created in the minds and souls of Muslims by the confrontation between modernism and traditional Islam is directly reflected in the cities as chaos. Also, he refers to the responsibility of people who will be opinion leaders in the field of urban aesthetics and architecture and who have economic and social influence on the majority regarding the architectural and urban crises prevailing in the Islamic world (Nasr, 2009).

In general, modernisation, which represents a radical break from the traditional, refers to multifaceted processes of change and transformation. In this context, modernisation includes positivism, nationalism, capitalism, urbanisation, secularism, specialisation and many similar processes. It is a subject that requires expertise to fully comprehend the roots of introduced concepts and aesthetic judgements. When it comes to our cities; architects, artists, planners and policy-makers are the primary people who will design the aesthetic structures and make them applicable. When building cities and designing structures, proposing alternatives to the existing system alongside modern tools, while also being aware of their own value system, is undoubtedly something only a few architects can do.

In terms of asking the right questions to modern discourses and producing alternatives, Egypt appears as an exemplary country for such problems. With its civilisation in the early periods of history and the capital it has created with Islamisation, Egypt is a region that needs attention for its architecture, both in terms of its relationship with the idea of nation developed by modernism and its identity formed in the post-Ottoman colonial period. And in a such context, when modernism was particularly popular around the world, Hassan Fathy was an architect who went beyond the ordinary and showed that another form of architecture was also possible.

Architecture of Hassan Fathy

Hassan Fathy was born on 23 March 1900, in Alexandria as the child of an Egyptian Arab father and a Turkish mother. As a child of a wealthy family, Fathy wanted to study in the department of agriculture initially but later, he studied architecture at a technical university in Cairo. After graduating in 1926, he worked as an engineer for a while and then was appointed as a lecturer. During this time, both his interest in nature and unplanned urbanisation he witnessed in the places he visited, as well as the inadequacy and helplessness of people in the face of modern means of production, motivated him to go beyond the common and to look for ways to re-establish an aesthetic environment that everyone could easily access.

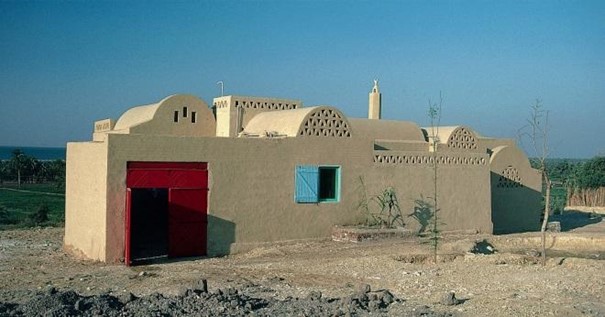

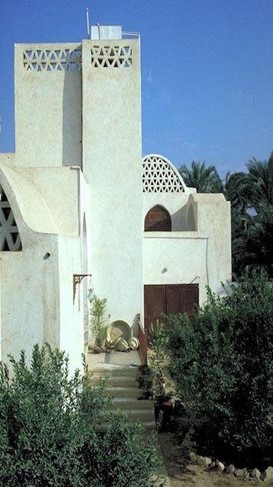

Abu Riche Mosque in Egypt, one of the mosques built in low-income areas by minimising the project cost and involving local people in the construction.

Fathy’s main focus is primarily on ordinary people with lack of adequate financial resources. Hence, he developed two architecturally important things accordingly: Inspired by Mamluk and Ottoman architecture, one is the latticed bay windows, double-storey halls and courtyards which provide natural air conditioning.

The other is the upper covering system, which Fathy designed with arches, vaults, and domes made of affordable and formless terracotta or stone. While doing so, he followed a different path by designing projects that respond to current needs by also including the end-users in production, and with completely local materials and craftsmanship.

Construction of vaults without mould

Hassan Fathy, well-known in the international literature of "architecture for the poor", simultaneously produced many projects for upper-income levels and applied formal and structural details that he was seeking to these buildings. Thus, we can also see that his architectural pursuits were not only dependent on the economic conditions.

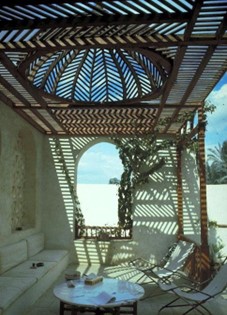

One of Hassan Fathy’s personalised residences, when we look at the interior design, we can see that he includes traditional art elements and adapts them to contemporary use.

One of Hassan Fathy’s personalised residences. The pergola he designed by imitating the symbol of Egypt, the palm tree.

