The Underrepresentation of Uyghurs in the Age of Social Media is Rooted in Settler Colonialism

In the late 1940s, three enduring occupations began in three distinct parts of the world, marking a new wave of colonization as European colonialism was coming to an end. India occupied Kashmir in 1947, Israel began its occupation of Palestine in 1948, and China occupied East Turkestan in 1949 (the preferred term for the Uyghur homeland in Eastern China - “Xinjiang,” a Chinese name which means “New Frontier” erasing Uyghur and other Turkic people’s long presence in the region). This temporal proximity is not merely coincidental; it represents a historical moment when one form of colonialism was waning and another was emerging. The occupiers, some of whom saw themselves as formerly oppressed, utilized similar justifications for their colonial endeavors, leading to a continuum of settler colonialism.

Patrick Wolfe, a leading scholar on settler colonialism, describes settler colonialism as an ongoing mechanism rather than a historical event, aiming to erase indigenous populations to facilitate settler expropriation of land. Wolfe famously noted, “Settler colonialism destroys to replace” (Wolfe, 2006, p. 388). Over seven decades in Kashmir, Palestine, and East Turkestan, the settler powers have systematically worked to obliterate existing cultures, languages, and forms of resistance, replacing them with fabricated narratives of prosperity—what I refer to in my research as “Digital Potemkin Villages.”* These digital façades obscure the absence of indigenous voices, which have been silenced and replaced with narratives more palatable to the colonizers.

The suppression of Uyghur voices and the proliferation of Digital Potemkin Villages underscore the ongoing struggle for truth, liberation, and justice in the face of the oppressive Chinese regime.

The underrepresentation of Uyghurs in the media is a profound issue, intricately tied to the mechanisms of settler colonialism. By examining the roles of social media influencers in constructing distorted representations of occupied regions, we gain insight into the broader strategies of narrative control employed by settler governments. The suppression of Uyghur voices and the proliferation of Digital Potemkin Villages underscore the ongoing struggle for truth, liberation, and justice in the face of the oppressive Chinese regime. As digital platforms continue to shape public perceptions, it is crucial to critically analyze and challenge the narratives that seek to obscure the lived realities of oppressed communities. In my Ph.D. research, I study how Muslim minority dissidents' voices are silenced on social media platforms and how oppressive regimes use different methods and tools to fill that void with propaganda. One such tool is social media influencers. In an era dominated by social media, the battle for narrative control has intensified. Influencers, particularly those aligned with pro-government agendas, play a crucial role in shaping perceptions of occupied territories. Pro-government influencers are adept at manipulating social media to project an image of normalcy in occupied regions. For example, you will find countless vlogs of Chinese influencers on YouTube that showcase the “bright” side of East Turkestan, focusing on food, landscapes, and culture while ignoring the egregious human rights violations, concentration camps, and strict surveillance. These state-sponsored narratives are designed to avoid detection as government propaganda, thus escaping labels like "Chinese government media" on platforms like X and YouTube.

Figure 1. A vlog on YouTube refers to Urumqi and Xinjiang as the "most developed" Muslim cities in the world.

On the other hand, the Chinese government’s strategy also extends beyond national borders, enlisting influencers and journalists of various ethnicities and religions from other countries to create vlogs and media portraying East Turkestan as a region of normalcy. This tactic is particularly effective when influencers and journalists from Muslim-majority countries, such as Pakistan, present a sanitized version of life in East Turkestan, thereby reinforcing the Chinese government’s narrative among global Muslim audiences. This personal connection between influencers and their millions of followers lends an air of authenticity to their content, which overshadows the voices of Uyghur dissidents in the diaspora. Therefore, when a Pakistani Muslim vlogger goes to East Turkestan on the orders of the Chinese government, they say exactly what the rest of the Muslim audience in Pakistan and other parts of the world wants to hear: “There is no religious persecution in East Turkestan.” Their lies display a conviction as if Uyghurs are happily living under Chinese rule and as if East Turkestan is a part of China. But what matters here is how much awareness you already have about the issue. If you have Uyghur friends or have research interests in the region like me, you can easily call off the façade of these social media influencers that try to exonerate China of its crimes in East Turkestan. If you do not, chances are high that you will fall for the lies, sometimes even glossed with labels of extremism and terrorism. The Chinese government has invested heavily in controlling the narrative around the Uyghurs and Xinjiang. Through state-sponsored media and international propaganda efforts, the government presents its actions in Xinjiang as necessary measures against terrorism and extremism.

Figure 2. The tweet by the Global Times, established by the Chinese Communist Party for propaganda, celebrates the success of the fight against terrorism and security measures in the Xinjiang region.

Although the Uyghur diaspora is scattered all around the world, they have faced significant challenges in gaining visibility in global public discourse about human rights violations and ethnic cleansing.

This narrative, propagated through various news and social media channels, aims to counteract international criticism and shape public perception (Blanchard & Ben, 2018). However, if you reside somewhere in North America, there is a high probability that you have never even heard about this Turkic Muslim minority group. Despite being central to major human rights issues, their stories and experiences are often underreported or misrepresented. Although the Uyghur diaspora is scattered all around the world, they have faced significant challenges in gaining visibility in global public discourse about human rights violations and ethnic cleansing.

