Heading Toward COP28: Effects of Climate Change on Muslim World

The 2022 publication of the report by the International Governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) paints a grim picture of the world’s future, marked by climate threats like ecosystem collapse, species extinction, intense heatwaves, and devastating floods. One of the primary factors driving this alarming scenario is the dramatic rise in global temperatures. The report released by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) indicates that temperatures during the period from 2013 to 2022 were 1.14 degrees higher than those before the Industrial Revolution (2022). Likewise, a study conducted between 2000 and 2019 revealed that global warming has led to a nearly two-fold acceleration in the melting rate of glaciers worldwide over the past two decades (Hugonnet, 2021, p. 728). Conversely, the elevation of sea levels and the escalation in oceanic temperatures are increasingly viewed as indications of a global climate crisis in recent times. Although there was a substantial reduction in carbon emissions during the COVID-19 pandemic due to mitigation efforts, the post-pandemic era seems to have witnessed greenhouse gas emissions reaching their peak levels (Bhanumati, 2022). What implications do the international efforts against these climate threats hold for developing countries with a significant Muslim population?

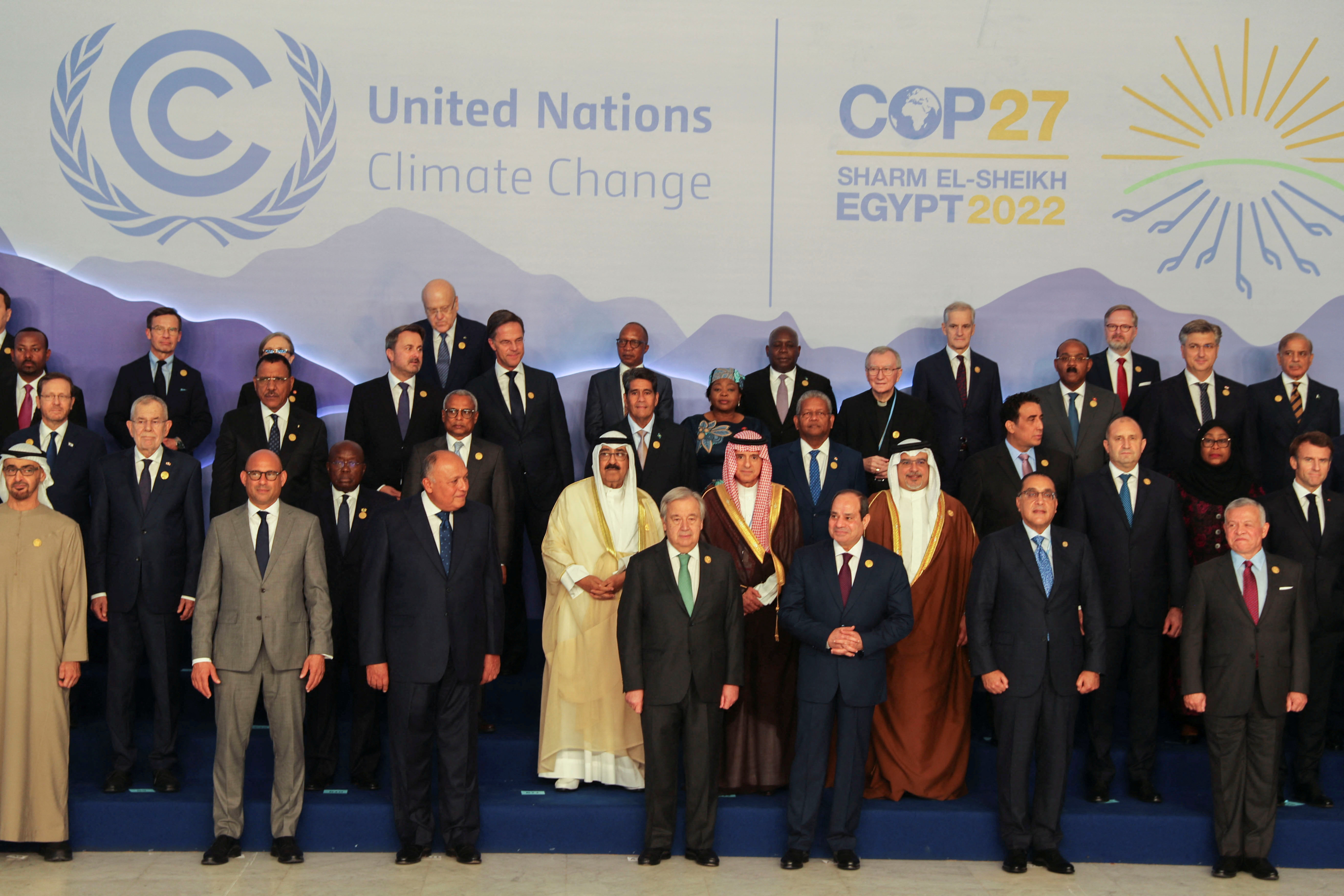

The COP27 Climate Change Conference was held in Egypt.

