Invented in the late 19th century, cinema has not been accepted as simply moving photographic images with technological possibilities since the first moment it emerged. As an art form, it has its own linguistic structure. This structure is inherent to modernism and is more inclined to construct global narratives rather than national or regional ones. Hence, since its invention, cinema has traveled across the globe and quickly become an indispensable phenomenon for peoples worldwide. Originated at a time when global trade accelerated as never before, cinema is the product of an era in which not only commercial goods but also ideas and people were on the move. Therefore, regardless of the context in which we consider the concept of migration, it has an equivalent in cinema.

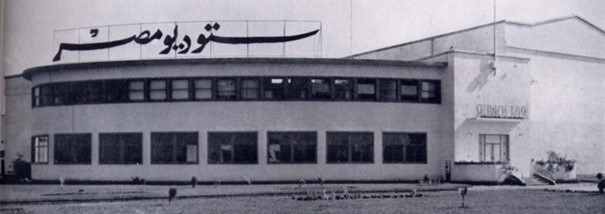

Egypt was the first country among Muslim populations to establish large-scale contact with cinema. The process that began with the construction of large film studios in the 1930s resulted in the establishment of one of the world’s leading film industries. Many immigrant filmmakers contributed to the emergence of Egyptian cinema, which became known as the “Hollywood of the East” (Mejri, 2014, p. 32). Among these filmmakers were Turks like Vedat Örfi Bengü. The melodramatic narrative constructed in these films would later significantly influence Turkish cinema as well.

Studio Misr founded in Giza, 1935

Source: Wikipedia

After the Second World War, countries in the Global South gained political independence, and there was a significant influx of migrants from these countries to the prosperous West. These countries, which were largely no more than fronts in the world wars and were primarily governed by colonial policies rather than being policymakers, were predominantly Muslim-populated regions. There were multiple social and economic reasons for migration. Western countries benefited from this influx of migrants by replacing the workforce lost during the war and providing employment for their developing industries.

The migration flow has also had a significant impact on cinema. However, before delving into the cinematic representation of mass migrations, let us examine it on an individual level. Firstly, it should be noted that the lack of cinema education and infrastructure in Muslim countries, or their non-existence altogether, forced many individuals to migrate to Western countries, albeit mainly out of necessity. For example, many Turkish citizens received education in cinema and photography in Europe. However, they were compelled to return to their countries with the outbreak of the Second World War. After their return, their involvement in the cinema greatly influenced Turkish cinema (Onaran, 1994, pp. 41-42). In countries under Ba’athist regimes, on the other hand, sending individuals abroad for cinema education was implemented as a state policy. Thus, Syria and Iraq transferred directors from Egypt and Lebanon to make films in their countries. In some cases, filmmakers were forced to migrate to other countries, mainly to Europe, for political reasons, and they continued with their productions there.

The lack of cinema education and infrastructure in Muslim countries, or their non-existence altogether, forced many individuals to migrate to Western countries, albeit mainly out of necessity.

Diasporic Cinema

The phenomenon of diasporic cinema resulting from mass migration flow is worth examining beyond the individual level as it sheds light on the experiences and transformations of Muslim communities in Western countries over decades, as articulated by Hamid Naficy (2024). Muslim diasporic communities exist in various parts of Europe, including Pakistanis in Britain, North Africans in France, and Turks in Germany. The individuals comprising these communities do not fully belong to their homeland nor entirely to the society they currently reside in. Therefore, they construct a unique identity as diasporic communities.

The phenomenon of diasporic cinema resulting from mass migration flow is worth examining beyond the individual level as it sheds light on the experiences and transformations of Muslim communities in Western countries over decades, as articulated by Hamid Naficy.

