Rituals are not only a preserve of “primitive” societies; their influence has transformed throughout history. While it is possible to talk about sacred or spiritual rituals, secular or even virtual rituals have also emerged in the modern era. Furthermore, each and every popular revolution and resistance has brought out its own rituals, yet what distinguishes contemporary movements is the intersection of social media, ritual, and collective identity. In this article, I will analyze how the videos of the al-Qassam Brigades, the military wing of HAMAS, and Abu Obeida, the spokesman for the brigades, released periodically reproduce social media as a space of resistance and create an atmosphere of ritual in the Durkheimian sense. I will also include tweets and images from the videos released to emphasize the “totemic” nature of the created space both in those videos and on social media.

Although Durkheim examines Australian Aborigines and the totemic religions of “primitive” societies in his work, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, he instrumentalizes the rituals and totems as a means of understanding the human psyche and society. The relationship between symbols and community is mutual; that is to say, while society always generates forms of rituals and totems for social cohesion, “social life is only possible thanks to a vast symbolism” (213), Durkheim argues. The feelings are “spontaneously” transmitted to the symbol that represents it (222). The emotions evoked by the symbol engender a common feeling or experience that leads to a sense of belonging and collective conscience. The rituals, therefore, create a space in defined symbolic boundaries where the symbols and feelings are perpetuated constitutively. Consisting of repetitive practices in a particular time and space with an assembled group, the rituals “release new energies that transform” (222) each member of the group. Nevertheless, even though Durkheim puts emphasis on bodily engagement and sacred symbols, intellectuals such as Erving Goffman and Randall Collins have examined micro-level human interactions such as greetings as everyday rituals. Contributing to the discussion, James W. Carey examined how new forms of communication, i.e., the telegraph at that time, created new ritual acts, which paved the way for modern media rituals.

2021 was a milestone for social media activism in the long history of resistance in Palestine against the Israeli occupation, and the Al-Aqsa flood created another wave of media interest in the Palestinian case.

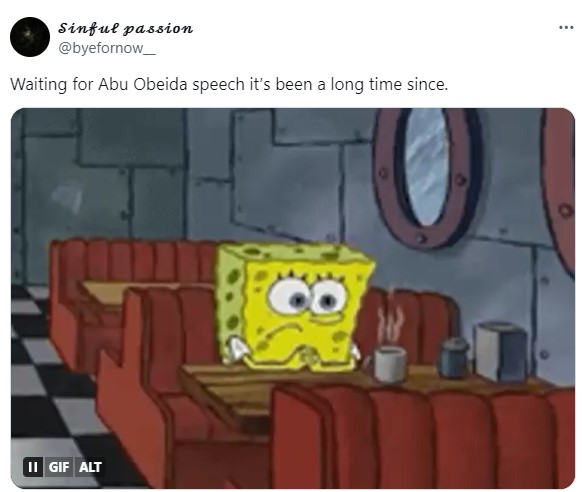

2021 was a milestone for social media activism in the long history of resistance in Palestine against the Israeli occupation, and the Al-Aqsa flood created another wave of media interest in the Palestinian case. While in 2021, individual Palestinians such as Mohammad and Muna al-Kurd siblings came forward, leading to worldwide protests as well as awareness through social media with the hashtag #SaveSheikhJarrah, events unfolding after October 7 put the video releases by al-Qassam Brigades and Abu Obeida forward, reproducing social media as a space of symbols related to Palestinian resistance. The videos are first published on Telegram channels -until the censorship by Telegram in November- every day, after a message that indicates that new videos are coming and that they have launched attacks in specific locations. The videos of Abu Obeida, on the other hand, are published every four to five days. In this sense, the periodic and repetitive release of these videos almost pre-conditions the followers of the case to engage with these videos daily or weekly and creates a heightened emotional state of expectation. For example, one Twitter user mentions how the elderly person in the image waits for Abu Obeida’s videos every day and, most importantly, “listens to [Abu Obeida] while standing,” which reflects the heightened feelings of presumably awe and expectation. The second, on the other hand, shows in a joking manner that the break in the ritualized act of continuous video releases by HAMAS causes another feeling, this time: anxiety.

@ سعد السعيدي, Twitter (https://x.com/salsaeedi/status/1720921320706257284)

“Ebu Ubeyde’nin konuşmasını bekliyorum, son videodan bu yana uzun zaman oldu.” @dearrmarya, Twitter (https://twitter.com/dearrmarya/status/1744432564994015404)

Social media creates a space in which users on social media platforms can share the same emotions and empathize with one another, transcending the limits of proximity or virtuality.

