Turkey has a significant migration history, as it has served as both a destination and a transit country. Being located in a central position in the world where migration has become a global issue, Türkiye has been receiving migration from different countries such as Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, and Iran for years, each with varying degrees of intensity and at different times. At this point, Afghanistan stands out with its half-century-long migration history and the increasing migration intensity in recent years.

Afghanistan is one of the leading countries of origin for migrants in the world because of the invasions, wars, civil unrest, economic crises, and poverty ongoing for years. As of 2022, there are 26.4 million refugees globally. While five countries account for 68% of refugees, Afghanistan ranks third with 2.6 million refugees (McAuliffe & Triandafyllidou, 2021, p. 46). However, it should be kept in mind that Afghanistan was the world’s largest country of origin for refugees until the Syrian Civil War. While these statistics indicate the scale of migration from Afghanistan, it would be misleading to look at the situation solely from a present-day perspective.

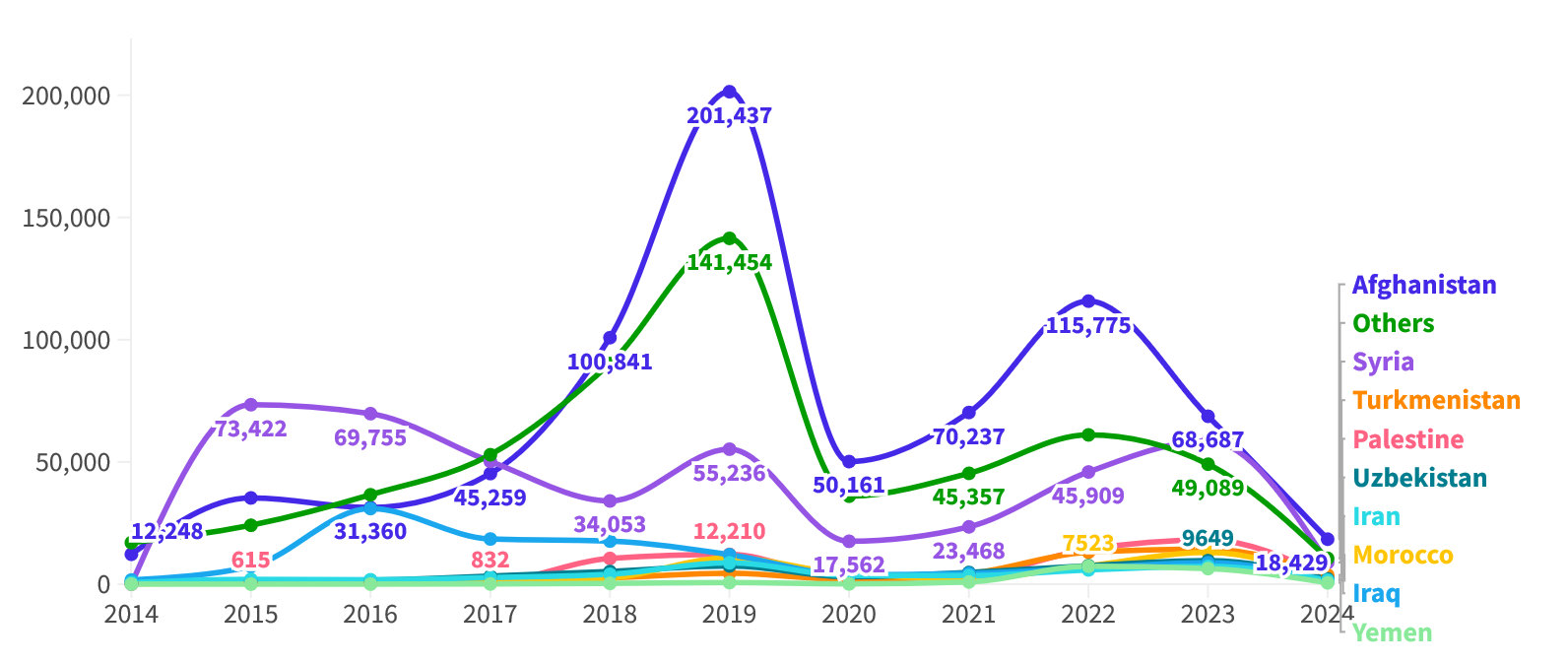

While migration from Afghanistan to Türkiye has a history of around 40 years, there has been a significant increase in the number of migrants coming through the Afghanistan-Pakistan-Iran corridor, especially in recent years. However, it is not possible to clearly indicate this increase with figures. The public data on irregular migration to Turkey by the Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Interior Presidency of Migration Management (GİB), the primary official institution in Turkey on migration, is limited. On the other hand, the GİB regularly shares other indirect data that help to reveal the intensity of migration. The number of Afghan migrants caught in just 2018 and 2019 exceeded 300,000, accounting for almost half of the total irregular migrants caught during those two years combined. Moreover, when examining the distribution of nationalities among irregular migrants caught from 2018 to the present, it’s observed that Afghan nationals are the most frequently caught irregular migrants every year (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Interior Presidency of Migration Management, 2024).

While migration from Afghanistan to Türkiye has a history of around 40 years, there has been a significant increase in the number of migrants coming through the Afghanistan-Pakistan-Iran corridor

Figure 1. Distribution of Irregular Migrants by Citizenship by Year (By 21.03.2024)

Source: Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Interior Presidency of Migration Management

An Unavoidable Stopover for Migrants from Afghanistan: Van

The Turkey-Iran border spans 534 kilometers, with 295 kilometers located in Van. Therefore, Van has been an unavoidable stopover for migrants from Afghanistan who aim to cross into Turkey or European countries via Turkey for decades. For this reason, I have conducted field research regularly in the city center, districts, and border villages of Van since 2021. The memory of half of a century of migration in the city has become prominent when we examine the migration process from the perspective of local actors (Ünay, 2022). Also, especially in recent years, the increasing intensity has led Türkiye to structure its migration policies in a security-centered form. Policies have been implemented to prevent migrants from entering the country through the Iran border, similar to those at the Syria and Iraq borders along the migration route. Hence, Türkiye’s wall policy, which aligns with global trends, has also been implemented along the Iranian border. Türkiye is building a 295-kilometer wall along its border with Iran that passes through Van. While strengthening the wall with technological equipment, Turkey has also significantly integrated law enforcement into the wall, particularly after 2021.