The transformation in the way this identity is presented over time can be easily read through the films. While issues such as integration problems, exclusion, racism, and identity fragmentation are prominently featured in the first two or three generations, and diasporic solidarity is emphasized (Higbee, 2013), today, such issues have largely been overcome. Although cultural, religious, and physiological differences are not entirely ignored, the differences between minority groups and the majority have largely given way to interconnectedness. For example, Fatih Akın, born in Germany, while touching upon the sensitive issues between Turkishness and Germanness in his films, does not convey negative messages about integration. He constructs a multicultural framework and focuses on raw human stories. Similarly, director Rachid Bouchareb, of Algerian descent, may make films about Algeria and Algerians, but fundamentally, he is a French filmmaker, creating popular productions for a French audience. These and similar filmmakers have become significant parts of their national cinemas and do not see themselves as pioneers in highlighting the struggles of a diasporic community.

Understanding the two main axes of contemporary cinema is essential to comprehend migration-themed films made by Muslim communities. On one side of the coin, there is national cinema, while on the other, there is art cinema. National cinema refers to a structure where films are produced within a national context, as implied by its name. These films are often only presented to a specific audience. In these productions, the story progresses in a more linear manner, with fewer formal experiments. The meaning constructed in this context is also more suitable for national understanding. National allegories constructed throughout the film culminate in catharsis at the end; in other words, order is restored and justice prevails. On the other hand, art films are productions primarily supported by private and national funding institutions, mostly in Europe, and are presented to audiences mainly at film festivals and websites showcasing art cinema. The productions prioritize global messages over national contexts. A linear flow of content and form is not strictly followed. Art films, along with films rooted in local contexts in many national cinemas, are presented to a global audience. However, only art films might be produced in many countries due to the lack of national production, distribution, and screening networks.

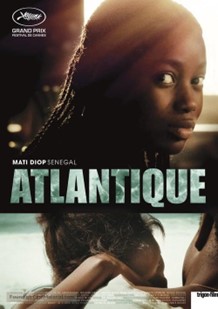

In many African countries, film production takes place within this context. Since many African filmmakers have been educated in Europe, have close ties with Europe and even live there, migration is one of the dominant themes in African cinema. Unlike national productions, achieving catharsis is not a priority in these films. Instead, they convey global messages, prioritizing the appreciation of festival audiences. Une Saison en France (A Season in France, 2017), directed by Chadian filmmaker Mahamat Saleh Haroun, provides a case in point. The film portrays a person who flees to France and emphasizes the universality of values such as fatherhood, love, and the struggle for survival. Similarly, Atlantique (2019), directed by Senegalese filmmaker Mati Diop, focuses on labor exploitation and family pressure in Senegal through the love story between a person attempting to migrate from Senegal to Spain and his lover left behind. Throughout the film, young people drowned in the Atlantic Ocean appear as zombies in the bodies of different individuals to take revenge.

Filmmakers from Muslim countries direct a notable portion of contemporary films that share the theme of migration, and the economic, social, political, and cultural issues that force Muslim populations to migrate are portrayed by directors in these films. However, the fact that these films are supported mainly by European funding organizations and integrated into the global art cinema network prevents a discussion environment among Muslims through these productions. As a result, the problems experienced and awaiting solutions cannot go beyond serving a background of the productions presented to the global audience and adorned with aesthetic concerns. Except for Turkey and Qatar, hardly any Muslim country prioritizes supporting global cinema, and cinema, in general, is not widely recognized as a platform for discussion. Therefore, this important art form is not utilized to its fullest potential. Moreover, the ongoing discussions predominantly unfold within a framework established by the West.

References

Higbee, W. (2013). Post-beur cinema: North African emigré and Maghrebi-French filmmaking in France since 2000. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Mejri, O. (2014). The birth of North African cinema. L. Bisschoff & D. Murphy (Ed.), In Africa’s Lost Classics: New Histories of African Cinema, 24-34. New York: Legenda.

Naficy, H. (2024). Aksanlı sinema: Sürgüne ait ve siyasporal film yapımı. Istanbul: Ayrıntı Publishing.

Onaran, A. Ş. (1994). Türk sineması (I. Cilt). Istanbul: Kitle Publishing.