Fear, Politics and Students in Kashmir

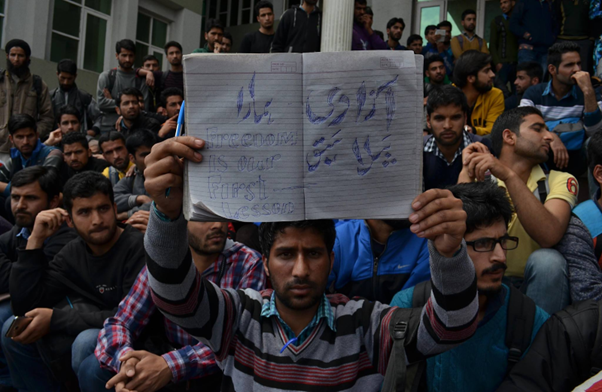

Photograph: Protest organized by Kashmir University Students Union, May 2010

In 2009, fearing that the annual convocation of the University of Kashmir, to be presided over by the then President of India, Pratibha Patel, might be disrupted, the university administration banned the Kashmir University Students Union (KUSU). A year later, its office was demolished. Formed in 2007 “as a pressure group to take up student issues” (Raina, 2007), the Union quickly engaged in anti-establishment politics, organizing protests against human rights violations and other such issues (Naqash, 2017). Two things are stark in these administrative decisions and the political positions of the Union: one, student politics is highly discouraged by university administration at the behest of the state authorities, and second, student politics is intimately connected to the politics of the right to self-determination in the region. Nevertheless, despite the ban, in 2017, the organization called for protests, and thousands of students, some even in their uniforms, turned to the streets chanting the slogans of freedom (Masood & Ehsan, 2018).

This brief history and influence of KUSU provide an insight into what student politics in Kashmir is about. In this article, I mainly focus on student politics in the post-accession period in the context of the ongoing struggle for self-determination movement in Kashmir. In 1947, as the British left the subcontinent, the former ruler of Kashmir was given the option to either join India or Pakistan or remain independent. Amid communal riots, massacres, and, subsequently, a war, the ruler decided to join India. Since then, a movement for the right to self-determination has been ongoing, which turned into a popular insurgency in the late 1980s. Huzaifa Pandith argues that unlike what is expected of student politics -of advocating student issues- student politics in Kashmir is markedly different. Rather, he notes, “it places itself squarely in the people’s struggle for self-determination and counter-colonial sentiment in the Kashmir Valley” (Pandit, 2019, p. 95). Thus, student-led agitations in Kashmir often have been initiated to counter government repression. From the late 1970s, student politics became more palpable. With the rise of organizations like Islami Jamiat Tulba (the student wing of the Jamaat-e-Islami) and Islamic Students League, the role of religion in politics took center stage. However, it also intensified the debate around the nature of the self-determination movement. For decades, the movement relied on dialogue with a very low-intensity insurgency accompanying it. However, for multiple reasons, not least student politics, it changed and effectively shaped the current insurgent movement, especially its high-intensity phase in the middle of the 1990s.

I am not interested in providing a more detailed historical timeline of the student movement in Kashmir or on university campuses; rather, I am interested in understanding what it means to be a student activist in a contested territory like Kashmir with a high degree of violence. However, I should note here that the spread of education affected Kashmiri society generally, and it is one of the main reasons that student politics is so attached to the politics of self-determination. Thus, for example, when a relic of Prophet Muhammad was stolen from a mosque, leading to massive protests, the students demonstrated in front of UN offices and demanded a plebiscite (Naqash, 2017). Mohd Tahir Ganie argues that contemporary youth in Kashmir are remarkably different from earlier generations due to their embeddedness in the social media ecosystem. However, the unique experiences of living in an armed conflict in the “post-9/11 world order, and the concomitant rise of Islamophobia/War on Terror discourses” influence the political consciousness of Kashmiri Youth. Yet, they have an organic link with earlier generations through the politics of Azadi (Freedom). This political consciousness, however, leads the Indian state to think about Kashmiri Youth from a security perspective (Ganie, 2022, pp. 97–98). The aforementioned case of KUSU is an apt example of understanding this. However, there is a grim reality also where hundreds of young Kashmiris (students) have been killed, maimed, tortured, or simply are languishing in jails.

