Book Review: Regarding the Pain of Others

Susan Sontag. Regarding the Pain of Others. Picador, 2004.

One of the 20th century's most influential intellectuals, Susan Sontag, is a Jewish-American human rights activist, writer, photographer, and documentary filmmaker. She is a thinker whose world of thought has been shaped by the power of photography. Among Sontag's best-known works are Against Interpretation, a collection of essays, and On Photography, which have had a significant impact by addressing the societal and cultural influences of photography. Other important works by Sontag include Illness as Metaphor and Regarding the Pain of Others, which Sontag wrote to seek answers to the questions regarding the use of images, the way violence is reflected, the concern to aestheticize pain, the normality of the process of getting used to and adapting to stimuli, the banalization of war images and how this will affect contemporary society.

In this book, Susan Sontag answers the question "How, in your opinion, are we to prevent war?" posed to Virginia Woolf by a royal legal advisor living in London. From a feminist point of view, Woolf responds that war is a "man's game" (Sontag, 2003, p. 16) and criticizes the elitist attitude of the advisor. Sontag's response centers on the agreement about whether war should continue or cease. She stresses the importance of recognizing it as an inherent aspect of human nature, which should be universally condemned and detested by all. Instead of approaching it from a gendered perspective of "us vs. them," it should be regarded as a repugnant phenomenon that goes against our shared humanity. Furthermore, when it comes to discussing photography as evidence of war, there is an undeniable effort to persuade the privileged masses, who do not directly experience the atrocities in such "barbaric" situations anywhere in the world, to stand on the right side that war is something terrible and should be stopped. Sontag insists on the necessity of common values that unite all humanity regarding the suffering of the other.

In this book, Sontag considers the tendency to remain silent while seeing others suffer as a product of the modern era; however, she does not find it ethical. She critically emphasizes the tendency to turn war images into spectacles, silence the masses, and normalize killing. The juxtaposition of the moment of death of a republican soldier published in Life magazine with a mannequin with slicked-back hair creates a contradiction and evokes a sense of mockery of human emotions and the impression that the event is fake. Therefore, the sincerity of the noble act of the war photographer, aiming to mobilize the audience at the risk of injury, should be questioned.

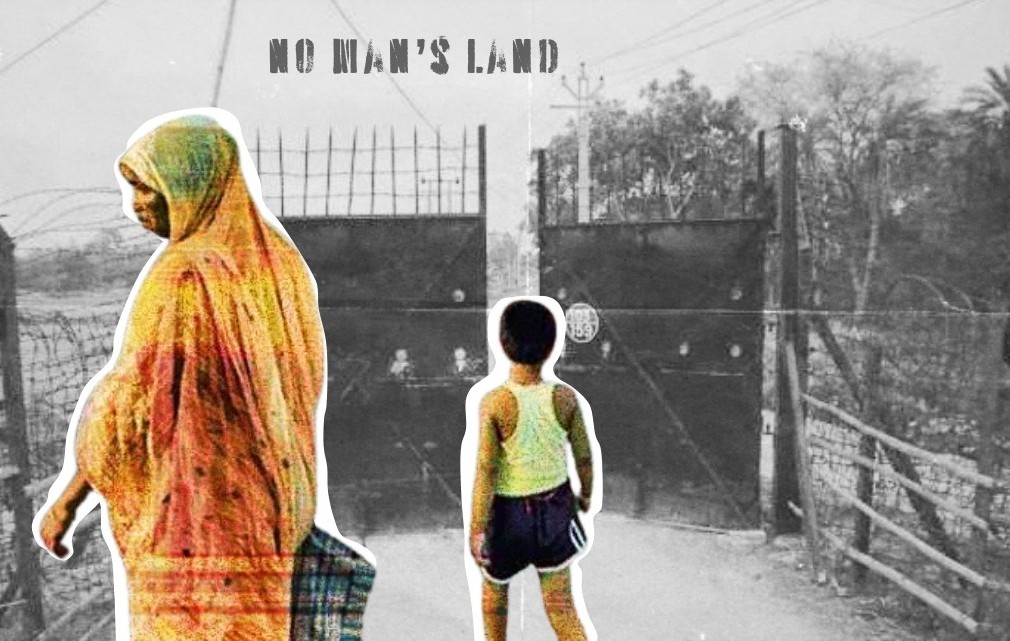

Since October 7, the images we encounter in the media regarding the Palestinian genocide have been characterized by Palestinians who express pity not for themselves but for the silent bearers of conscience, whom we can refer to as the "other," i.e., the Muslim viewers who are not exposed to the war. This portrayal fails to evoke the expected remorse among the Muslim audience due to the long period of war, with the images presented pushing the limits of the pain threshold quite intensively. It should be noted that the object used in the presented content is not a mere commodity. Since the object used in the videos presented as social media content is people with flesh and blood, strategies that will trivialize the issue should be avoided.

Since the object used in the videos presented as social media content is people with flesh and blood, strategies that will trivialize the issue should be avoided.

