Protests Everywhere: What’s Really Going on with Indonesia's Economy

Protests in Indonesia have escalated from localized issues to widespread unrest, driven by rising living costs, stagnant wages, and inequality. Diverse groups, including students and workers, mobilize against state repression. The situation highlights structural economic weaknesses, raising concerns about stability and signaling deeper societal grievances around fairness and representation. *This analysis is written by Fatin Fadhilah Hasib, Meri Indri Hapsari, Dina Fitrisia Septiarini

Introduction: From Sporadic Protests to Daily Unrest

During most of Indonesia's post-reform era, protests were episodic, localized, and related to specific issues, such as corruption or regional elections. Now, demonstrations have become widespread, frequent, and multisectoral. From Jakarta to Surabaya and Pati, riots escalated sharply in August 2025 after violent clashes that killed several people and led to the arrest of thousands.

This paper argues that these protests are not random disturbances, but rather symptoms of more profound structural weaknesses in the Indonesian economy. Rising living costs, stagnant wages, and striking inequality have created fertile ground for unrest, while state repression has further radicalized demonstrations.

Economic Roots of the Unrest

Inflation in Daily Life

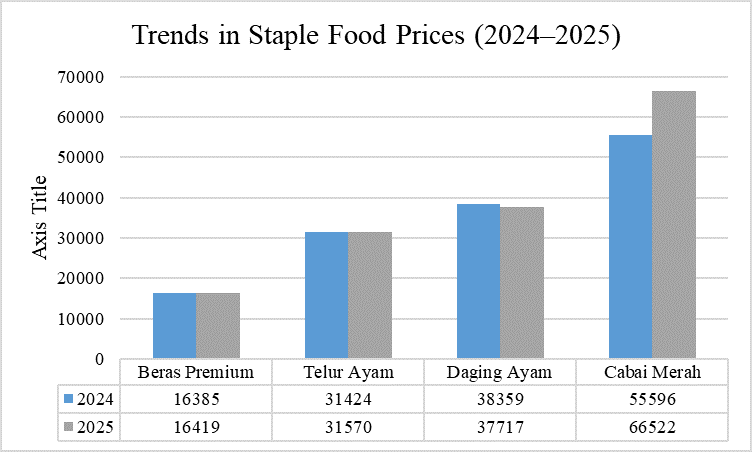

Although the official inflation rate appears to be “under control,” the year-on-year comparison of staple food prices tells another story. From August 2024 to August 2025, the price of premium rice increased slightly from IDR 16,385 to IDR 16,419 per kilogram, while eggs also rose marginally from IDR 31,424 to IDR 31,570 per kilogram. Chicken meat prices, on the other hand, edged down from IDR 38,359 to IDR 37,717 per kilogram. The most significant surge occurred in red chili peppers, which jumped from IDR 55,596 to IDR 66,522 per kilogram—an increase of nearly 20%. Even moderate shifts in rice and eggs, combined with spikes in volatile commodities like chili, strain household budgets and worsen the purchasing power of families already grappling with stagnant wages.

Visual 1: Trends in Staple Food Prices (2024–2025)