Global Efforts in Addressing Climate Change

Prior to addressing the question above, it’s essential to discuss climate change and the global efforts undertaken in this domain. Beginning with the Industrial Revolution, a phase has been entered where human activities, alongside natural shifts, have significantly impacted the climate.

Since that time, the rapid accumulation of greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere has been a consequence of various activities. The “United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)” was signed in 1992 and came into effect in 1994. Within this agreement, climate change is defined as “a change of climate that is directly or indirectly attributed to human activities, which alter the composition of the global atmosphere and are in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods.” In this context, greenhouse gas emissions are recognized as the foremost factor contributing to climate change (1994). Consequently, each country has committed to reducing their greenhouse gas emissions and maintaining these emissions at a certain level. While the agreement represents an initial step towards combating climate threats, its lack of substantial enforcement power or its limited enforceability has prevented it from holding binding authority among nations.

In 1997, within the scope of the agreement, the Kyoto Protocol was signed during the COP-3 Summit, rejuvenating global debates about the future of the climate. This protocol presented three distinct mechanisms aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions after the year 2000. These mechanisms are known as the Joint Implementation Mechanism, Clean Development Mechanism, and Emissions Trading. Joint Implementation involves a developed country with specified emission goals collaborating on projects for emission reduction in another developed country that also has emission reduction goals. In the country where the project is implemented, they earn credits called ‘Emission Reduction Units’ and can sell these credits to the country initiating the project. As a result, the investing country can utilize the obtained credits to potentially increase their greenhouse gas emissions. In essence, within the Protocol, this practice not only enables developed countries to meet their commitments but also contributes to boosting foreign capital investment in the countries where the projects are implemented.

Clean Development, distinct from the Joint Implementation Mechanism, entails a developed country with emission reduction targets earning Certified Emission Reduction credits through projects aimed at emission reduction in a developing country without such targets. In this process, the developed country gains the right to emit greenhouse gases equivalent to the amount of credits earned. Lastly, the Emissions Trading mechanism represents a market where countries with emission reduction targets can buy and sell emission credits (or, in other words, emission reduction rights) among themselves (Çelikkol, 2011, pp. 205-207). On one hand, these mechanisms offer climate-friendly investments to developing or less developed countries, aiming to facilitate their access to clean technologies through mechanisms like the Special Climate Change Fund or project-based approaches. On the other hand, they also aim to enable developed countries with emission reduction targets, such as the United States, Japan, and Canada, to achieve their greenhouse gas reduction goals under the Kyoto Protocol at a lower cost.

Another significant development was the signing of the Paris Agreement during COP-21 in 2015, which can be considered a pivotal milestone in addressing these climate threats. According to the agreement, all countries committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and limiting the global temperature increase resulting from such emissions to below 2 degrees Celsius compared to the pre-Industrial era, signifying a crucial turning point in addressing these climate threats. The paramount characteristic of the agreement that took effect in 2016 lies in its framework, delineating actions to provide climate finance from developed countries to those developing nations susceptible to the adverse impacts of climate change. However, the action plan known as the Nationally Determined Contributions has not yet materialized concretely (UNFCCC, 2015).

The Paris Agreement encompassed a provision for the periodic reassessment of National Determined Contributions every five years. As a result, the COP26 conducted in 2021 not only served as the inaugural comprehensive review of these contributions but also featured a written decision regarding the gradual phasing out of coal usage (UNFCCC, 2016). Nevertheless, considering the unmet greenhouse gas emission commitments by countries and the absence of provided financial assistance to impoverished nations, it becomes apparent that the undertaken steps have not effectively contributed in a practical manner.

COP27 Climate Conference and Third World Countries

“At the COP27 conference held in Egypt last year, Mia Mottley, the female Prime Minister of Barbados, who is a leader of a small island nation, stated, ‘We were the ones who financed the Industrial Revolution with our blood, sweat, and tears. Now, are we the ones who will also bear the cost of the consequences of the greenhouse gases resulting from the Industrial Revolution?’ Her words shed light on how developing or impoverished countries are compelled to shoulder a burden in combating the climate crisis.” (Greenfield, 2022). Therefore, the decision to establish a ‘Loss and Damage’ support fund for vulnerable countries highlights the significance of COP-27. Indeed, the Pakistani Climate Minister, Sherry Rehman, viewed this decision as the “first step toward climate justice” (Ebrahim, 2022). However, the failure of the resolutions made during COP-27 to materialize into concrete actions and the persistent uncertainties bring forth the question: Can COP-28 truly deliver climate justice for developing nations?

