Against a background of debates and opposition to the juxtaposition of the concepts of Islam and feminism, Islamic feminism tries to explain itself from a different perspective. At the same time, the concept of Islamic feminism contains many dilemmas that have not been fully clarified in the literature (Tohidi, 2004, p. 282). Although there are those who reject this idea because it constitutes an orientalist perspective, Islamic feminism became visible in the 1990s (Bora, 2008, p.65). Muslim women, who are defined by their religion through this idea, led by educated conservative women, have tried to demonstrate their feminist stance through Islam as well as for Islam (Ali, 2019, p.16). While some of these women do not hesitate to identify themselves as Muslim feminists, they are hesitant to use the term Islamic feminism, which has been adopted as an ideology. While writers such as Egyptian Nawwal al-Saadawi and Moroccan Fatima Mernissi write on Islamic feminism and support studies in this field, they refrain from defining themselves as “Islamic feminists”. On the contrary, writers such as Magrod Badron state that every woman who lives in a Muslim country and identifies herself as Muslim actually contributes to Islamic feminism and works to produce this discourse (Güç, 2008, p. 656).

Feminism and Islam

Although the idea of Islamic feminism was introduced as a term in the 1990s, many Muslim feminist women trace their rejection of male domination in the Muslim society back to the emergence of Islam (Ali, 2019, p. 17). At the same time, there is a consensus that feminism did not appear before or after feminist thought, but rather around the same time (Ali. 2019, p. 19). Islamic feminists agree that Islamic sources should be read through women and reinterpreted in favour of women. Women desire a system that allows them to advance in their national, ethnic, and cultural identities without ignoring them at the same time, and they do not want to compromise their religious sensitivities (Tohidi, 2004, p. 280).

For women living in a Muslim country, embracing feminism was in part a response to the traditional patriarchal ideas of a religious authority, and Muslim feminists sought to reform these traditional elements. At the same time, in response to the perception of modernity and secularism proposed by feminism, these women have endeavoured to hold fast unto religion in their lives. As a result of all this, it is possible to state the following: Muslim feminists are struggling internally with the traditional patriarchal order and externally with the dilemmas of modern ideas and seeking a religion-based answer (Tohidi, 2004, p. 285).

The notion of feminism is not a monolithically precise phenomenon that carries certain widely held presumptions. It is possible to categorize it differently according to its extent. For example, some feminists believe in the basic teachings of the Qur’an and reject issues such as polygamy and inheritance as ancient Arab traditions. On the other hand, some Islamic feminists, while accepting the teachings of the Qur’an to the latter, argue that the Qur’an appears to draw strong boundaries for women because it is interpreted with a male monopoly and that it should be reinterpreted in favour of women. (Gürhan, 2011, p. 114) The pioneer of this has been the Sisters in Islam (SIS) group operating in Malaysia. Along with the groups that prioritize feminism and work for the reinterpretation of the Qur’an in favour of women, the idea that the main factor in the occurrence of violence against women is not the main source of Islam but traditional teachings has become more accepted. Many Islamic feminists who advocate this view have developed themselves in the field of Qur’anic exegesis and hadith and produced contemporary methods (Güç, 2008, p. 659). Islamic feminists can be divided into three main groups: traditional reformists, who accept that Islam grants women and men “equal” rights and duties and even if not equal, exalts their status in granting them pivotal family positions like mother, sister and wife; radical reformists, who, while accept the need to stick to primary religious sources, question their patriarchal interpretations about women’s roles in society; liberal feminists who, despite identifying themselves as Muslims and adhering to the Qur’an and Sunnah, argue that the Qur’an does not require jurisprudence and should be evaluated subjectively and that patriarchal discourses should be evaluated in the traditional context (Ali, 2019, p. 31 ).

Islamic Feminism in the Muslim World

While there are many interpretations of the term Islamic feminism, it is difficult to conduct a detailed analysis of women’s thoughts on Islamic feminism and their participation rates in the Middle East. In addition, there are debates on whether women’s reactions to problems within a country or their struggles for their rights and freedoms could also be seen as feminist actions. However, it is also possible to say that feminist movements are ideas that emerged after women’s movements (Ertan and Dikme, 2016, p. 80).

