The interconnected ecological destruction in Palestine and South Lebanon highlights the insidious nature of settler-colonialism. By targeting land, agriculture, and water resources, these actions undermine communities. A collective push for environmental justice and decolonization is essential to restore both the land and the cultural ties that sustain it.

The Border Bleeds Green: Ecologies of Ruin and Resistance

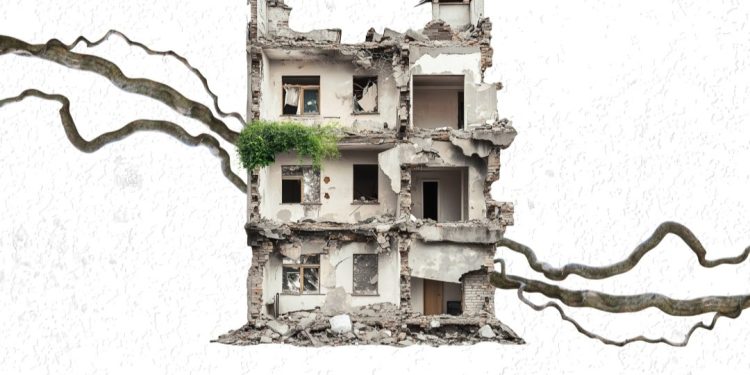

Environmental destruction is not a byproduct of occupation—it is central to the settler-colonial project. In both Palestine and South Lebanon, Israeli military strategies have reshaped the environment to assert control, disable livelihoods, and sever Indigenous ties to land. Through contamination, infrastructural sabotage, and ecological transformation, settler power embeds itself in soil, water, and atmosphere.[1]

This paper conceptualizes ecological violence as settler infrastructure—a system that renders land uninhabitable or repurposed for colonial aims. Rather than treating environmental crises in Lebanon and Palestine as separate, it frames them within a unified, transboundary settler-colonial logic.

Drawing on cases such as the Jiyeh oil spill (Abdallah, 2008), white phosphorus attacks[2], and cluster munition contamination[3], the paper explores how ecological destruction operates politically. It also highlights grassroots resistance, calling for a regional environmental justice framework rooted in decolonization and ecological renewal.

Toxic Warfare and the Materiality of Occupation

Settler-colonialism operates not only through land seizure but through the toxic transformation of the environment. In South Lebanon and occupied Palestine, military operations leave enduring chemical, biological, and infrastructural damage—calculated interventions meant to render landscapes hazardous and agriculturally sterile (Wolfe, 2006; Cavanagh & Veracini, 2016).

In July 2006, Israel’s bombing of Lebanon’s Jiyeh power plant spilled 15,000 tonnes of fuel oil into the Mediterranean—the worst oil spill in the sea’s history, according to the UN

In July 2006, Israel’s bombing of Lebanon’s Jiyeh power plant spilled 15,000 tonnes of fuel oil into the Mediterranean—the worst oil spill in the sea’s history, according to the UN (Abdallah, 2008).The slick polluted over a third of Lebanon’s coast and reached Syrian and Cypriot waters. AUB researchers documented lingering PAH contamination in marine life. This mirrors attacks on Gaza’s water and fuel infrastructure, where repeated bombings have collapsed sanitation systems (Abdallah, 2008).

White phosphorus has been used over civilian areas in both Gaza and South Lebanon, incinerating farmland and causing respiratory injuries.[4] In Aita Shaab and Kafr Kila, Lebanese farmers report poisoned soil and dead livestock. Gaza faces parallel contamination amid collapsed sewage networks.

Cluster munitions further this toxic warfare. In South Lebanon, over one million unexploded submunitions remain buried in agricultural land, introducing heavy metals into soil and threatening food systems.[5] Gaza faces similar risks, though data remains limited.

This environmental degradation exemplifies Nixon’s (2011) “slow violence”—a lingering, cumulative assault that rewrites survival itself. Settler-colonialism displaces not only people, but ecologies, by poisoning the land.

Erasing Agrarian Lifeworlds: Uprooting Land and Labor

At the heart of settler-colonial strategy lies not only territorial conquest, but the erasure of agrarian lifeworlds—the deep, intergenerational ties between people, soil, and seasonal labor that sustain livelihood and cultural identity. In both occupied Palestine and South Lebanon, agricultural destruction is deliberately timed, spatially targeted, and symbolically charged (Campbell, 2020; Huambachano, 2019).

In Palestine, over 800,000 olive trees have been uprooted since 1967, many near settlements or behind the separation wall.

In Palestine, over 800,000 olive trees have been uprooted since 1967, many near settlements or behind the separation wall.[6] These groves support over 100,000 families and serve as cultural anchors. Their destruction is both economic sabotage and an assault on ancestral memory (Simaan, 2017; Braverman, 2009). Irrigation systems, terraced fields, and seed banks have also been disrupted, fragmenting the agroecological knowledge that sustains rural life (Sansour, 2023; Abu Awwad, 2016).

