Farha: Testimony of the Nakba through Cinema

Based on a true story, the Jordanian film Farha tells the story of what happened in Palestine through the eyes of a young girl named Farha in 1948, the year of the "Nakba" (Catastrophe), which marked the establishment of the State of Israel. On 14 May 1948, on the day when Israel declared itself a state and Zionist militants began looting villages in many parts of Palestine and forcibly evicting people from their homes, Farha, who was locked in a basement by her father for safety, watches the atrocities in her village from the tiny window of the basement. Thus, as a cinematographic stance, director Darin Sallam presents the story only from Farha's point of view, making the viewers witness all the events along with Farha.

Another point worth highlighting in connection with the theme of "bearing witness" is that although the film premiered at the Toronto Film Festival in 2021, it gained prominence when it was released on Netflix in 2022. The release of this film, which presents the events in Palestine in their purest form in contrast to the longstanding Israeli and Western media propaganda, on a platform like Netflix with millions of subscribers worldwide was deemed unacceptable, especially by Israeli politicians. In fact, former Minister of Finance Avigdor Liberman accused the film of engaging in anti-Israel propaganda and "creating a false pretence and inciting against Israeli soldiers" (The Times of Israel, 2022). this regard, the film not only emphasises personal memories and the reality of individual and collective memory but also holds the power to critique and even challenge the media, especially the mass media, hegemony that has persisted for years.

Farha becomes more than a film with historical and emotional depth; it becomes a documentary, and even more, a vibrant testimony of the lived and ongoing Palestinian experience.

The film unfolds by painting a vivid picture of Farha's traditional and simple life. Eager to pursue education in the city, she finds herself in a persistent struggle with her father, the village governor. However, the narrative skillfully avoids falling into the stereotypical traps of the "Middle Eastern, oppressive, Muslim father" or the predictable arcs of the "young woman fighting for her right to education" and the ensuing struggle for "freedom." Instead, it subtly introduces the looming presence of an approaching occupation. Farha loses her family, her home and her entire future, including her education in the city, on the day of the "catastrophe" created by the Israeli occupation forces, while her father allows and supports her education. On the day of the "catastrophe" realised by the Israeli occupation forces, Farha, despite her father's support for her education, tragically loses her family, home, and the promising future that included education in the city. While the film maintains a fluid pace until the occupation forces enter the villages, and Farha is portrayed with a sense of "joy" reminiscent of her name, the storyline gradually slows down as the ominous threat of occupation becomes tangible. Locked in the basement, Farha's confinement marks a turning point where the rhythm of the film slows down, inviting the viewer to immerse themselves more deeply into her character. In this sense, the symbolic significance of the basement gains prominence. The dark and claustrophobic atmosphere surrounding Farha as she enters the basement space becomes a poignant reflection of the Gaza Strip, often referred to as an "open-air prison" due to blockades. The basement, reflecting a microcosm of Gaza, transforms into a suffocating space, where those who have witnessed or been forced to witness the atrocities in Palestine since 1948, are metaphorically suffocated alongside Farha. The stifling air not only slows down the unfolding moment but also integrates the viewer into Farha's most basic and humane actions, such as her frantic search for water or a suitable place for personal needs. The film artfully captures her anxiety about her father's whereabouts and the sorrow she experiences witnessing the harsh realities around her. In an interview with Time magazine, Sallam emphasised her intention not to reduce Farha to a mere "number" (Syed, 2022). Rather, she sought to depict her as a "normal" individual with dreams, much like anyone else. From this perspective, the film transcends being a mere portrayal of 1948 or the historical experience of a specific Palestinian child or young girl. It serves as a reflection on the dehumanisation of Palestinians reduced to statistics in the news, highlighting the systematic ethnic cleansing and genocide perpetrated by Israel against Palestinians. Thus, Farha becomes more than a film with historical and emotional depth; it becomes a documentary, and even more, a vibrant testimony of the lived and ongoing Palestinian experience.

Locked within the confines of the basement, Farha experiences a temporary detachment from the outside world. Her first encounter with external reality unfolds when gas bombs cast into the village enter the basement. The initial resonance of bomb blasts fills her ears, and soon, the entire basement is engulfed in gas, transforming the already claustrophobic space into a literal suffocating environment. The first thing Farha sees when she looks out of the small window of the basement after a long time is another Palestinian family who took refuge in Farha's house while fleeing from the occupation forces; and especially the Palestinian mother who had to give birth right in the garden of the house. As Farha tries to look at the garden of the house from under the door of a basement, through the small window and again through the gaps of the door, the viewer is left contemplating what will happen to this family after the birth of the baby and whether they will be able to hide from the soldiers; as the curiosity and tension increase, it harmonises with Farha's movements. However, this heightened activity is abruptly interrupted when Israeli militants position themselves in front of the house, apprehending the father who sought refuge there. Farha falls into a hushed silence, a witness to the atrocity unfolding before her eyes. The militants drag the other family members, including two children, from their hiding places in the house, leading them to the garden, where all are murdered except for the newborn baby. Yet, this massacre scene is not shown directly to the viewer, as the director wants to reflect "[Farha’s] feelings on what she’s witnessing" (Syed, 2022), not the war. While Farha witnesses the unfolding atrocities right in front of her eyes; the viewer, the other witness of the Nakba, only hears the echoing sound of gunfire. After a brief moment of the sounds of this atrocity, a deathly silence ensues, only to be broken by the cries of a newborn baby, abandoned to fate in the garden of the house… Then Farha's voice is heard accompanying the sounds of the baby, and then the baby, like "all the children in the neighbourhood who slept long ago" as mentioned in the lullaby Farha sings, also succumbs to silence.

