Can the Subaltern Speak Online?

Editor's Note: This article is based on the findings of the TÜBİTAK-supported project titled "Suriyeli Göçmenlerin Entegrasyonu Bağlamında Dijital Okuryazarlık ve Dijital Vatandaşlık Seviyelerinin Araştırılması" (Project Director: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Haldun Narmanlıoğlu, Project Researcher: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Serkan Bayrakcı, Project No: 122G140).

In its broadest sense, the term "subaltern" refers to that which is lower or subordinate. However, the concept does not denote a specific, singular, and immutable group, community, or social unit. The Subaltern Studies Collective has defined the term to describe those positioned lower in terms of class, caste, age, and gender. In her work, Can the Subaltern Speak? Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak develops a critique that examines the subaltern not only in class terms but also through language, religion, ethnicity, and gender. The question "Can the subaltern speak?" is linked to the issue of representation for the subaltern. The most significant problem is making the voices of the subaltern heard. Spivak states that the term "voice" is metaphorical, referring to the lack of necessary infrastructure for speech acts. According to her, no one attempts to listen to these "silenced voices." Thus, the answer to the initial question should be "The subaltern cannot speak." However, social mobility has largely shifted to the Internet today. The Internet, being accessible to everyone, serves as an important alternative infrastructure for subaltern groups. In this regard, the question arises about how Syrian migrants, the largest subaltern group currently living in Turkey, use the Internet.

The research, which explores the internet practices of Syrian migrants in Türkiye by asking, "Can the subaltern speak online?" has led to quite interesting outcomes. The study involved in-depth face-to-face and online interviews with a total of 37 people (22 men, 15 women) and showed that migrants are unable to take full advantage of the vast opportunities offered by the Internet and, in turn, have become more introverted.

Fading Connections

Many studies conducted in Europe show that migrants can maintain their old connections in their homelands through the Internet while also forming new ties with the host societies. However, the situation is quite different for Syrians living in Turkey. Migrants in Türkiye are hesitant to stay in touch with their social circles back in Syria because of the political situation there. Particularly, those with relatives in areas controlled by the Syrian state are afraid of connecting with their old social circles through social media or instant messaging and communication apps like WhatsApp. Many migrants have expressed that due to the belief that internet communication is being "monitored" by the Syrian state, they avoid forming deep connections lest they harm those they've left behind.

The biggest obstacle to establishing new connections in Türkiye is their "Syrian" identity.

Prejudice as a Barrier to Forming New Connections

When considering the potential for forming new social ties in Türkiye, Syrian migrants have reported difficulties in communication due to prejudice. They noted that during the first years of their migration, they were welcomed with more tolerance, but now they are hesitant to establish relationships because they see that their perception by society is largely negative. The biggest obstacle to establishing new connections in Türkiye is their "Syrian" identity.

When we examine their involvement in public debates, we see that Syrian migrants are a "subjectless subject." Despite being the main "object" of public discussions concerning migrant issues in Türkiye, they are unable to produce discourse as "subjects." The primary reason for this barrier is the prejudice against migrants, especially Syrians, in public debates, regardless of the cause. Furthermore, Syrians cannot participate in public discussions in their homeland. They stay away from Syrian public debates due to the fear of harming the old ties they left behind and the constant fear of "deportation." They believe that if they participate in these discussions, their writings and posts will be recorded and could put them in a difficult position if they are deported. In both cases, the source of fear is "digital surveillance," which also hinders their deep connections with old social ties.

Migrants also fit another definition of the subaltern as people and groups that are disconnected from social mobility as they are unable to engage with and are excluded from social mobility in the digital realm.

