Remigration Patterns of Muslim Diasporas in the West: The Case of French Muslims

The 4.7 to 5.1 million French Muslims, according to our estimates (Refas, 2021), have recently developed new migration behaviors that have not been studied in the literature. We observe three patterns mainly: a selective migration to high-income countries (including booming migration flows to GCC countries), a rapidly expanding migration to Türkiye and Malaysia, and a resurgence of migration to former colonies that had previously experienced a consistent reduction in migration flows from France since the 1980s. Overall, more than 140,000 people migrate to Muslim-majority countries from France every year today, and that flow of permanent or temporary migrants offers a wide range of economic potentials that ought to be studied further. The drivers of migration decisions are the main focus of our research.

Going back to history first, note that in the 1970s and 1980s, large cohorts of Muslims from post-independence African countries and Türkiye left their native lands to live in the West. At the time, the typical push and pull factors of labor migration were their main motivation for leaving their homeland, family, and native culture by ferryboat and immersing themselves in a completely foreign environment. In the case of France, this wave of labor migrants was predominantly coming from former North African and Sub-Saharan colonies (e.g., Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Senegal, Cameroon and Mali) with dominant or large Muslim populations. A few years later, thanks to progressive immigration laws, the families of these labor migrants also immigrated under the “regroupement familial,” a right recognized under French law in 1978, and thanks to the birthright (“droit du sol”) which grants French nationality to whoever is born in France since the 16th century, they gave birth to millions of second-generation Muslim migrants who predominantly settled for good in France.

Using recent demographic evidence, we estimate that 45 years later, the Muslim immigrants of first, second, or third generation in France range today between 4.7 to 5.1 million (see Table 1). Due to a range of economic and social factors, we observe a growing trend of migration amongst this population, back to the home country of their parents (return migrations) or, interestingly, to third countries (transnational migrations). We also observe other migration patterns, such as temporary migrations or migration strategies involving two or three countries simultaneously (hybrid migrations).