South Lebanon has faced parallel attacks. In Khiam and Marjayoun, white phosphorus and cluster bombs have scorched farmlands.[7] Tobacco fields in Aytaroun, citrus in Tyre, and vines near Blida have been bombed or abandoned due to contamination. Notably, assaults have coincided with harvest seasons—in 2006 and again in 2023–2024—disrupting critical cycles of collection.

This targeting of agriculture reflects a colonial logic: to unroot people by destroying what binds them to place. Farming becomes a frontline of resistance. When seeds, soil, and harvests are lost, it is not only food that disappears—but sovereignty, endurance, and identity.

Water as a Tool of Territorial Engineering

Control over water is a key strategy of settler-colonial governance, enabling both resource domination and the redrawing of sovereignty (Selby, 2013; Alatout, 2008). In Palestine and South Lebanon, water systems have been deliberately targeted, restricted, or reengineered to support asymmetrical power structures. Far from neutral, water flows have been manipulated to fragment Indigenous territorial continuity and deepen dependency.

In the occupied Palestinian territories, Israel’s dominance over key water sources—particularly the Mountain Aquifer and Jordan River—has constrained Palestinian access to potable water, irrigation, and agricultural viability.[8][9] Through the Joint Water Committee and military regulations, Palestinians are often denied permits to dig wells or repair cisterns, while settlements expand water-intensive agriculture (Selby, 2013). As a result, per capita Palestinian water consumption often falls below WHO minimums, especially in Area C of the West Bank and Gaza.[10] In Gaza, repeated bombings of sewage and desalination plants have collapsed the region’s hydrological infrastructure, leaving over 95% of groundwater undrinkable.[11]

South Lebanon, though not under formal occupation, has experienced targeted bombardment of water-related infrastructure—most notably the Wazzani Springs and Litani River basin. Pumping stations in Aytaroun and Blida were disabled during the 2006 war and again in 2023, causing severe shortages during key agricultural periods.

Water, like land, has become a battleground. Its control restricts mobility, undermines agriculture, and reinforces settler-colonial aims. Hydrological sovereignty is thus not only about access—but about survival, rootedness, and resistance (Alatou, 2008; Nixon, 20011).

Border Ecologies: The Lebanon–Palestine Frontier as a Zone of Shared Ruin

Borders in settler-colonial geographies function as tools of spatial and ecological fragmentation (Razac, 2000). The Lebanon–Palestine border exemplifies this, forming an “ecological bifurcation zone” where Israeli environmental warfare intersects across Aytaroun, Blida, and Houla. Lebanese villages face bombardment and toxic munitions (Khayyat, 2022), while across the border, Palestinian lands are replaced with afforestation and militarized greenbelts (Forman & Kedar, 2004), reflecting parallel logics of dispossession and control.

For instance, Maroun El Ras lies directly opposite the settlement of Avivim. Its agricultural terraces have been scorched by war, while Avivim has expanded through state-subsidized afforestation (Peluso & Vandergeest, 2011). This bifurcation of ecological futures—one toward rootedness, the other toward erasure—reflects how settler-colonialism manipulates both land and time (Yacobi, 2009).

Beyond Maroun El Ras, the Blue Line is fractured by blast zones and UXO perimeters, disrupting ecological flows like watershed and seed dispersal (Zurayk, 2020; Khayyat, 2022). The Lebanon–Palestine frontier thus becomes a living archive of environmental partition and resistance (Molavi, 2023). Healing demands a shared ecological vision, where resistance rejects imposed divisions and reconnects people to land across borders.

Resistance Through Soil and Seed: Grassroots Environmental Recovery

In the face of ecological destruction, resistance takes root not only in protest or litigation but in the quiet, persistent labor of restoring land. Across both South Lebanon and Palestine, grassroots actors—farmers, scientists, cooperatives, and youth collectives—are reclaiming contaminated landscapes through what might be called ecological counterinsurgency: the deliberate reparation of soil, seed, and community infrastructure in defiance of settler-colonial degradation (Khayyat, 2022).

In South Lebanon, organizations such as university-led labs—particularly at the American University of Beirut—have initiated soil testing, heavy metal detection, and seed viability studies across impacted border villages (Karnib & Faraj, 2024). In Shamaa, community-led mapping and crop rotation are enabling cautious cultivation in phosphorus- and UXO-contaminated fields. In Ainata, the women-led Dalla project integrates composting, seed saving, and community kitchens, turning agroecology into a tool for healing and autonomy.

In Gaza, where buffer zones and contamination restrict farmland access, residents have transformed rooftops into growing spaces. Urban farms, hydroponics, and water harvesting systems are led by youth and women’s initiatives (Molavi, 2023). Local seed banks reduce dependency on Israeli agricultural inputs and preserve plant diversity. [12]These projects transform vertical surfaces into productive land, defying the settler-colonial logic of spatial enclosure and economic dependency (Molavi, 2023).

These practices reflect antifragility—the ability to grow stronger under pressure. By enriching soil and community ties, they reimagine land not as a battlefield, but as a living archive of memory and resistance (Davis & Burke, 2011). They also challenge top-down humanitarian models, privileging intergenerational knowledge and spiritual ties to land. In this vision, seed becomes a vessel of continuity—linking ancestors to descendants, and loss to renewal (Kimmerer, 2013).