The concept of Islamic feminism was first used in Iran by Iranians, Afsaneh Najmabadeh and Ziba Mir-Hosseini in the magazine Zanan, founded by Shahla Sherkat; while in Türkiye, it appeared in Nilüfer Göle’s book Modern Mahrem in 1991. In Arabia in 1996, it was mentioned by Mai Yamani in her book Feminism and Islam, and again in the 1990s, African activist Shamima Shaikh used the term “Islamic feminist” (Ali, 2019, p. 40).

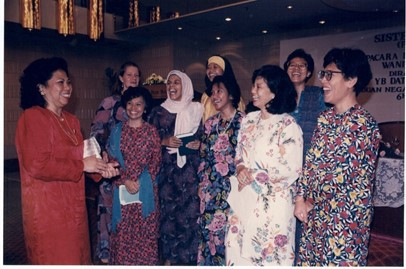

Women engaged in Islamic feminist work have mostly coalesced around the Iranian magazine Zanan and Sister in Islam (SIS), which is very active in Malaysia. Founded in Malaysia in the late 1980s by Zainah Anwar, SIS has been active in the reinterpretation of the Qur’an and Hadith. The Iranian journals Payam-e Hajar, Zanan and Farzaneh: Journal of Women’s Studies and Research have contributed greatly to the expansion of Islamic feminist discourses. By 2000, the magazine Swara Rahima, published by the Rahime Foundation in Indonesia, the feminist movement led by Esma al-Murabit in Morocco, the Iraqi Islamist Feminist Movement in Iraq, the New Women’s Foundation, the Arab Women’s Solidarity Foundation, and many other organizations and movements had taken on the role of the continuity of Islamic feminism (Gürhan, 2010, p. 372).

Malaysia Sisters in Islam (SIS)

In order to define the arguments for Islamic feminism, figures such as Amina Wadud, Riffat Hassan or Fatima Naseef have focused on the Qur’an and its different tasfseers. Similarly, Shaheen Sardar Ali from Pakistan and Aziza Al-Hibri from Lebanon compare their understanding of the Qur’an with different Sharia practices. Fatima Mennisi from Morocco and Turkish writer Hidayet Tuksal try to reinterpret hadiths (Ali, 2019, p. 45). In addition to these, Kasım Emin’s Tahrir’ül- Mer’e in Egypt in 1990 paved the way for the emergence of the idea of feminism in Muslim countries and set an example for later works. This Islamic feminism that emerged in Egypt has three main features. First, it is a Qur’an-based approach; second, it sharpens the line between East and West by giving importance to Islamic traditions and culture; and finally, it considers the family as a social institution. Although there are some exceptions, Islamic feminist thinkers in Egypt have not been much influenced by Western ideologies; they have continued on their journey in different ways, with more traditional and cultural acceptances (Güç, 2008, p.660).

Islamic Feminism in Iran

In Iran, the 1979 Islamic revolution unexpectedly created a relationship between Islamic law and feminism. In such an environment, women who lead a religious life but opposed the presuppositions of traditional beliefs were provided with an opportunity to claim their rights and “Islamic feminism” emerged as a solution (Ali, 2019, p.107). However, Islamic feminism in Iran has not been an idea that blends its own traditional elements as in Egypt. On the contrary, it has been highly influenced by secular feminist ideas from the West. Afsanah Najmabadi, who coined the term Islamic feminism in Iran – and around the world – in a speech in 1994, considered Islamic feminism as a movement that made dialogue with secular feminism in the West possible. Many women writers working for Zanan magazine[1] also recognized that they shared common grounds with feminists who espouse secular ideas (Güç, 2008, p.661).

It is known that Shirin Ebadi, an Iranian judge who considers herself as a religious and culturally devoted individual, has been in a great dilemma after the rights she lost with the revolution and has stood against the mandatory wearing of headscarf restriction, stating that the revolution was the murderer of her daughters (Ebadi, 2008). In addition, in an interview in 1999, Ebadi put forward the general understanding of Islamic feminism in Iran as follows (Tohidi, 2004, p. 282):

If Islamic feminism means that a Muslim woman can also be a feminist and that feminism and Islam are not irreconcilable, I agree with it. However, if this implies that feminism in Muslim communities is somehow unique and fundamentally distinct from feminisms in other societies, then I disagree with the idea that it must always be Islamic.

The existence of such examples is quite common among Iranian feminist thinkers. Taking these into account, some authors emphasize that although Iranian and Western feminists oppose Eurocentric approaches, many of their discourses follow an orientalist approach (Güç, 2008, p. 665).