The videos are transferred to bigger social media platforms such as Facebook and, most importantly, Twitter after they are released on Telegram. Therefore, as Durkheim questions, “Repeated everywhere and in every form, how could that image not fail to stand out in the mind with exceptionally sharp relief?” (222), these videos become representatives of the ongoing atrocities. Although the videos are in Arabic and, therefore, fail to generate effect and emotions in the ritualistic space of social media, they are quickly translated into different languages, which restores engagement and creates a social cohesion between those who follow the incidents closely. The moment the videos are released, users create different posts, either praising the acts or condemning them but also turning them into memes, mocking images, as shown in Figure 3. In this sense, besides its use of sharing events, social media creates a space in which users on social media platforms can share the same emotions and empathize with one another, transcending the limits of proximity or virtuality.

I/P Conflict Memes, Quora (https://ipconflictmemes.quora.com/ti-135195543)

For the uninformed or foreign viewer, this image may not be symbolic, but when we analyze the image, these two elements, the red arrow on the tombstone and the man in red head covering, hint at the idea that the symbols are not mere artifices, but instead, they are integral to the representations (Durkheim, 233) and originate outside us. That is to say, when the al-Qassam Brigades release a video, there are certain repetitive elements that distinguish them from the rest of the war videos and create a constitutive relation with the viewer, the red arrows used for pointing the Israeli soldiers or tanks as targets:

AlJazeera Arapça قناة الجزيرة, Youtube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7K3Tg4asQhQ)

But at the same time, for some, these red arrows signify the red triangular shape of the Palestinian flag. Moreover, people put the red arrow shape (🔻) next to their Twitter names. Thus, while creating a collective engagement with the released videos and the ongoing war in Gaza, the symbol also contributes to the collective identity shaped by another symbol, the flag.

On the other hand, wearing a camouflage soldier uniform and a red keffiyeh, Abu Obeida has become the symbol of Palestinian resistance since the 7th of October. Even though keffiyeh is a traditional attire worn in Middle Eastern and Kurdish regions, wearing it in a way that covers the whole face, as worn by the spokesman, has become another symbolic movement that has become inscribed in the symbol itself. Hence, it has also become something durable that is alive not only on social media but also in protests all around the world. Each recorded voice message is shared with the same image, Abu Obeida raising his finger in a threatening manner and the same attire (Figure 5), and this image is being hung as a poster in different countries to display support for HAMAS or becomes a feature in memes as shown in the previous figures.

AlJazeera Arapça قناة الجزيرة

The videos released by the al-Qassam Brigades serve as symbols that create ritualistic spaces on these platforms thanks to the repetitive elements highlighted in them, such as red arrows and Abu Obeida in red keffiyeh.

Therefore, the repeated images and symbols in those videos are utilized in a way that recalls emotions in relation to the resistance even after the videos end. They become durable elements of social life since they are simple and well-defined as well as repeated everywhere on social media.

In conclusion, rituals have transcended the confines of “primitive” societies, and the modern era has witnessed the emergence of virtual rituals on social media platforms. The videos released by the al-Qassam Brigades serve as symbols that create ritualistic spaces on these platforms thanks to the repetitive elements highlighted in them, such as red arrows and Abu Obeida in red keffiyeh. The instant translation of videos into different languages and the reproduction of these videos into memes and other social media posts contribute to a shared experience that transcends physical boundaries. The analysis of these videos, therefore, reveals that these symbolic images not only reflect the Palestinian social resistance but also actively shape the collective consciousness, fostering a sense of identity among those engaged with these contents.

Kaynakça

Durkheim, Émile. “Religion and Ritual.” In Emile Durkheim: Selected Writings, eds by A. Giddens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 219–222

Durkheim, Émile. 1912. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. New York: Free Press

“الجزيرة تبث صورا حصلت عليها لمعارك كتائب القسام والجيش الإسرائيلي شرق غزة.” YouTube, uploaded by AlJazeera Arabic, 11 Dec. 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7K3Tg4asQhQ

I/P Conflict Memes. [Image]. Quora, 12 Dec. 2023. https://ipconflictmemes.quora.com/ti-135195543

سعد السعيدي [salsaeedi] “ينتظر أبو عبيدة كل يوم ولا يستمع إليه إلا واقفاً…” Twitter, 5 November 2023. https://twitter.com/salsaeedi/status/1720921320706257284

🔻[dearrmarya]. “Waiting for Abu Obeida speech it’s been a long time since.” Twitter, 8 January 2024. https://twitter.com/dearrmarya/status/1744432564994015404

Cover source: Getty Images