From the Field: Current Developments

During the summer of 2021, images circulating on social media and various media outlets, often depicted as a “flood of migrants coming to Türkiye,” were in the spotlight for a long time. In the field research I conducted during this period, especially in interviews with villagers, although some stated that there were predominantly young male migrants, there were also women and children migrants. In this regard, the methods of smugglers for smuggling migrants across borders are important as the images shared with the public are closely related to this. Smugglers separate young men, women, and children into separate groups during border crossings to speed up the process for each group and reduce the risk of being captured by authorities. That’s why there were more young male migrants compared to other groups reflected in those images. Hence, while it is true that young men are predominant among Afghan migrants, it would be a misconception to say that only young men are crossing the border. Another misconception is that the migrant density increased radically in the summer of 2021. In fact, there has been a similar density of migrants crossing the border for nearly 40 years, and if there is an increase, it has been observed as of 2018.

Source: BBC News

During my interviews in Van, I learned that around 1200-1500 migrants cross the border daily, and it can be argued that migrants cross the border, particularly at high rates in July and August. According to the information I got from villagers, the number of migrants has reached twice the population of the villages. Although there was a decrease after the publicity of migration, daily migrant crossings were around 800-900, even in October. On the other hand, although the number of crossings decreased even further due to the harsh winter conditions, around 300-500 migrants crossed into Türkiye daily, according to my interviews in January. Migrants from Afghanistan generally leave their country due to the danger posed by the Taliban and the poor economic conditions in Afghanistan. While the smugglers determine the routes of the migrants, according to my interviews, a migrant from Afghanistan is on the road for 18-20 days on average, and this period can be shorter or longer depending on the conditions. While much attention has been given to the number of migrants arriving from Afghanistan to Türkiye, it is known that dozens of migrants have lost their lives due to freezing in harsh winter conditions (Ünay, 2022).

A migrant from Afghanistan is on the road for 18-20 days on average, and this period can be shorter or longer depending on the conditions.

All these challenging processes stem from the nature of migration and the migration route in question. In addition, the implementation of increased security measures at the Iran and Turkey borders, the routine use of pushback practices that violate human rights, the harsh treatment of migrants by border officials, and the growth of bandits and kidnappers in recent years have all worsened the process for migrants. On the other hand, the cost of the Afghanistan-Türkiye (Van) route, which was around $1500-$2000 in 2020, has now reached up to $5000[1]. In exchange for this fee, migrant smugglers usually allow migrants to cross the border up to three times. However, the recent radical increase in pushback and deportation practices results in far more pushback than this number, making border crossings significantly more difficult for migrants and often causing the money they paid to smugglers to go to waste.

Suggestions for the Future of Migration to Türkiye from Afghanistan

Despite all these difficulties and the increase in security measures, it would be quite wrong to assume that migration from Afghanistan to Türkiye will decrease, pause, or end, and this misconception stems from the lack of sufficient knowledge and understanding of migration and migrants. Aside from a 40-year-long migration history, there is a similar continuity in all migration processes around the world, regardless of the obstacles. Indeed, the cliché that migration dates back as far as human history itself, which has become a cliché subject to criticism, embodies this misconception. From this point of view, it has become an obligation to make some humble suggestions regarding migration from Afghanistan to Türkiye:

- Türkiye should aim to handle migration not only from a security standpoint but also from a broader perspective.

- While ensuring border security, these security policies should not lead to practices that violate the human rights of migrants.

- The idea of building walls at borders to prevent migrants is an absurd practice that should be abandoned immediately. In the field, it has been observed firsthand that walls can be easily overcome with a ladder higher than the wall, a tunnel that can be dug, or a blanket thrown over barbed wires. Border walls could only contribute to changes in migration routes and lead migrants to longer and more dangerous paths, which increases the risk of life-threatening situations for migrants.

- The recent radical increase in pushback and deportation practices at the borders should be abandoned. The legal process of deporting migrants should not be disregarded, and efforts should be made to prevent human rights violations and not normalize such violations.

- Humanitarian diplomacy should be reconsidered as the primary focus of migration policies. And these migration policies should prioritize addressing the root causes of migration in countries of origin.

- Migrants should not be used as a tool of domestic or foreign policies.

References

Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Interior Presidency of Migration Management. (March, 2024). Distribution of Irregular Migrants by Citizenship by Year. Retrieved from https://www.goc.gov.tr/duzensiz-goc-istatistikler

McAuliffe, M., & Triandafyllidou, A. (2021). World migration report 2022. International Organization for Migration. Retrieved from https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789292680763

Qurbani, S. (2023). Afghan migrants kidnapped and tortured on Iran-Turkey border. BBC. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-65749889

Ünay, H. (2022). Türkiye’ye yönelik Afganistan göçüne yerelden bakmak: Van saha araştırması çalışma raporu. Göç Araştırmaları Vakfı. Retrieved from https://gocvakfi.org/calisma-raporlari/

[1] The data is based on the author’s field research called “Decentring the Study of Migrant Returns and Readmission Policies in Europe and Beyond (GAPs)” for the Horizon project in Van in January 2024. For the further information, see https://www.returnmigration.eu/