The Zanan magazine banned in Iran.

On the contrary, pro-revolutionary women such as Jamile Kadivar, a proponent of Islamic feminism in Iran, emphasized that Khomeini’s revelations on the women’s issue were not fully understood, stating that the revolution transformed women from being a commodity and an object into their own identity and freed them from the “wrong understanding of freedom”. Thus, according to Kadivar, Islamic feminist understanding can only be achieved by being fully committed to traditions and Islam and reading the sources properly with an Islamic understanding (Kadivar, 2014, p. 63).

Alternative Perspectives on Feminism

Many feminist thinkers underline that religions are fundamentally a part of patriarchal discourse and that it is quite wrong for women to express their feminine discourse within a religious framework and that it is an acceptance of male dominance hence “a battle lost from the beginning”. They also criticize the work of civil society organizations such as Sisters in Islam, the most important actor of Islamic feminist work in Malaysia. In contrast, Malaysian writer Zainah Anwar underlines that activists working in this field have been working seriously for a long time and have been struggling against the traditional norms. Underlining the emancipation of women through organizations such as Sisters in Islam established in Malaysia, Anwar underlined that these movements are actually based on an Islamic foundation, saying, “We are rediscovering Islam for ourselves, which raised our status by giving us rights that were revolutionary for us 1400 years ago” (Ali, 2019, p. 131).

While Islamic feminists living in places with large Muslim populations are expanding their activities, it is noteworthy that there is almost no participation in such activities in Türkiye. The lack of major structured organizations in Türkiye has affected the continuity of the idea of Islamic feminism. In addition to names such as Cihan Aktaş, Sibel Eraslan, Nazife Şişman, Yıldız Ramazanoğlu, Hidayet Şefkatli and Mualla Gülnaz, who have distanced themselves from the concept of Islamic feminism, have contributed to studies on Islamic feminism and Muslim feminists in Türkiye. In addition to this, it can be said that women who pursue feminism movements along Islamic lines and women who follow a secular line in Türkiye do not act together hence do not form a collective movement. The claims of secular feminists that women who choose to wear the headscarf are serving patriarchy are refuted by these women with the argument that the cover with themselves with their free will and to abide by their religion. The bipolar understanding of feminism in Türkiye has turned into a political discourse as well (Altıparmak and Budak, 2020, p.34).

Conclusion

The idea of Islamic feminism, which emerged as a result of Muslim women’s attempts to gain their individual identity, remains to be a growing ideology worldwide. It brings along problems in many areas such as the reinterpretation of Qur’an prioritizing women, the classification of unauthentic hadiths, and the rejection of traditional assumptions, especially the debate on whether it is an extension of Western-based feminism. This idea, which has expanded its sphere of influence in many countries, especially in Iran, has found different responses depending on the country. Islamic feminism, the foundations of which were established with the Zanan magazine, is now moving towards being replaced by more secular initiatives in Iran. The recent Mahsa Amini protests in Iran can also be considered a secular movement. In addition to all of these, it is not possible to make precise analyses about the prevalence of Islamic feminism in the Middle East. It would be better to view these judgments via a perspective of women’s movements and to interpret them in light of their various facets.

References

Aksu, B. (2008). Women’s movement in the Middle East: Different paths, different strategies. Istanbul University. Journal of the Faculty of Political Sciences, 39, 55-59.

Ali, Z. (2019). Islamic feminisms. Istanbul: İletişim Publications.

Altıparmak Ş. and Budak H. (2020). Islamic feminism and its reflections in Türkiye. Karatay Journal of Social Research, 4, 21-41.

Ertan, S. Dikme and R. (2016). The impact of the Arab Spring on women’s rights. TESAM Academy Journal, 3(2), 73-108.

Güç, A. (2008). Islamist feminism: Muslim women’s efforts to become individuals. Journal of Uludag University Faculty of Theology, 17 (2), 649-673.

Gürgan, N. (2011). An attempt to reread the Qur’an from a woman’s perspective Amina Wedud Qur’an and women. Journal of Oriental Studies, 6, 112-124.

Kadivar, C. (2014). Zen. Istanbul: Mana Publications.

Nayerehi T. (2004) “Islamic feminism: dangers and promising elements”. Journal of Ankara University Faculty of Theology, 11, 279-289.

[1] The magazine was shut down by the Iranian state in 2008.