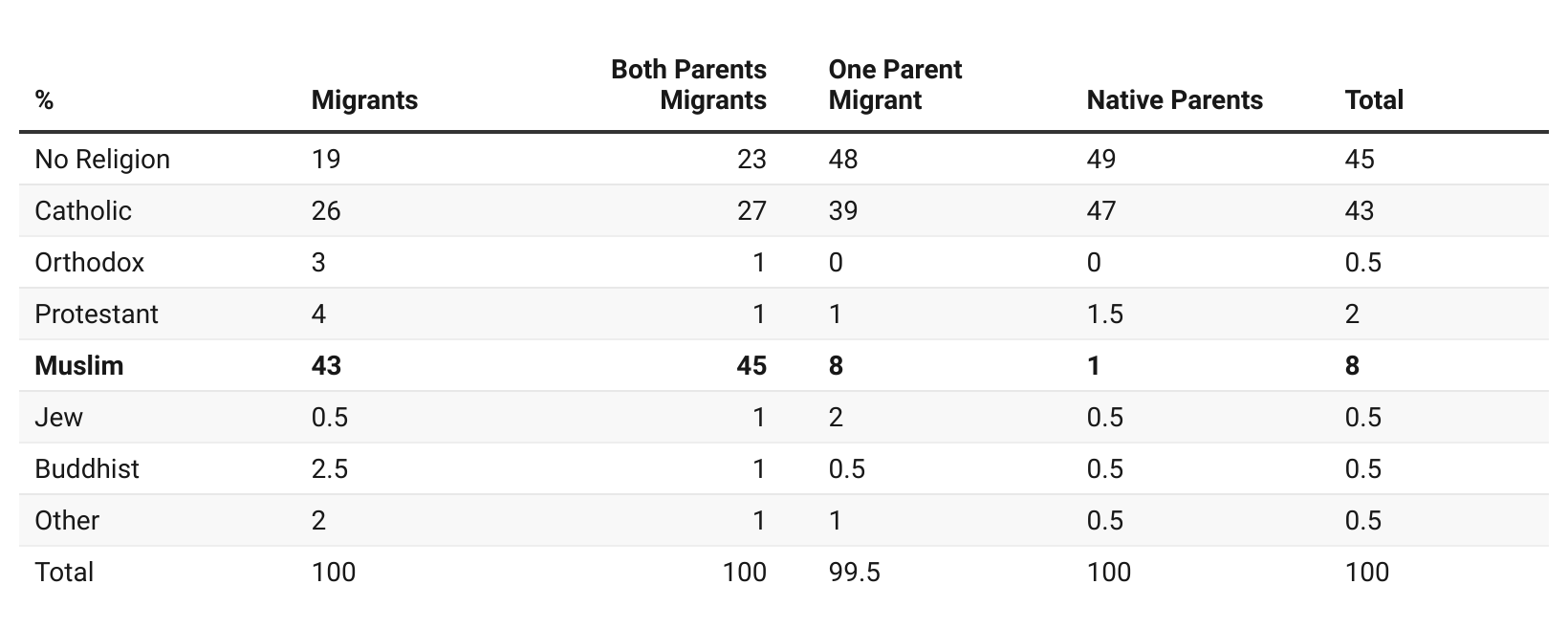

Table 1. Self-declared religious affiliations of migrants and descendants of migrants in France

Source: Trajectoires et Origines 2008, INED

To understand these migration flows, we need to focus on three questions mainly: how these populations have changed over time, in particular in terms of preferences and economic or social behavior (demand-side), how France has changed since the 1970s, and accordingly, if there are new push factors inducing the migration decisions, and how destination countries including homeland of their parents have changed since then and offer new pull factors dragging migration flows.

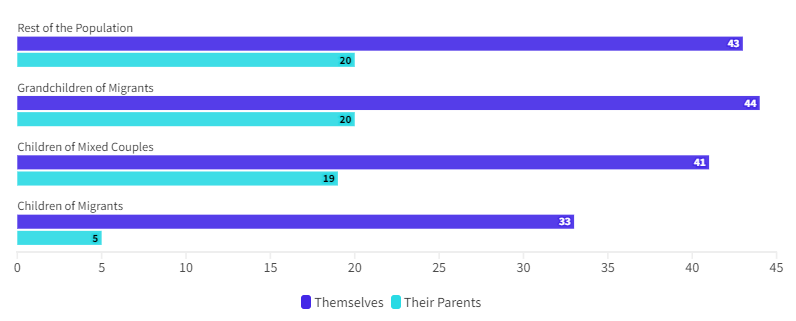

In a nutshell, if we focus on the population of Muslim migrants in France first, we observe that the predominantly blue-collar population that first immigrated to France has put a lot of emphasis on education as a social promotion mechanism, and their progeny is now well-educated and well-inserted in the various social strata of the country (see Figure 1). 33% of the descendants of migrant couples have now graduated with a higher-study degree compared to 5% of their parents (Beauchemin & Simon, 2023). Among second-generation migrants, the proportion is now 44%, i.e., even higher than the rest of the population (43%).

Figure 1. Progression of Higher-Study Graduation Rate Across Generations in France

Source: Trajectoires et Origines 2, INED-INSEE, 2019-2020 (TeO2)

Despite the social recognition and improvements, these populations feel increasingly discriminated against. In 2019-2020, 26% of Maghreb immigrants reported having suffered unequal treatment or discrimination in the last five years (Beauchemin & Simon, 2023). Interestingly, the same data reveals that discrimination linked to origins has, however, decreased due in part to a shift towards religious motive: 11% of people declaring themselves to be religious Muslim women report religious discrimination, compared to 5% ten years ago. Other social issues specific to the context in France affect the migration decisions of these populations. According to the OECD (2022), for example, 34% of the population in France was at risk of depression in 2021, up from less than 10% in 2019, due to a range of factors, including loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite the social recognition and improvements, these populations feel increasingly discriminated against.

On the other hand, the world has changed since the 1970s, and new opportunities for migration have emerged for this population, predominantly French and well-qualified. Classical migration theory predicts that the typical pull factor for a worker is the labor price differential (real or expected) offered for the same profession in destination countries. GCC countries, or other OECD countries, offer such opportunities and, therefore, drag migration flows in line with traditional migration models. However, field observations and structured interviews also indicate that for an increasing number of migrants, despite negative labor price differentials, migration from the West back to the homeland of their parents or to other Muslim countries such as Turkey is a desired option.

