In the realm of civil societies and human rights advocacy, Malaysia exhibits a complicated landscape, where the balance between state power and people has been a subject of ongoing debate. Moreover, democratic backsliding in this country has been significant (Bünte & Weiss, 2023). As a predominantly Muslim state, Malaysia’s approach to human rights has been influenced by the interaction of religious, cultural, economic, and political factors, often leading to a combination of challenges and progress. Political pressures limit civil society organizations (CSOs) in their ability to address sensitive issues and criticize government policies. Monitoring and harassment of activists add to the challenges, creating an atmosphere of fear and self-censorship. These difficulties thwart CSOs’ effectiveness in promoting equality and impartiality, forcing them to run in restrictive surroundings that weaken their impact and independence. There are also organizations in this country that experience co-optation and the NGO-ization of resistance, raising questions about the uncivil side of civil society (Syed Annuar & Ismail, 2023).

Despite facing significant challenges, Malaysian civil society organizations have expressed workability and adaptability. These organizations have been active in advocating issues such as freedom of expression, minority rights, environmental protection, indigenous rights, and social justice (Lim, 2017). Their efforts are valuable in mobilizing grassroots support, expanding international networks, and strengthening their causes. Indeed, some organizations are recognized for their role in driving governmental change and enhancing political awareness and participation among the people. A notable achievement of CSOs in Malaysia is their positive advocacy for electoral reforms through the BERSIH [The Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections] movement. BERSIH has been instrumental in pushing for greater transparency in Malaysia’s election system, leading to significant reforms aimed at improving democratic practices (Khoo, 2024).

Southeast Asia Globe, 2016

Navigating Islamic Values and Civic Engagement

Malaysia’s tenth Prime Minister, Anwar Ibrahim, instituted the concept of “Malaysia MADANI”* to guide the country’s governance and public policy. This concept emphasizes political, economic, and cultural empowerment grounded in inclusiveness and civic consciousness. It prioritizes justice as a fundamental principle of the state philosophy and positions Islam as central (Azman & Abdul Rahman, 2023). This approach seeks to ensure fairness for all citizens and prevent discrimination, with the objective of creating an equitable and balanced society. MADANI’s idea is based on six main thrusts, namely (i) sustainability, (ii) prosperity, (iii) innovation, (iv) respect, (v) trust, and (vi) care and compassion. Furthermore, it emphasizes Maqasid Al-Shariah [objectives of sharia] as its core governing principle. Hence, Anwar’s primary conundrum is to translate the concept into tangible action (Musa, 2023), especially when this concept aligns closely with the objectives of civil society, democracy, and human rights.

Yet, a growing number of CSOs and activists that once anticipated reform under Anwar Ibrahim now criticize him because the current government has yet to address electoral reform and still employs undemocratic laws. For example, BERSIH recently criticized Anwar Ibrahim’s administration for its failure to fulfill electoral reforms, giving his government an “F” grade. The organization expressed disappointment and highlighted that no significant progress has been made on crucial reform demands essential for transparency, integrity, and democracy (Focus Malaysia, 2024). In addition, concerns include the Sedition Act, which forbids speech and actions that incite criticisms against the government or monarchy; the Communications and Multimedia Act, which controls communications and multimedia activities; the Universities and University Colleges Act, which oversees the direction of universities, including restrictions on student activities, the Peaceful Assembly Act that regulates public assemblies, and the Printing Presses and Publications Act which controls the presses and publications (MalaysiaNow, 2024). Thus, for CSOs, these laws are seen as problematic to democracy as they limit free speech, restrict media freedom, control academic independence, restrain peaceful assembly, and implement strict publication regulations, thereby suppressing dissent and critical discourse.

At the same time, the concept of liberalism, which highlights individual freedoms, human rights, and secularism, still regularly clashes with prevalent societal, religious, and governmental norms in Malaysia. CSOs that support liberal ideals may be in opposition to laws, policies, and norms that are conservative and limiting. For instance, attempts to promote gender equality or LGBTQ+ rights can be provocative in a context where traditional values and religious norms deeply influence public and political views. On the other hand, society in this country is also encountering cosmopolitan challenges due to globalization and increasing understanding of marginalized people (Muniandy, 2012).

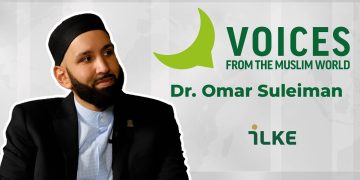

Therefore, CSOs in this country might be able to help in navigating Islamic values and civic engagement. Among the approaches that may be adopted are promoting dialogue and inclusive discussion, as well as linking the gap between traditional values and human rights. They can also encourage civic education that is associated with Islamic principles to improve active participation in community and political life (Malik et al., 2018). Principles that can be considered include compassion (rahmah), equality (musawah), justice (adl), community (ummah), and consultation and participation (shura). Additionally, by tackling social issues through an Islamic context, CSOs in Malaysia can strengthen human rights and social justice causes while respecting religious and cultural beliefs. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that although human rights are fundamentally aligned with Islamic principles, perspectives on human rights may differ between Western and Islamic interpretations (Mohamed Adil & Ahmad, 2014). These are the areas that CSOs in this country need to examine if they want to enhance their activism.