Source: Statistics Indonesia (BPS), 2025

Stagnant Incomes and Precarious Work

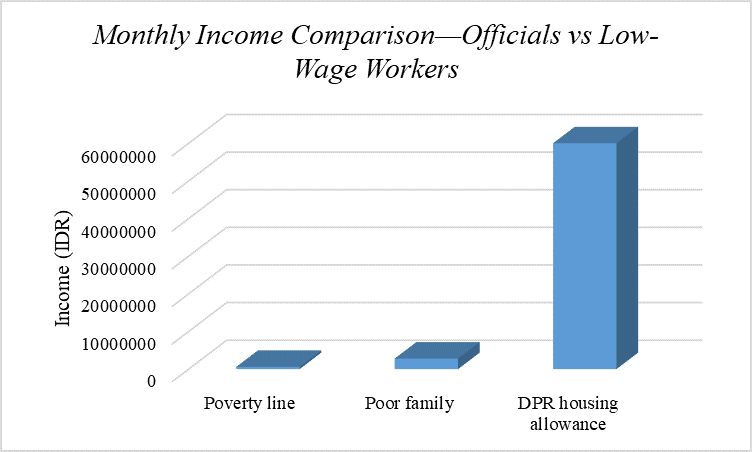

Contract teachers highlight the disparity between wages and living expenses. Seventy-four percent of them earn below the local minimum wage; some even receive only IDR 785,000 per month, while the average salary for elementary school teachers is only IDR 1.2 million. This reflects a broader phenomenon of unstable employment—short-term contracts, low wages, and minimal protections—that dominates Indonesia's labor market. The contrast is striking: while members of parliament enjoy a monthly housing allowance of IDR 50 million, the official poverty line remains at IDR 595,242 per capita (BPS, 2024). A family of five living below the poverty line survives on only IDR 2.8 million per month. This imbalance reflects what relative deprivation theory predicts: as inequality becomes more visible, grievances deepen and mobilization spreads (Gurr, 1970).

Visual 2: Monthly Income Comparison—Officials vs Low-Wage Workers

Source: Statistics Indonesia (BPS), 2025

Who Is Protesting?

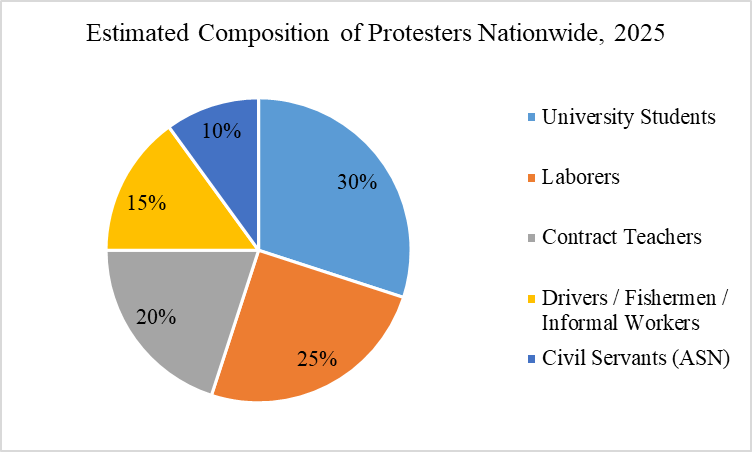

Unlike previous waves of unrest, which were dominated by students or organized labor unions, the current demonstrations involve almost all segments of society. The #IndonesiaGelap movement, led by the Indonesian Student Executive Board Alliance (BEM SI), successfully mobilized around 5,000 students in February 2025. In Pati, the scale of the demonstrations was much larger, with 85,000–100,000 participants taking part in protests in August. Demonstration participants now include contract teachers, fishermen, truck drivers, civil servants, and online motorcycle taxi drivers.

Charles Tilly's (2004) work on social movements notes that when grievances unite, the “repertoire of resistance” expands across social groups. The current demonstrations in Indonesia demonstrate this: the transformation of economic pressure into cross-class mass mobilization and widespread financial insecurity.

Visual 3: Estimated Composition of Protesters Nationwide, 2025

Source: Compiled from media reports & protest estimates (2025)