Conclusion

Ecological destruction is not incidental but central to settler-colonial strategy. In Palestine and South Lebanon, Israeli military and territorial practices have weaponized the environment—contaminating soil, destroying agriculture, and severing Indigenous ties to land. From Jiyeh’s oil spill to Gaza’s scorched fields, landscapes become battlefields where sovereignty is erased. This paper has shown that such violence forms a coherent, transboundary project. Through water control, toxic warfare, and agricultural disruption, Israeli policies extend domination into the biosphere. The Lebanon–Palestine border is not a buffer, but a shared geography of ruin—where settler-colonialism operates across different legal contexts toward the same end.

References

[1] See https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/environmental-update-no-03-lebanon-crisis-24-aug-2006

[2]See https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/06/05/lebanon-israels-white-phosphorous-use-risks-civilian-harm

[3] See https://www.clusterconvention.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Report-LandmineAct-EconomicImpactClusterMunitions-June2008.pdf

[6] See IMEU. (2022). Fact sheet: Israel’s environmental apartheid in Palestine. https://imeu.org/article/environmental-apartheid-in-palestine

[7] See https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/06/05/lebanon-israels-white-phosphorous-use-risks-civilian-harm

[8] See https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/775491468139782240/west-bank-and-gaza-assessment-of-restrictions-on-palestinian-water-sector-development

[9] See https://www.unescwa.org/news/escwa-launches-report-israeli-practices-towards-palestinian-people-and-question-apartheid

[10] See. https://www.amnesty.eu/news/troubled-waters-palestinians-denied-fair-access-to-water/

[11] See https://www.ochaopt.org/publications/fact-sheets?page=7

[12] See. https://agroecologyfund.org/nurturing-seeds-of-freedom-in-palestine/

Abdallah, R. A. A. (2008). Environmental impacts of Jiyeh oil spill (PhD thesis, American University of Beirut).

Nida Abu Awwad. (2016). Gender and Settler Colonialism in Palestinian Agriculture: Structural

Transformations. Arab Studies Quarterly, 38(3). https://doi.org/10.13169/arabstudquar.38.3.0540

Alatout, S. (2008). States of scarcity: Water, space, and identity politics in Israel, 1948–59. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26(6), 959–982.

Selby, J. (2013). Cooperation, domination and colonisation: The Israeli-Palestinian Joint Water Committee. Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem. https://www.arij.org/publications/papers-reports/2013-papers-reports/cooperation-domination-and-colonisation-the-israeli-palestinian-joint-water-committee/

B’Tselem. (2023). Parched: Israel’s policy of water deprivation in the West Bank. https://www.btselem.org/publications/summaries/202306_parched

Braverman, I. (2009). Uprooting identities: The regulation of olive trees in the occupied West Bank. Political and Legal Anthropology Review, 32(2), 237–264.

Campbell, H. (2020). Farming inside invisible worlds: Modernist agriculture and its consequences. Bloomsbury Academic.

Cavanagh, E., & Veracini, L. (2016). The Routledge handbook of the history of settler colonialism. Routledge.

Davis, D. K., & Burke, E. (Eds.). (2011). Environmental Imaginaries of the Middle East and North Africa. Ohio University Press.

Forman, G., & Kedar, A. (2004). From Arab land to ‘Israel lands’: The legal dispossession of the Palestinians displaced by Israel in the wake of 1948. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 22(6), 809–830.

Huambachano, M. (2019). Indigenous food sovereignty: Reclaiming food as sacred medicine in Aotearoa New Zealand and Peru. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 43(3).

Karnib, M. Y., & Faraj, M. K. (2024). Qualitative method for White Phosphorus detection in South Lebanon soils. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2857, Article 012034.

Khayyat, M. (2022). A Landscape of War: Ecologies of Resistance and Survival in South Lebanon. University of California Press.

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions.

Molavi, S. (2023). Environmental Warfare in Gaza: Colonial Violence and New Landscapes of Resistance. Manchester University Press.

Nixon, R. (2011). Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Harvard University Press.

Peluso, N. L., & Vandergeest, P. (2011). Political ecologies of war and forests: Counterinsurgencies and the making of national natures. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 101(3), 587–608.

Razac, O. (2000). Barbed Wire: A Political History (pp. 15–28). New Press.

Lee, S. (2023). Vivien Sansour plants seeds of hope for Palestine. Asian American Arts Alliance. https://www.aaartsalliance.org/magazine/stories/palestinian-artist-vivien-sansour-plants-seeds-of-hope

Selby, J. (2013). Cooperation, domination and colonisation: The Israeli-Palestinian Joint Water Committee. Water Alternatives, 6(1), 1–24.

Simaan, J. (2017). Olive growing in Palestine: A decolonial ethnographic study of collective daily-forms-of-resistance. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14427591.2017.1378119

Wolfe, P. (2006). Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research, 8(4), 387–409.

Yacobi, H. (2009). The Jewish-Arab City: Spatio-politics in a Mixed Community. Routledge.

Zurayk, R. (2011). Food, farming, and freedom: Sowing the Arab Spring. Just World Books.