Shaping Global Human Rights Discourse

As Malaysia gradually integrates into the global community, CSOs also play a pivotal role in advocating for justice, equality, and human dignity while engaging with both universal human rights principles and the country’s religious and socio-cultural contexts. At international forums and human rights bodies, they actively participate in advocacy and lobbying, provide policy recommendations, join global human rights campaigns, and work together with partners and networks (Chaney, 2023). Many scholars also acknowledge that organizations like CSOs considerably influence foreign policy in their respective countries. In Malaysia, the sympathy and supportive stance of leaders, activists, and the public towards Palestinians have contributed to the increase of many Muslim faith-based CSOs. Nevertheless, CSOs advocating for the Palestinian cause have to adopt an inclusive approach, recognizing that the issue transcends religious dimensions and is fundamentally a universal humanitarian concern (Nazri, 2022).

Middle East Monitor, 2018

Middle East Monitor, 2018

Additionally, an intriguing aspect of the global human rights discourse is the debate about the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) among organizations in Malaysia. The UPR is a mechanism established by the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council to review the human rights records of member states. It extends an important platform for encouraging human rights and influencing policy reforms at both national and international levels. For the Muslim world, the UPR is principally crucial as it enables a dialogue that promotes an inclusive approach that respects Islamic values while addressing universal human rights issues. CSOs in this country have dynamically engaged in the UPR process since Malaysia’s initial review cycle, with their participation growing over time. But, despite their active involvement, this engagement has been somewhat constrained within a procedural democratic framework. Because controversial issues and matters related to substantive democracy have not yet been fully accepted or embraced within society and by the state. Consequently, addressing these issues remains difficult and is often avoided in discourse (Beh et al., 2020). Moreover, organizations that advocate for the UPR face challenges because it is frequently perceived as a liberal agenda that could potentially impact the position of Islam in Malaysia (Mohd Hedzir & Yahya, 2018).

In addition, Malaysia is a member of several international organizations, including the ASEAN Civil Society Conference/ASEAN Peoples’ Forum (ACSC/APF) and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). By participating in these networks, CSOs in Malaysia can obtain better access to international platforms, resources, and alliances that enhance their activism and build their competency. Moreover, these networks also provide opportunities for sharing best practices among CSOs. Consequently, this involvement not only improves their capability to address local issues but also strengthens their impact on both regional and international levels, leading to more effective and widespread outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the experience of civil society organizations (CSOs) in Malaysia highlights the crucial role that grassroots advocacy plays in framing human rights discourse at the national and international levels. Despite facing sizable obstacles, Malaysian CSOs have leveraged international collaborations, prevailing advocacy approaches, and mobilization to achieve significant change. The enduring efforts of these groups have shown the ability of community-driven initiatives by CSOs to contest state policies and improve human rights agendas. Their work emphasizes the importance of resilience and adaptability of CSOs in human rights advocacy, suggesting valuable lessons for similar movements globally. Therefore, by continuing to foster collaboration and engage with various stakeholders, CSOs in Malaysia not only contribute to nationwide progress but also set a lesson for international human rights advocacy.

*Editor’s Note: It translates to “Civilized Malaysia” in English.

References

Azman, M.A., & Rahman, N.A. (2023). Application of the concept of Malaysia MADANI in public policy: Cultivating harmony in diversity. International Journal of Advanced Research in Education and Society, 5(4), 29-43.

Beh, S., Abdullah, N., & Tumin, M. (2020). Universal periodic review: The role of civil society organisations in Malaysia. Journal of Administrative Science, 17(2), 156-185.

Bünte, M., & Weiss, M. L. (2023). Civil society and democratic decline in Southeast Asia. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 42(3), 297-307.

Chaney, P. (2023). Civil society perspectives on rights and freedoms in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. European Journal of East Asian Studies, 193-228.

Focus Malaysia. (2024). Putrajaya gets an ‘F’ from Bersih for failing to enact electoral reforms. Retrieved from https://focusmalaysia.my/putrajaya-gets-an-f-from-bersih-for-failing-to-enact-electoral-reforms/#google_vignette

Khoo, Y.H. (2024). The Bersih movement and political rights in Malaysia. Facal, G., Lafaye de Micheaux, E., & Norén-Nilsson, A. (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of political norms in Southeast Asia. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lim, J. B. (2017). Engendering civil resistance: Social media and mob tactics in Malaysia. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 20(2), 209-227.

MalaysiaNow. (2024). Groups dismayed by Anwar’s failure to protect human rights.Retrieved from https://www.malaysianow.com/news/2024/07/05/groups-dismayed-by-anwars-failure-to-protect-human-rights

Malik, M., Safarudin, S., & Mat, H. (2018). Islamic NGO as another actor of civil society: The case of Pertubuhan IKRAM Malaysia (IKRAM). Ulum Islamiyyah, 23, 27-46.

Mohamed Adil, M.A., & Ahmad, N.M. (2014). Islamic law and human rights in Malaysia. Islam and Civilisational Renewal Journal, 5(1), 43-67.

Mohd Hedzir, M.H., & Yahya, M.A. (2018). Understanding the concept of compassion in the issue of the pluralistic society in Malaysia: An analysis of the missionary movement stand of IKRAM and ISMA. Jurnal Hadhari, 10(2), 243-257.

Muniandy, P. (2012). Malaysia’s coming out! Critical cosmopolitans, religious politics and democracy. Asian Journal of Social Science, 40(5/6), 582-607.

Musa, M.F. (2023). The evolution of Madani: How is 2.0 different from 1.0? Singapore: ISEAS Publishing.

Nazri, A.S. (2022). Malaysian NGOs in humanitarian issues of Palestine: Aman Palestine Berhad. Sains Insani, 7(1), 7-16.

Syed Annuar, S. N., & Ismail, M. T. (2023). The challenges of civil society organisations: NGO-isation of resistance in Malaysia?. Intellectual Discourse, 31(1), 257-282.