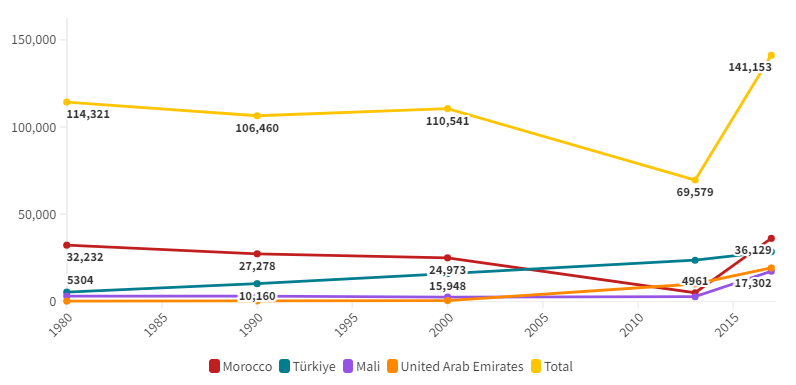

Figure 2 below shows that the total number of migrants from France to Muslim-majority countries has slowly decreased over the period 1980-2013, with a major dip since 2000. But after that, the number of migrants boomed and doubled between 2013 and 2017 for the 16 main destinations of French migrants within Muslim-majority countries. This would strengthen the assumption that due to increased Islamophobia in France and increased religiosity among French Muslims, French Muslims are increasingly looking forward to relocating, generating transnational migration flows that remain to be studied in detail.

The tabulation of recent migration data helps identify some growing trends:

- The massive growth of migration to GCC countries and Malaysia (UAE, Kuwait, Oman, Bahrain, Qatar) with growth from 8 times (Malaysia) to more than 100 times (UAE, Bahrein) in the annual outflow of migrants from France between 1980 and 2017;

- The return to annual volumes is slightly higher than in 1980 for former colonies such as Morocco, Tunisia, or Chad, with the noticeable exception of Algeria, which shows a major reduction in the number of migrants in recent years;

- The massive growth of Turkey as a destination for French migrants, with 28,507 migrants to Turkey in 2017, i.e., more than 5 times the 1980 number;

- The significant growth in the number of migrants to Morocco since 2013 could be interpreted as a growth in return migrations or a growth in new migrants, especially among retired French citizens and industrial employees.

Figure 2. Total Migration to Muslim Majority Countries and Top 4 2017 Migration Destinations from France, 1980-2017

Source: World Bank

It is worth noting that data limitations do not enable us at this stage to distinguish between Muslim and non-Muslim migrants in the data presented, a caveat that an ongoing statistical exercise is trying to correct.

Overall, the economic implications of the migration trends remain relevant for Muslim populations in France and Europe. In 2017 alone, more than 140,000 French citizens or residents have migrated to 16 Muslim-majority countries that we identify as main destination countries. This figure was up from about 70,000 in 2013. The economic implications of that massive outflow of migrants can be studied from the perspective of the recipient or origin country. Countries such as Morocco, Jordan, and Turkey have developed over the years support programs to facilitate investments and return from their expatriated citizens, but the full economic impact of these investments, in particular the spillover effects on the rest of the economy, are yet to be fully understood.

A simplified evaluation of the economic potential of the remigrations of Muslim diasporas in the West to Muslim-majority countries could be attempted by looking at the average savings of these populations and the related investment capacity. For example, Arrondel and Coffinet (2019) report a median wealth of €113,300 per household in France. The 4.7 - 5.1 million Muslims in France (assuming an average of 2.9 persons by household as reported by INSEE) could have an accumulated wealth of €183 to €203 billion in 2019. If the transnational remigration assumption is confirmed for the majority of the 141,153 annual migrants from France to the Muslim-majority countries reported, the potential repatriation of the savings of these migrants to their new country of residence could reach €5.5 billion on an annual basis (€1.4 billion and €1.1 billion for Morocco and Türkiye alone). Other economic implications include transfer or knowledge through direct investment, entrepreneurship or corporate and academic channels. In 2014, Philippe Legrain published Immigrants: Your Country Needs Them, an excellent book about immigration, showing why Western countries should welcome migrants (Legrain, 2014). Ten years later, we probably now need such a book to discuss why transnational migrants are highly needed in Muslim-majority nations.

References

Arrondel, L., & Coffinet, J. (2019). Le patrimoine et l’endettement des ménages français en 2015. Revue de l'OFCE, (1), 49–75.

Beauchemin, C., Ichou, M. & Simon, P. (2023). Trajectoires et Origines 2019-2020 (TeO2): présentation d’une enquête sur la diversité des populations en France. Population, 78, 11–28. https://doi.org/10.3917/popu.2301.0011

Legrain, P. (2014). Immigrants: Your country needs them. Princeton University Press.

Refas, S. (2022). Transnational economic behavior of Muslim diasporas in the West: The case of French Muslims. Journal of Islamic Economics, 2(1), 24–46.

Source: Reuters

Salim Refas

Salim Refas is an international expert in sustainable development and Islamic finance. His primary research interests are international migration and sustainable development. He worked as a consultant for ADB, the World Bank, and the Islamic Developm...

Salim Refas

Salim Refas