Sontag has noted that an image could serve as a call for peace as well as a cry for revenge (Sontag, 2003, p. 22). In a photograph featured on the cover of The New York Times on November 13, 2001, the terrifying stare of a Taliban soldier is presented, which serves to reduce the viewer to a voyeuristic position. Such photographs could effectively confront the viewer with the horrors of war, yet sometimes, they may also evoke a desire for war to continue. Palestinians, who embrace death as a blessing because of their religion, may cause the "other" watching the war from afar to prefer fleeing rather than remaining a mere spectator to the ongoing massacre because of the discomfort caused by prolonged inaction in individuals exposed to intense pain. Choosing not to look at the images of human bodies buried under rubble, as Sontag reminds us, might be a measure to prevent a sense of hopelessness from being triggered. It should be unsettling to entertain the idea of an imaginary bond between them and us as voyeurs. Not wanting to expose oneself to intense pain and lead oneself to inertia, it may be preferable not to be alone with intense pain in the face of what is seen. Otherwise, by remaining silent and not finding the strength to speak out for Palestine, even the slightest possible resistance could be lost.

Choosing not to look at the images of human bodies buried under rubble, as Sontag reminds us, might be a measure to prevent a sense of hopelessness from being triggered.

As Sontag questioned in her essay "Regarding the Torture of Others," how can someone grin at the sufferings and humiliation of another human being? (Sontag, 2004, p. 3) They can do so if they believe the "other" belongs to a race or religion inferior to their own. As Berger also argues, the discontinuity of moments of agony recorded by the photographs will make the individual feel morally inadequate over time (Berger, 2014, p. 51). The sudden effect exerted on the viewer by the photograph renders them powerless and immobilized in the wake of violence. I believe that the insensitive display of the images of torture cannot extend beyond turning the victim of violence into a commodity. Although it may not condone torture and murder, it will lead the viewers to remain silent and will not elevate them beyond the position of a voyeur eager to witness the barbarity.

Towards the last chapters, Sontag questions whether a war can be stopped with just a handful of photographs. They certainly cannot end a war, but it might be the last resort to evoke compassion in the "other" against the endless injustice in the world. Because the sensitivity to prompt action can only be created by regarding the pain of others. She also provides examples of war photographers such as Robert Capa, who became famous during World War I. This could be seen as a threshold in the legitimacy of newspaper photography in 1940. The earnings of the photographers are positively affected by the working conditions and the fact that their point of view can expose the war.

They certainly cannot end a war, but it might be the last resort to evoke compassion in the "other" against the endless injustice in the world.

We can argue that war correspondents censor the atrocities by designing the shooting scenes to dramatize the message they want to give in their photographs. In this sense, in its hegemonic form, a photograph loses its credibility to demonstrate reality; therefore, we should not overlook the danger of war photography becoming a profession profiting from human suffering. Even such an implication is quite humiliating for the work and the person doing it, and it requires the artist to act very sensitively.

Approaching a war photograph purely from an artistic perspective is also a shameful act. Making art out of others' pain can be interpreted as belittling and disrespectful towards the agony of the afflicted. Being unable to view reality as it is and trying to shape it deliberately for individualistic aesthetic concerns is injurious to human dignity. The effort to create art will lead to a distracting, reality-distorting effect. In this sense, I agree with Sontag's view of the "inauthenticity of the beautiful" (Sontag, 2003, p. 83). I believe that war photography should not be left in the hands of art ideologues but should be regarded as a valuable profession providing evidence, confirming facts, and having a critical role. Reflecting reality as it is without manipulating it or romanticizing it, without embellishing the work, is more valuable. It is painful to look at such heartbreaking photographs, but the only element that will affect people and make them take action is the shock effect. Otherwise, I do not think a pain that does not mobilize people can lead to change.

In conclusion, I believe what Sontag meant by regarding the pain of others aligns with the purpose of writing this book. The fact that such a book was written by a female activist who courageously dared to be amid the agony without cowardice has influenced my understanding of her ideas. We can say that the way we see the photograph, which is used as a tool in the service of pain, undermines our perception of reality and, while aiming to convey the pain of foreign people, may ironically distance the recipient from the pain. Therefore, aestheticizing pain to have an impact and enable the viewer to take action against the injustice should be severely restricted, ensuring that it does not obscure reality or pay no heed to its immorality. In other words, the images should not become ordinary, and intense emotions should not be normalized by being adapted to them gradually.

References

Berger, J. (2014). “Photographs of agony” In Understanding a photograph. Metis Publications. 49-52.

Medyascope plus, Harikalar Odası – Susan Sontag: Camp ve Otesi (Sep 27, 2020). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bRJj-nD8_Ks

Sontag, S. (2003). Regarding the pain of others. Istanbul: Can Publications.

Sontag, S. (2004). Regarding the torture of others: New York Times Magazine. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/23/magazine/regarding-the-torture-of-others.html?pagewanted=print&src=pm

Elif Akkuş

Elif Akkuş. İstanbul Medeniyet Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Sosyoloji Bölümünden 2022 yılında mezun oldu. İLKE Vakfı bünyesindeki Sivil Toplum Akademisinde araştırma asistanı olarak görev almaktadır....

Elif Akkuş

Elif Akkuş