The architect, who argues that regardless of the project, the project cannot be thought of independently from its end-users and that the priority is the life there, states in one of his writings: "Those who would transform the countryside could do so by loving the fellahs [peasant] enough to live with them, settling in the countryside and dedicating their lives to working on the ground to improve rural conditions, not through regulations issued in Cairo” (Fathy, 2000).

New Bariz Village, 1967. The village consists of a wide site including market, workshops, brick factory, public spaces (coffee houses, mosques, libraries, etc.) as well as official buildings such as executive offices and residences.

New Bariz Village. While designing the village, Hassan Fathy visited the neighbouring villages of the old Kharga near the site and analysed the traditional building types. He adapted these structural details according to the current needs and designed the project.

New Bariz Village

Turgut Cansever, who relates the phrase "There are two pearls of wisdom that the last prophet added to the previous ones: the sublimity of Individuality and the love of Beauty" to the architectural context (Doğan, 2015), says the following on this subject: "The engineering of the 19th century changed the world, and this change occurred in the form of complete destruction of culture. What an individual produces is shaped by the reflection of their thoughts and beliefs on what they do. In other words, there is an inseparable bond, a unity between form and belief. When you think that something produced by technology is a solution on its own, it is also a belief. Still, it also means that the existence of human beings, human cognition and reality are pushed aside, and a single factor alone determines human behaviour, which deifies technology. In this sense, technology is an entity that cannot look at the world holistically and creates one-dimensional products without understanding the world in its entirety. It fulfils the needs of the biological existence of human beings. But which of the social needs of human beings does it fulfil? For example, when you build a thirty-storey building and place a family there, it means that you dictate to those people where to live. Therefore, you remove those people’s right to create, perceive, evaluate and change their environment" (Cansever, 2010). In modern architecture, the person for whom a space is designed is not specific and defined. In this context, we see that Hassan Fathy architecture follows an inductive method rather than a deductive attitude imposed by modernity and prioritises the preferences and needs of those who will use that space.

Andreoli House in Fayyum. It is one example where he successfully transformed a traditional form into a contemporary one.

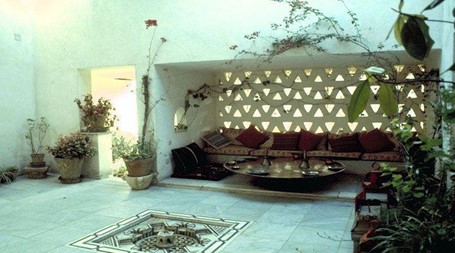

The inner courtyard space of a personalised residence he designed, one of the examples with traditional decorative and structural elements.

Akil Sami House. The principles common to Fathy’s every project are to evaluate the settlement in harmony with the land and the landscape and to aestheticise the different heights required by the building, using traditional elements.

Furthermore, the principle of unity, namely tawheed, is the main point that Islamic architecture is not aligned with modernity. Hence, form and function should not be separated; preserving the unity between them is essential. Oleg Grabar, who raises the question of what makes monuments Islamic except for the way they are used, says: "The existence of the order of meaning in the evolution of Islamic architecture is neither in the forms used, nor in the functions, nor in the vocabulary used to describe form and function, but in the nature of the relationship between these three" (Leaman, 2012). The most basic approach in Hassan Fathy's architecture is to pave the way for ensuring the unity of these three elements in each of his projects rather than creating an architectural type. In addition, another topic related to the disruption of the principle of unity in modern architecture is the design process of the interior and exterior spaces, and gardens by other specialists. Fathy also seeks to ensure harmony in architecture in this regard and designs holistically.

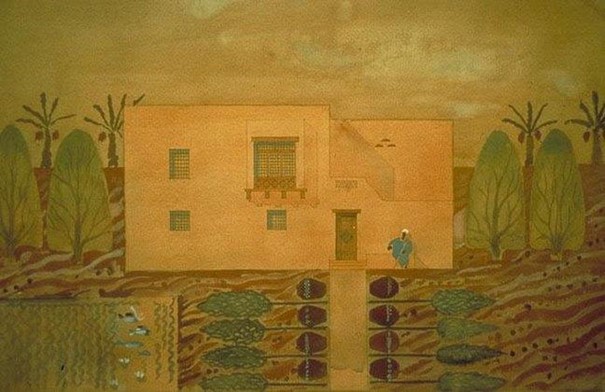

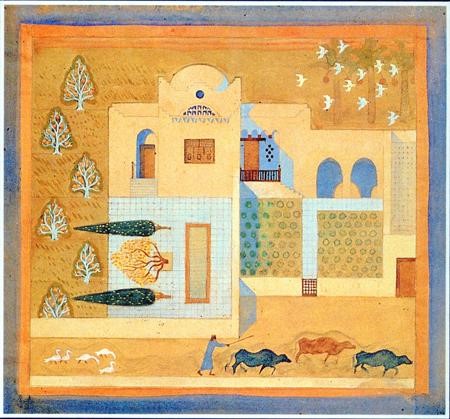

The Drawing of İsmail Abderrazik’s House. The use of miniature techniques to present his project hints at traditionalism. At the same time, in this expression, we also see that he not only evaluates the house as a structural shell but also designs the project through a holistic perspective aligned with its nature.