It is evident that developing countries affected by climate change lack the capacity to cover the total damages incurred. However, as we approach COP28 in the coming months, the specifics of what the “loss and damage” will encompass, who will provide and to what extent the fund will be established, as well as matters related to fund distribution, are still far from being clear. As an example, China, one of the world’s major economies, possesses a significant role in greenhouse gas emissions despite being categorized as a developing country. Nonetheless, it has not committed to any form of financial contribution. In contrast, developed nations suggest securing funding through sources like development banks and non-governmental organizations, while also advocating a focus on the most pressing cases to reduce the number of recipient countries. On the other side, despite the emphasis on gradually reducing fossil fuels and the targeted transformation plan during COP-27, there has been limited progress. The fact that the United Arab Emirates (UAE), set to host COP-28, ranks among the largest fossil fuel producers, dampens expectations concerning this advancement. Certainly, the statement of UAE’s leader, Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan, indicating their intention to continue producing oil and natural gas as long as the world needs it, seems to reinforce this viewpoint (Parker, 2023).

The Adverse Effects of the Climate Crisis on Muslim Societies

The impacts of climate change disproportionately pose greater challenges for impoverished populations. Particularly, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, where Muslims make up the majority, faces issues such as rapid population growth, prolonged internal conflicts, limited access to clean water, insufficient nutrition, restricted healthcare and education, and due to climate change, they are compelled to combat these problems even more intensely (Takian, 2022, p. 2777).

In other geographical regions, the average per capita water availability is approximately 7,000 m3 /year, whereas in the MENA region, water availability is merely 1,200 m3 /year (Zafar, 2021). Alongside the insufficiency of water availability in the region, desertification, changes in rainfall patterns, and rising sea levels severely impede the economic and social development of the regional countries. Consequently, the countries in the region lack sufficient capacity to advance their climate commitments and transition to a low-carbon economy. Hence, it can be said that the MENA countries are highly vulnerable to climate change (Namdar, 2021). Therefore, international actors with substantial roles in greenhouse gas emissions should collaborate and establish partnerships in addressing the climate crisis, taking into account the diverse capacities, resources, and infrastructures of the MENA nations.

In conclusion, we collectively recognize the potential threats posed by climate change. It is indeed disheartening to observe that the international endeavors aimed at addressing these threats have, over the years, fallen short of delivering lasting and sustainable progress. Moreover, a notable void exists within the international system concerning the fight against the climate crisis, leaving the entire transformation agenda at the discretion of major powers. To effectively confront the challenges presented by climate change, policymakers must take proactive measures to bolster the resilience of vulnerable nations against its effects. COP-28 should seize the opportunity to galvanize international cooperation through substantial economic transformation, thereby mitigating the repercussions of climate change.

References

Bhanumati, P., Haan, M. ve Tebrake, J.W. (2022). Greenhouse Emissions Rise to Record, Erasing Drop During Pandemic. IMF Blog. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3OPLx9E

Çelikkol, H., & Özkan, N. (2011). Karbon Piyasaları ve Türkiye Perspektifi. Dumlupınar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 31, 203-222.

Ebrahim, Z. T. (2022, November 4). Flood-hit Pakistan seeks loss and damage ‘compensation’ at COP27. Reuters. https://bit. ly/3KB4Q3O

Greenfield, P., Harvey, F., Lakhani, N., & Carrington, D. (2022, November 7). Barbados PM Mia Mottley launches blistering attack on rich nations at COP27 climate talks. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/45p9o5y

Hugonnet, R., McNabb, R., & Berthier, E. (2021). Accelerated Global Glacier mass loss in the early twenty-first century. Nature, 592, 726–731. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586- 021-03436-z

IPCC (2022). Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), Summary for Policy Makers. Retrieved on July 30, 2023, from https://bit. ly/447soEi

Namdar, R., Karami, E., & Keshavarz, M. (2021). Climate Change and Vulnerability: The Case of MENA Countries. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 10(11), 794. https:// doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10110794

Parker, C., & Dennis, B. (2023, January 12). UAE appoints oil exec to lead COP28 climate talks, sparking outrage. The Washington Post. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3rXBSoj

Takian, A., Mousavi, A., McKee, M., Yazdi-Feyzabadi, V., Labonté, R., & Tangcharoensathien, V. (2022). COP27: The Prospects and Challenges for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 11(12), 2776–2779. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2022.7800

UNFCCC. (n.d.). What is the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change? Retrieved from https:// bit.ly/3QzO4pK

UNFCC. (2015). Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-first session. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3OuL1MS

UNFCC. (2016). Decision-/CP.26. Retrieved from https://bit. ly/3OtDmOJ

WMO. (2022). Provisional State of the Global Climate. Retrieved from https://public.wmo.int/en/our-mandate/climate/ wmo-statement-state-of-global-climate

Zafar, S. (2021). Water Scarcity in MENA. EcoMena. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3qzUR82

Ayşe Kurban

Kadir Has Üniversitesi Siyaset Bilimi ve Uluslararası İlişkiler bölümünde yüksek lisans öğrencisi olarak eğitim hayatına devam etmektedir....

Ayşe Kurban

Ayşe Kurban