The contemporary artist faces a number of choices when using a particular medium- the traditional plastic arts found in most art schools such as oil or acrylic painting, printmaking, stone or ceramic sculpture; the photographic-based arts and electronic media that mixes video and installation; and finally the classical traditions related to craft that tend to resurface every few years and can encompass a disparate range of methods of making paper (Japan), natural ingredients (Mexico) and/or using ink and calligraphic styles (Türkiye). The almost limitless sources of information and inspiration, which are a part of the over-saturated and hurried post-modern life can become overwhelming for both the artist to find the correct platform and for the viewer to distinguish between pastiche, derivative craft and innovative original work. If we were to add the more recent emphasis on identity-politics against the dominant slant of eurocentrism that runs through the history of art and many would dismiss contemporary art as antithesis to Islamic art and its emphasis on the sacred- the reality is both more complex and potentially ground-breaking for new movements that are original, use new media and work within certain traditions.

In Türkiye, over the last decade and a half there has been an explosion of renewed interest in “classical” Ottoman architecture (something that was not even taught in architecture programs for most of the history of the Republic) as well as ornately framed Qur’anic verses in calligraphy and Hilye-i Şerif (calligraphic features of the Prophet Muhammed); in film/TV, there have been numerous productions of historical Ottoman dramas as well as more independent films with contemporary Muslim characters (a major theme with the latter continues to be rural/urban cultural and lifestyle divisions). All of these speak to a longing to reconnect with a cultural legacy that is considered a high point in the history of Islamic art. It also speaks to the misguided problem of content, style and what defines Art. The big-budget mosques, high-brow collectors and slick TV series as well as the less-refined calligraphy and lower budget films all have one thing in common: a very narrow interpretation of Islamic art that often conflates reproduction (mosques), content (calligraphy) and historical style and/or history (TV/cinema) with producing art. At the other end of the spectrum, the “global” contemporary art scene places Istanbul as one of its stops with no reference to any of the areas previously mentioned; it is as if the two inhabit completely different worlds where the term “contemporary art” refers to work that is driven solely by the post-modern dictates of numerous social topics with a deliberate exclusion of anything related to Ottoman or Islamic history/culture (Rahman, 2016).

Islamic Art and Modernism

Islamic art is a very broad term that describes a multitude of styles and mediums throughout the world. Historical dynasties such as Ottoman, Persian, Mughal and Deccani have produced numerous works of lasting significance in both architecture and painting (as well as sculptural objects, calligraphic works etc.). An examination of formal qualities shows an emphasis on the use of space and light (architecture) as well as color and line (both within architecture and in miniature painting) to represent which is unrepresentable; a meaningful expression of the vastness/infinity of the heavens and the splendor of creation. This is in fact a modernist approach to art where abstraction and a non-naturalistic approach leads to a fresh yet, sophisticated interaction; variations on patterns found in nature and the dichotomy of minimalist/maximalist form alongside vibrant colors and innovatory use of light are among the reasons Islamic art from these periods still feels relevant and ultramodern. It is reproduced in contemporary design and furniture; and previously served as an inspiration for numerous figures in European art history. While the advent of Western modernism in painting is usually conferred to the late 19th and early 20th centuries and architecture is placed in early to mid-20th century- an alternative reading can situate the advent of modernism with these expressions in Islamic art from much earlier centuries (Rahman, 2017).

Kaz Rahman depicts Istanbul during the 15 July coup attempt in his work “Black Dogs”.

Craft, Concept and Formalism

Many of the debates between what is considered “art” can be broken down into the difference between the craft of what is being made and the overall idea/theme/concept. Ideally, they work in tandem where an idea or concept is strong, original, and thought-provoking, and the execution of the work is at a high level of craftsmanship. This can also hold true when discussing works of cinema where a story that is of a highly original level should be matched with audio/visual expression that makes the concept and themes resound more. Separating “technical” crafts in any medium with those who are only concerned with “ideas” is a foolhardy practice; the great works in any medium show the artist in command of certain technical areas while also working with other craftspeople who are even more specialist- consider traditional Ottoman painting workshops with the lead artist and several assistants working under him, the role of the architect and the number of specialist craftspeople or the role of filmmaker and the sometimes hundreds of cast and crew members. In all of these cases the artist, architect or film director is versed in the fundamentals of craft but cannot do everything alone; at the same time one should not confuse knowing a craft with the ability to make art, architecture or cinema. An idea is needed and in contemporary work, that concept should have something to say- whether it is a commentary on past works/traditions, societies or something more sacred. Here again one should not confuse having an idea with the ability to make art, architecture or cinema… The bridge between the world of craft and concept is the formal language of the medium(s); and that is the important third area of experience and innovation which distinguishes the ability of the artist (whatever the medium- architecture, film or traditional mediums). There is huge area of “doing” that is needed in order to understand the medium, its possibilities and how to take a work into new and original territory.