The Chinese government's stringent control over information and media within its borders significantly hampers the ability of both domestic and international journalists to report on Uyghur issues (Schiavenza, 2019). China has dedicated PR firms in many countries to run their propaganda machinery (Cook, 2023). Independent reporting is often restricted, and journalists face risks of harassment, detention, or expulsion. This creates a challenging environment for uncovering and disseminating information about the Uyghurs. There are two significant points here that I have come to understand through my research and interviews with the Uyghur dissidents in exile. One is erasure, where direct surveillance of Uygur dissidents and journalists on social media platforms prevents them from exposing the actual truth of East Turkestan. The other is the replacement, where the Chinese government spends a lot of resources around their PR campaigns in East Turkestan by inviting vloggers from not only China but also outside countries on tours to this troubled region, portraying a facade of normalcy. The distorted representations created by influencers have significant implications. They obscure the harsh realities of occupation and human rights abuses, fostering ignorance and apathy among global audiences. The comparatively limited reach of Uyghur dissidents, constrained by censorship and lack of resources, exacerbates this issue. The resulting information void is filled by pro-government propaganda, further entrenching the occupier’s narrative. Influencer content often fetishizes Indigenous cultures and lifestyles, presenting an illusion of normalcy that benefits settler governments. This content not only silences dissident narratives but also replaces them with a curated version of reality that conceals the ongoing settler colonialism.

Influencer content often fetishizes Indigenous cultures and lifestyles, presenting an illusion of normalcy that benefits settler governments.

The Uyghurs have a rich history in Central Asia, with their own distinct language, culture, and traditions. Over the centuries, the region known today as Xinjiang (new territory) has been a crucial hub along the Silk Road, fostering a blend of various cultures and religions. In recent decades, however, the Uyghur identity has been increasingly suppressed by the Chinese government. According to Amnesty International's 2021 report on Uyghurs, policies aimed at assimilating Uyghurs into Han Chinese culture, such as restrictions on religious practices, language use, and cultural expressions, have contributed to the erosion of their unique cultural identity. These actions have culminated in reports of severe human rights abuses, including mass detentions in what the Chinese government calls "re-education camps." The underrepresentation of Uyghurs in media is a multifaceted issue with significant implications for global awareness, policy, and the Uyghur community. By understanding the factors contributing to this underrepresentation and actively working to address them, journalists, media organizations, policymakers, and the public can help bring the Uyghur crisis to the forefront of global discourse. Increased media coverage can catalyze international action, support advocacy efforts, and ultimately contribute to justice and relief for the Uyghur people.

*Editor’s Note: The term “Potemkin village” refers to an impressive façade designed to hide or divert attention from an undesirable condition.

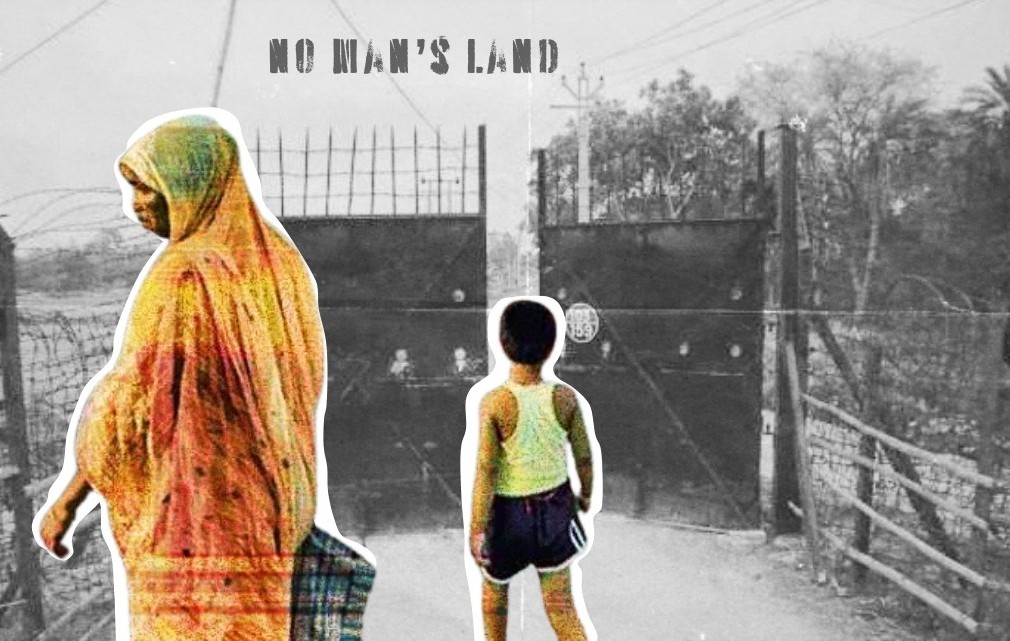

**Editor's Note: The cover is by Er.serhan, Istiqlal Media, https://www.istiqlalhaber.com/page/news/4229

References:

Blanchard, B., & Miles, T. (2018). China mounts publicity campaign to counter criticism on Xinjiang. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN1MC0IL/&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1718122531396533&usg=AOvVaw3K_KHtKKACWO1qQ3KPCZOO

Cook, S. (2023, July 3). China’s foreign PR enablers. The Diplomat. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com

“Like we were enemies in a war.” (2021). Retrieved from https://xinjiang.amnesty.org/

Schiavenza, M. (2019). Why it’s so difficult for journalists to report from Xinjiang. Retrieved from https://asiasociety.org/blog/asia/why-its-so-difficult-journalists-report-xinjiang

Wolfe, P. (2006). Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research, 8(4), 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240

Ifat Gazia

Ifat Gazia is a Kashmiri Muslim scholar currently pursuing her Ph.D. in Communication at UMass Amherst. Her areas of study are Kashmir, Palestine, and East Turkestan and her work broadly looks at the intersection of technology and social justice. Ifa...

Ifat Gazia

Ifat Gazia