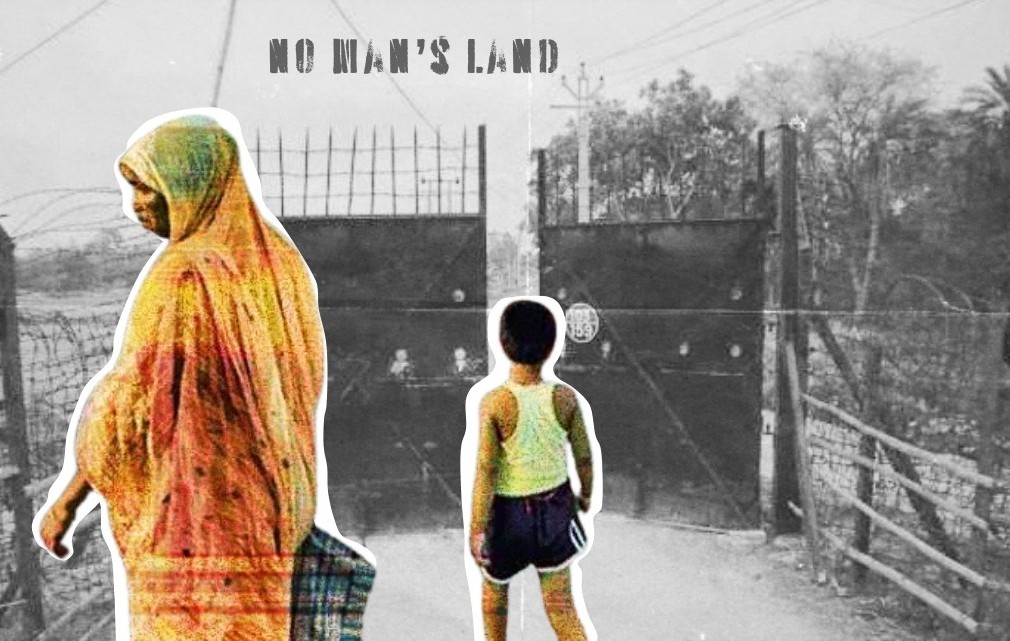

The potential for participating in public debates and expressing their identities through digital communication seems unlikely for Syrian migrants. Whether in Syria or Türkiye, when they attempt to discuss issues related to themselves, their future, identity, or problems, they encounter labels such as "foreigner," "traitor," or "the other." In this sense, they are caught between two places (Syria and Türkiye) in a state of liminality. This liminality and lack of belonging result in them being "unable to speak" or, if they do speak, being "unheard" or "silenced" in public debates. These characteristics, indeed, align migrants with the definition of the subaltern, who cannot represent or express themselves and lack a voice. Additionally, migrants also fit another definition of the subaltern as people and groups that are disconnected from social mobility as they are unable to engage with and are excluded from social mobility in the digital realm.

Online Economic Activities

Syrian migrants are quite active in the digital world in terms of economic activities. However, their economic activities are also largely inward-oriented. They extensively use Arabic websites, social media groups, and channels to find jobs and workers. In terms of commerce, there is minimal interaction with non-Syrians. Due to prejudice and language barriers, Syrian migrants primarily carry out their business transactions among themselves, unable to engage in buying and selling relationships with Turkish citizens. However, commerce between migrants and locals is possible if the migrants speak Turkish fluently or if there is already a sense of trust between the parties.

The Role of Internet in Education

Since the Industrial Revolution, mass education has continued in various forms, and with the advent of new communication technologies, it has become more flexible, adapting to rapidly developing digital information. Education and self-improvement, which are among the most significant practices of digital citizenship, facilitate individuals' participation in both their national communities and the global online community by accessing digitalized information. The monopoly of governments over education is weakening worldwide and gives rise to a flexible structure where people access information according to their needs.

Syrian migrants have not often had the opportunity for regular and formal education because they must work and complain about it. After arriving in Türkiye, only a few have taken Turkish language courses at private institutions, education centers of private universities, or those of Ankara University's Turkish and Foreign Languages Application and Research Center (TÖMER). Yet, since they had to work, they had to also leave these courses without completing them. Hence, Syrian migrants use the Internet to learn Turkish and improve themselves in various fields.

No one is trying to listen to the "silenced voices" in the digital space. However, being open to everyone, the Internet is an important alternative for public participation and speech.

Interpreting the research findings in relation to subaltern studies, we can argue that Syrian migrants remain inwardly focused and outwardly silent. Unfortunately, it is not possible to draw a different conclusion considering the digital practices of subaltern migrants in this context. Due to prejudices, fear, trust issues, and language barriers, the internet practices of the Syrian migrants are quite limited. No one is trying to listen to the "silenced voices" in the digital space. However, being open to everyone, the Internet is an important alternative for public participation and speech. Silence is partly related to the subaltern's inability to speak and partly to whether the speech reaches its audience. The sharp boundaries mean that the subaltern's voice is not heard. Speaking is connected to listening, and when there are those who do not want to listen, silence prevails even when the subaltern speaks.

In conclusion, as explained above, Syrian migrants in Türkiye are unable to form new connections through the Internet, particularly in terms of integration. They refrain from participating in public discussions that could contribute to democracy in both their homeland and Türkiye. In the economic domain, the inward nature of migrant networks hinders integration, perpetuating the isolation of Syrians. Participation in economic life through these inward networks should be problematized in the context of integration and investigated further in future studies. Additionally, while increasing economic opportunities for one group, how these networks affect other groups is another issue that requires further exploration.

References

Alencar A., Tsagkroni V. (2019). Prospects of refugee integration in the Netherlands: Social capital, information practices and digital media. Media and Communication, (2), 184-194.

Kalter F., Irena K. (2014). Migrant networks and labor market integration of immigrants from the former Soviet Union in Germany. Social Forces, 4(92), 1435–1456.

Kaufmann, K. (2018). Navigating a new life: Syrian refugees and their smartphones in Vienna. Information, Communication & Society, 21(6), 882–898.

Khoja, J. (2020). Digital media in refugees’ everyday life and integration. [Master’s Thesis, Lund University].

Leurs, K. (2017). Communication rights from the margins: Politicising young refugees’ smartphone pocket archives. International Communication Gazette, 79(6/7), 674–698.

Maggio J. (2007). Political theory, translation, representation, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Alternatives, 32(4), 419-443.

Spivak, G. C. (2020). Madun konuşabilir mi? E. Koyuncu (Trans.), Ankara: Dipnot Publishing.

Yetişkin, E. (2013). Postkolonyal düşünce ve madun çalışmalarından neler öğrenebiliriz?. 13. Ulusal Sosyal Bilimler Kongresi, Ankara, 4-6 December 2013, Turkish Social Sciences Association.

Haldun Narmanlıoğlu

İstanbul Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi Gazetecilik Bölümü’nden 1999 yılında mezun oldu. Çeşitli ulusal haber ajansı ve gazetelerde görev yaptıktan sonra akademik hayata başladı. 2014 yılından beri Marmara Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi’nde öğretim...

Haldun Narmanlıoğlu

Haldun Narmanlıoğlu