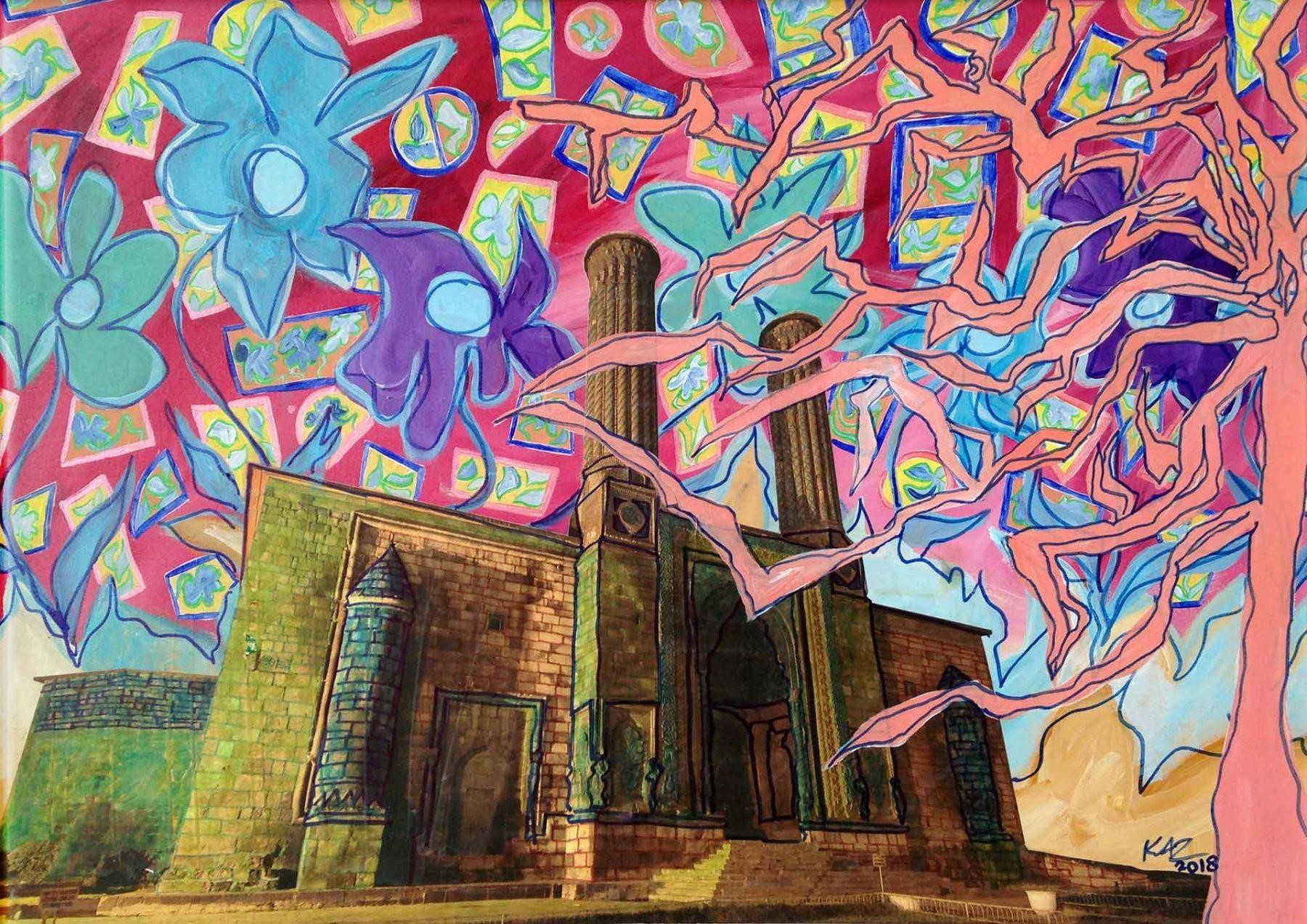

Kaz Rahman, “Seljuk Landscape”, 2018.

Towards an Avant-Garde

One of the biggest challenges in presenting a comprehensive movement in contemporary Islamic art is the fragmentary nature of both the mediums being used and the spaces/galleries promoting the work. Some artists showing in London, New York and the Gulf states have not explicitly framed the work within “Islamic Art”, while others have co-opted the term when making work related to social justice or identity politics that has little to do with the formal qualities related to Islamic art. Architecture provides the work of a towering figure such as Zaha Hadid (1950-2016), committed to modernism and fragmented geometric forms/patterns while never explicitly having been placed within an Islamic art tradition. Iran continues to cast a long shadow in terms of painting, drawing and mixed media, while the cinematic Iranian New Wave of the 1990’s led by Abbas Kiarostami (1940-2016) continues to be a major breakthrough and inspiration for many artists and filmmakers around the world. Projects like Firoza[1] and the Jameel Prize[2] are aimed at curating works related to contemporary Islamic art with the latter having shown several artists working out of Iran, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Algeria and Turkey. Islamic Arts with a plural may be a more apt description going forward since there is a burgeoning of work over the last several decades related to performance, poetry, music and electroacoustic arts that is also interconnected with both tradition and the avant-garde.[3]

References

Rahman, K. (2016). Istanbul and contemporary Islamic art. Retrieved from: https://politicstoday.org/istanbul-and-contemporary-islamic-art/

Rahman, K. (2017). Islamic art and modernism: Formal elements in painting, architecture and film. Istanbul/Rome: New East Foundation.

[1] See: https://www.firoza.co.uk/