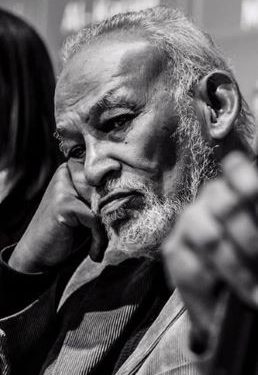

Born in Sudan in 1932, Malik Badri was a Muslim social scientist and psychologist. When talking about Badri, the emphasis on his professional and religious identity is quite essential because he was trying and aiming to integrate his profession and religion throughout his life. We can see this scientific and spiritual revolution, to which he devoted himself professionally and religiously, under two headings: Indigenous psychology and the Islamization of psychology.

Indigenous psychology

In the early years of his career, Badri emphasized the lack of cultural sensitivity in Western psychology theories and revealed that scientific scales were formed with Western prejudices and that the results were biased because of this (Badri, 1963). In this context, he developed the IQ test questions, which he claims were created for Westerners, by adapting them to Sudanese culture. Similarly, he redesigned the drawing tests to make them suitable for use with Sudanese children and later expanded it to Arab children generally (Badri, 1966). Afterwards, Badri continued his research on the psychological and sociological effects of other cultural elements (idioms, customs) and emphasized that indigenous practices should be handled, researched and analyzed within their cultural context and opposed the psychopathological evaluation of cultural practices (Badri, 1966; 1972).

Badri tried to meet the need for indigenousness, which he supported with his research, at the academic level by developing an Islamic perspective psychology curriculum for different Arab universities and by working on traditional folkloric psychotherapy treatments (Badri, 1972). In his lessons and the curricula he developed, Badri gave importance to learning Western psychology theories and then criticizing them. Because, according to Badri, it is possible to criticize these theories only by knowing them very well (Badri, 2018b). In this way, he wanted his students and psychologists to see how these theories clashed with indigenous and Islamic beliefs. Thus, for psychology, Malik Badri followed a method that can be expressed as indigenousness in general and “bottom-up” for Islamization in particular. In this approach, existing Western theories and methods are tried to be adapted to the indigenous and cultural context.

In fact, indigenous psychology is not an idea unique to Malik Badri. The “indigenous psychology movement”, which began to rise in the 1970s, drew attention to the cultural insensitivity of Western psychology. Objections to the universality claim of psychology have emerged from within the Western psychology itself, which Bedri criticizes, and demands for indigenousness have been made. Eastern as well as Western scholars have called for a indigenous and cultural psychology (Moghaddam, 1987; Misra, 1996; Sloan, 1996). Although these calls are justified, it is natural that every science and its related concepts and theories bear the traces of the culture in which they were born. Therefore, since psychology is a discipline that is systematized and defined in the West, it bears the paradigm, philosophy and even religious traces of the period and environment in which it emerged. In this respect, “every psychology is indigenous psychology” (see Marsella, 2013). The problem is the claims of universality with the reductionist attitude of Western psychology. Western psychology cannot be seen as the only valid psychology and “other psychologies” hence cannot be invalidated. What if psychology had developed (named) in another culture rather than in the West? Considering the reasons and necessity of “Islamic Psychology”, one should ask that if psychology was born and raised in the Islamic world, would it still be called Islamic psychology?

Islamization of psychology

Malik Badri, at the inaugural congress of the International Association of Islamic Psychology (IAIP) in Istanbul in 2018, said, “If someone told me in those years (1975-1979) that ‘One day you will come and sit next to people of the same opinion at an Islamic psychology congress,’ I would say that ‘What is he talking about? He must have gone mad’.” He had obviously waited and worked for many years for this moment. So what made Malik Badri say these words?

Although Malik Badri is known as the “father of Islamic psychology” today, he did not earn this title easily. He dedicated his book, The Dilemma of Muslim Psychologists, which he wrote in 1979, “to Muslim pioneers who broke the chains of mental bondage against the theories of the West and their applications in the social sciences. Also, from new Muslim psychologists and psychiatrists, who have devoted their careers to laying the foundations of Islamic Psychology”. By doing so he was satirizing the Muslim psychologists he addressed many years ago. The main idea of his work, The Dilemma of Muslim Psychologists, was based on Badri’s speech titled “Muslim Psychologists in the Lizard’s Hole” at the conference of the Association of Muslim Social Scientists in 1975. In his speech, Badri criticized the Muslim psychologists of his time and in return drew their reactions. In this speech and in his later article, Badri discussed and criticized “the dangers of unconscious (Western) copying among Muslim psychologists” based on the hadith “If they go into a lizard hole, you will follow them” (Badri, 2018, p.12). This criticism, on the other hand, disturbed Muslim psychologists who had returned to their countries after studying in the West, adopting the psychology and science understanding of that region, because they opposed the idea of including religion in psychology, which is an original scientific discipline, and even Islamizing it, saying: Is there a sinful physique or non-Islamic chemistry and you are talking about an Islamic psychology? If you do not accept Freudian psychoanalysis, show us a better way to treat emotional disorders.” (Khan, 2021, p. 141). This is how Malik Badri seems to have sought for the Islamization of psychology throughout his life.