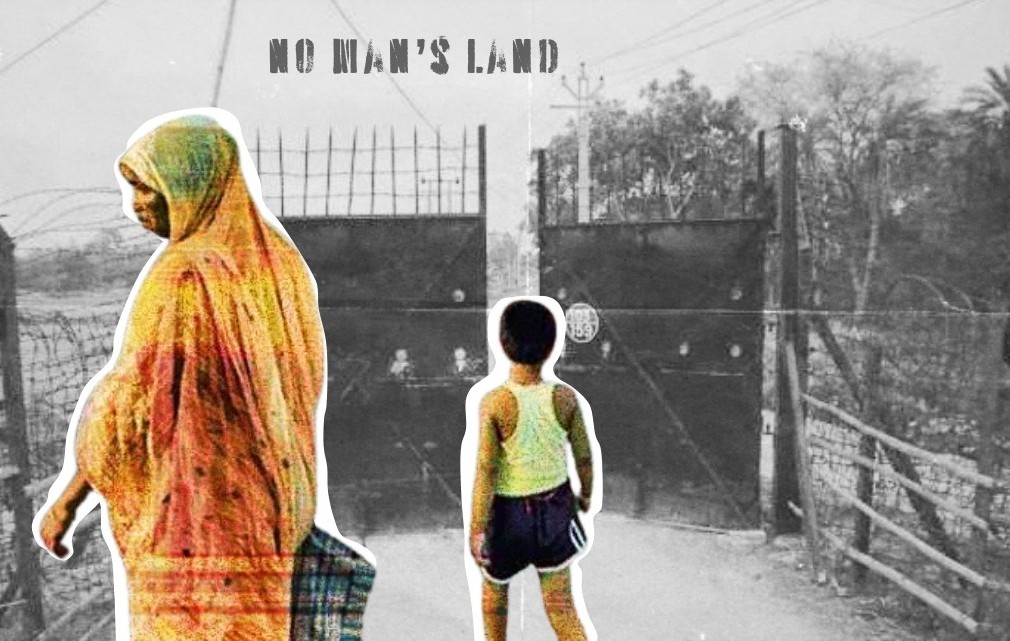

At the end of the film, Farha, overwhelmed by the weight of all these events she witnessed, breaks the lock of the door with the gun she finds among the sacks in the basement and comes out after days of confinement. The first thing she does is to drink water from the fountain in the garden, as she could not find water and had to drink pickle juice during her confinement. This image reminds the audience of the reality of the water crisis in Gaza (Visualizing Palestine, 2021), where 97% of the water is contaminated and undrinkable due to the ongoing occupation and blockade. The scene continues with another symbolic image: Farha looks up at the sky after a long time and sees birds flying in the sky. Although the sky and birds are associated with freedom and hope in traditional storytelling, when Farha looks down, she sees the dead body of the baby left behind, and the magic of this traditional narrative is shattered. The film concludes with Farha, exhausted by the trauma of all that has happened, walking on a long road that leads to the sun in a barren wasteland.

Farha is not only the story of Sallam's mother's friend, but in fact, it is the story of all Palestinians who experienced the Nakba in 1948 and continue to experience the same catastrophe today.

In the end credits, we discover that this is the narrative of a young girl named Radiyyeh, who, having fled to Syria, shared her story with someone else with the intention of preserving it for future generations. Director Darin Sallam also says in an interview that the "someone else" to whom this story was told was her own mother (Syed, 2022). However, Farha is not only the story of Sallam's mother's friend, but in fact, it is the story of all Palestinians who experienced the Nakba in 1948 and continue to experience the same catastrophe today. In contrast to the wide spectrum of emotions portrayed throughout the film, especially the overwhelming despair, Farha's emergence from the basement and her path towards the sun, even though it seems endless, evokes hope and freedom for viewers, supporters of Palestine, and most importantly for all Palestinians who have lived through these traumatic events or heard about them from past generations.

References

Gaza Water (2021, September). Visualizing Palestine. https://www.visualizingpalestine.org/visuals/gaza-water-confined-and-contaminated

Syed, A. (2022, December 7). Why the Director of Netflix's Farha Depicted the Murder of a Palestinian Family. Time Magazine. https://time.com/6238964/darin-sallam-farha-netflix-interview/

The Times of Israel (2022, November 30). Ministers condemn 'terrible' Jordanian film about 1948 war slated to hit Netflix. The Times of Israel. https://www.timesofisrael.com/ministers-condemn-terrible-jordanian-film-about-1948-war-slated-to-hit-netflix/

Elif Sağır

Elif Sağır graduated from Boğaziçi University, Department of Western Languages and Literatures in 2023. She is currently pursuing her master's degree in the Department of Sociology at Boğaziçi University. She is the editor of The Platform: Current Mu...

Elif Sağır

Elif Sağır