In this situation, where politics is heavily securitized, and the threat to life is imminent, what does it even mean to be a student? What happens to her aspirations? In the last half a decade since India unilaterally revoked the autonomous status of the region, it might be easy to define such aspirations straightforwardly since the choice is obvious between life and fear. Does that mean the possibility of a student-led social movement is faint? It brings me to the points raised by Ganie that Kashmiri youth are embedded in a social media ecosystem with a lived experience in which the Muslim Question features prominently not just locally but globally. I am particularly thinking about Palestine and how social media has helped to understand the situation, especially when the mainstream has taken a very pro-Israel stand. The Palestinian context provides an ideal space where the politics of protest can be articulated, especially since Kashmir and Palestine have evoked solidarity towards each other (Javaid, 2023). However, such has not been the case, and one plausible answer to this predicament is fear and total control over life in Kashmir by the state. A report in the Associated Press noted that Indian authorities have “asked Muslim preachers not to mention the conflict in their sermons,” further adding that “the restrictions are part of India’s efforts to curb any form of protest that could turn into demands for ending New Delhi’s rule in the disputed region” (Hussain & Saaliq, 2023).

The Palestinian context provides an ideal space where the politics of protest can be articulated, especially since Kashmir and Palestine have evoked solidarity towards each other

Recently, Hafsa Kanjwal has made an argument that the early decades of India’s rule were marked by what Neve Gordon calls a “politics of life” in which the Indian government propagated development, empowerment, and progress to normalize its control over the region (Kanjwal, 2023). This theoretical category also explains the post-2019 situation but with a slight difference, as fear has been a profound part of everyday life. Student politics in universities is most affected by such situations since it comes into the way of aspirations. It might seem a grim picture, but it only reflects the slowness of adapting to new political realities. It is difficult to gauge the direction in which the student movement would move and what possibilities it would generate for a comprehensive social movement attached to the self-determination movement. What is required is perseverance and intense conversations about it.

References

Ganie, M. T. (2022). Claiming the streets: Political resistance among the youth. In M. Bhan, H. Duschinski, & D. Misri (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Critical Kashmir Studies, 97–114.

Hussain, A., & Saaliq. (2023, November 8). India bars protests that support the Palestinians. Analysts say a pro-Israel shift helps at home. AP News. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/article/india-kashmir-protests-israel-gaza-f4b431716decb1550522db2e49630d9e

Javaid, A. (2023, November 29). Why does the Palestinian cause resonate with Kashmiri Muslims? Sputnik News. Retrieved from https://sputniknews.in/20231129/why-does-the-palestinian-cause-resonate-with-kashmiri-muslims-5613579.html

Kanjwal, H. (2023). Colonizing Kashmir: State-building under Indian occupation. Stanford University Press.

Masood, B., & Ehsan, M. (2018, June 26). The Valley on Campus. The Indian Express. Retrieved from https://indianexpress.com/article/india/kashmir-valley-protest-on-campus-afzal-guru-naseem-bagh-shopian-4624268/

Naqash, R. (2017, June 5). Lessons in dissent: How students on campuses have shaped politics in Kashmir over the decades. Scroll.In. Retrieved from https://scroll.in/article/838842/lessons-in-dissent-how-students-in-campuses-have-shaped-politics-in-kashmir-over-the-decades

Pandit, H. (2019). Schools of resistance – a brief history of student activism in Kashmir. Postcolonial Studies, 22(1), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2019.1568171

Raina, M. (2007, June 24). Reborn: Kashmir campus politics. The Telegraph. Retrieved from https://www.telegraphindia.com/india/reborn-kashmir-campus-politics-after-a-decade-and-a-half-university-approves-revival-of-student-activism/cid/701330

Iymon Majid

Siyaset Bilimci olan Iymon Majid, Almanya'daki The Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities’de araştırma görevlisi olarak çalışmaktadır....

Iymon Majid

Iymon Majid