Fathy encountered many difficulties throughout his life and travelled to Greece to work with Constantinos Doxiadis for a while. They worked together on housing projects in Pakistan and Iraq and a research project on “the city of the future”. After this busy process, he worked on theorising his ideas. After returning to Egypt, the architect opened the doors of his house to anyone interested and became a source of inspiration for many other architects. As an architect known for his contemporary Islamic buildings and discourses, Abdel Wahid al-Waqil was also one of his students. Thus, he also served as a bridge in creating his own aesthetic. Fathy's most well-known project is the New Gourna Village Project, although it was not completed for a number of reasons.

The Drawings of the New Gurna Village Project. The fact that he uses the principles of modern technical painting and presents them integrated with miniature techniques can seen as a projection of his effort to make tradition sustainable without traditionalism. Moreover, one of his main approaches is evaluating the interior and exterior spaces together and incorporating the existing life into his design.

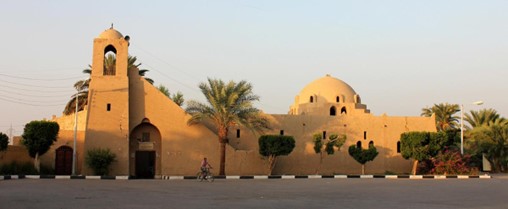

New Gurna Village Mosque. His habit of designing his projects "in alliance with the place" rather than "despite the place" can be analysed even in his relationship with the landscape.

The building is a source reflecting Fathy's thought, experience and spirit. With this project, he won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1980 and the International Union of Architects gold medal in 1984. It inspired many local architectural traditions. The architect, who served on the board of directors of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture for a while, founded the International Institute for Appropriate Technology in Cairo in 1981. Having designed more than 170 projects, Fathy continued his honourable stance and ideas against modernism in many forms and died in Cairo in 1989.

According to Cansever, sacred art seeks beauty in simplicity. It emphasises the mortality of human beings and consists of cheerful modest design and ornamentation, the truth of stone and mortar and their relationship, and the usefulness and practicality of the work of art. Considering these points, it would not be an exaggeration to say that Hassan Fathy's architecture captured this truth.

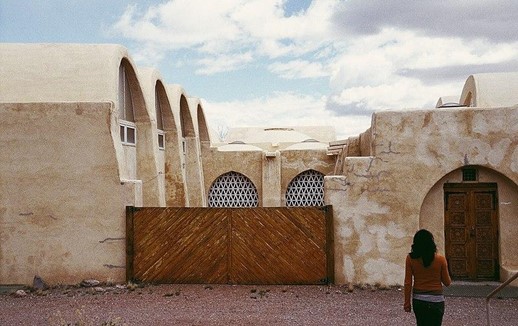

Dar al-Islam Mosque, New Mexico

The architect Abdul Wahid al-Waqil’s phrase, "Tradition is the living spirit of the dead, and traditionalism is the dead spirit of the living", also reflects Hassan Fathy. He was an architect who responded to the needs of his time without resorting to traditionalism, and was able to pass down his tradition to younger generations.

References

Cansever, T. (2010). Kubbeyi yere koymamak. İstanbul: Timaş Publishing.

Çağdaş Dünya Mimarları Dizisi 5. Hasan Fethi. İstanbul: Boyut Publishing.

Doğan, A. C. (2015). Bir şehir kurmak: Turgut Cansever'le konuşmalar. İstanbul: Klasik Publishing.

Leaman, O. (2012). İslam estetiğine giriş. İstanbul: Küre Publishing.

Nasr, S. H. (2009). Modern dünyada geleneksel İslam. İstanbul: İnsan Publishing.

Ökten, S. (2014). Fincanımda kola var. İstanbul: Tuti Book.

Elif Merve Gürer

Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi Mimarlık Fakültesi mezunu olan Elif Merve Gürer, özel sektörde çeşitli projelerde ve çalışmalarda yer aldı, farklı kurumlarda ders yürütücülüğü yaptı. Şu an mimar olarak mesleğini sürdürmektedir....

Elif Merve Gürer

Elif Merve Gürer