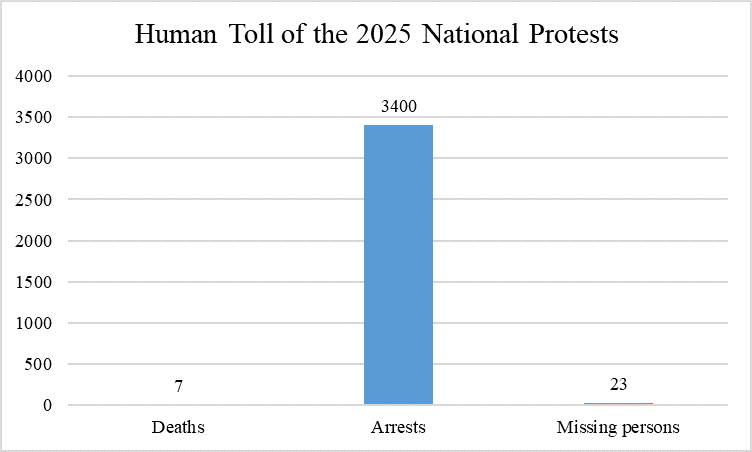

The Social and Political Toll

The demonstrations were not peaceful. In Pati, a viral video showed a protester being killed by a police water cannon, sparking nationwide outrage. During August 2025, at least seven protesters were killed, more than 3,400 were arrested, and around 20–23 people are still missing. This escalation illustrates what Della Porta & Tarrow (2012) describe as the radicalization of conflict—when state repression intensifies rather than defusing protest activity.

The riots also shook economic stability. The Jakarta Composite Index (IHSG) fell 2.27% over the week, while the rupiah weakened by nearly 1%, prompting Bank Indonesia to intervene. Such volatility signaled that social discontent was no longer solely a domestic issue but had turned into a broader political and market risk.

Visual 4: Impact of the 2025 National Protests—Human Toll of the 2025 National Protests

Source: Compiled from Tempo and AP News (2025).

Implications for Indonesia’s Stability

The convergence of food insecurity, wage stagnation, and inequality underscores structural fragilities in Indonesia’s development model. As Snow & Soule (2010) argue, movements escalate when everyday grievances align with perceptions of systemic injustice. Indonesia is reaching a critical inflection point: protests are not only about food prices, but also about fairness, dignity, and representation.

The government’s response—primarily deploying additional security forces—risks deepening mistrust and eroding the legitimacy of governance. If unchecked, unrest threatens not only political stability but also investor confidence. The challenge is thus dual: to manage short-term economic pain while implementing deeper reforms to reduce inequality and rebuild public trust.

Policy Recommendations: Dialogue, Not Repression

Responding with violence alone is ineffective. Instead:

- Stabilize food prices by strengthening domestic supply chains, reducing dependence on imports, and implementing targeted subsidies.

- Improve working conditions by expanding social protection, enforcing fair wages, and transitioning contract workers to safer jobs.

- Address inequality by rationalizing parliamentary allowances and redirecting fiscal resources to welfare programs and social investment.

- Institutionalize mechanisms for dialogue between the government and civil society, reduce dependence on repressive law enforcement, and build trust through participatory governance.

Only through economic justice and empathetic governance can Indonesia alleviate the current crisis.

Conclusion

Indonesia’s protests are not spontaneous flare-ups but the outcome of structural economic pressures, inequality, and disillusionment with the state. The unrest underscores that social stability cannot be purchased by repression alone—it requires justice, dialogue, and reform. As long as these root causes remain unaddressed, unrest will persist. The question is not why people protest—but why they feel compelled to do so.

References

Badan Pusat Statistik. (2024). Statistical Yearbook of Indonesia 2024. Jakarta: BPS.

Bank Indonesia. (2025). Monetary policy review, August 2025. Jakarta: BI.

Della Porta, D., & Tarrow, S. (2012). Interactive diffusion: The transnational spread of protest. European Political Science Review, 4(2), 163–189.

Gurr, T. R. (1970). Why men rebel. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Snow, D. A., & Soule, S. A. (2010). A primer on social movements. New York: W. W. Norton.

Tilly, C. (2004). Social movements, 1768–2004. Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

World Bank. (2025). Indonesia economic prospects: Navigating rising prices. Jakarta: World Bank.

Fatin Fadhilah Hasib

Fatin Fadhilah Hasib is a lecturer at the Department of Islamic Economics, Universitas Airlangga. Her academic focus covers Islamic strategic management and entrepreneurship, Islamic risk management, and Islamic marketing management....

Fatin Fadhilah Hasib

Fatin Fadhilah Hasib