In the 1950s, when he was still a university student, Badri developed reactions to the “Americanization” activities and started to seek Islamic answers to secular problems. In his own words, these were his “first Islamization efforts” (Khan, 2021, p. 141). In fact, Badri’s contribution to the Islamization of psychology is an extension of the Islamization of knowledge movement of the 1970s and 1980s. Influenced by names such as Qutb and Mawdudi, Badri had strong reactions to Western psychology in general and psychoanalysis and behaviorism in particular. The core of his critique was on the epistemology of Western psychology and the materialistic philosophy on which it was founded. What he objected to was that Western psychology basically rejected or ignored the religious/spiritual or, in short, the soul of man. In particular, he criticizes Freud’s “absurd claims that base all forms of normal and abnormal behavior on subconscious sexual impulses” (Khan, 2021, p. 140). He thought that the “theory and practice of Rogers’ patient-centered counseling is more ambiguous” (Khan, 2021, p. 140). He found “behavioral therapy that hierarchically guides the patient like a conditioned animal” (Khan, 2021, p. 145) inadequate and rejected it as “directly conflicting with Islamic belief about human nature and spiritual disposition” (Khan, 2021, p. 145). Although he was influenced by names such as Eysenck and Wolpe and applied their theories, Badri continued to criticize strongly the “soullessness” of Western psychology, and its “materialist philosophy”, “atheist-based theories”, “atheist positivist philosophy”, and he considered “its explanations about religious and spiritual processes simple or biased” (Badri, 2018, p.91).

However, this rejection of Western psychology by Muslim psychologists of the time does not seem academically acceptable. Because in the history of modern psychology, psychologists such as James, Allport, Jung, Maslow and schools such as humanistic psychology and transpersonal psychology have also accepted the spiritual/religious aspect of man and his connection with love. In addition, seeing psychology as consisting of psychoanalysis and behaviorism resulted in ignoring post-psychoanalysts (for example, Horney) or individual psychology (Adler), and the differences between schools were ignored, considering all psychology to be a product of Darwin and the theory of evolution. In this respect, a total rejection of Western psychology would be unfair. Especially in the light of the religion/spiritual-sensitive psychology/psychotherapy movement that has developed since the 2000s (see Ağılkaya Şahin, 2018), there is no justification for such an opposition today. The justification can only be seen in the attitude shown against the claims of universality and scientificity of modern psychology. The ethnocentric and reductionist paradigm of Western psychology has also been criticized by Western psychologists (see Ağılkaya Şahin, 2018).

The effects of the Islamization of knowledge movement are clearly seen in Badri’s writings that emerged in the 1970s and after, and anti-Westernism is strongly felt in the titles of the works (Badri, 1973; 1982; 1987; 1996; 1998; 2002; 2008; 2012). Badri’s speeches and writings at that time (and indeed throughout his life) had a great impact, the effects of which continue today. The reason why Badri was so influential can be explained by the Zeitgeist of the period. Because at that time, many Muslims from Arab countries who went to Europe and the USA, received psychology/psychotherapy training and returned to their countries. However, these psychologists were not able to reach large masses of people. An important reason for this was that the treatment methods and targets derived from Western mental health and developed for Westerners did not suit Muslims. The fact that Western psychology not only stood distant from the religion rather considered the religious life as an illness or an obstacle to therapy, was a problem for Muslim psychologists and clients leading and Islamic life. For this reason, these Muslim psychologists needed therapy alternatives that fit both their own and their clients’ identities, because for Muslims, their religion is an integral part of their identity and life (Badri, 2009; Badri, 2018).

In 1997, at a conference at the International Islamic University of Malaysia, Malik Badri’s call for the integration of psychology with Islam finally aroused great international interest and acceptance. His book AIDS Crisis (Badri, 1997), which he published in the same year, also contributed to this. With this work, in which he describes what indigenous and Islamic approaches can offer to the “secular world of global health” (Rothman, Ahmed, Awaad, 2022, p. 206), Badri has received international attention and recognition outside of the Islamic world and psychology. The international recognition and interest in Islamic psychology was most recently crowned with the establishment of the International Association of Islamic Psychology (IAIP) in 2017. The establishment of this association is, in a way, an indication of the emancipation stage that Badri desired for Muslim psychologists.

Bedri’s speech “Muslims in the Lizard Hole” and his work The Dilemma of Muslim Psychologists has led to an international interest in combining Islam and psychology among Muslim psychologists since the late 1970s (Agilkaya Şahin, 2019). This shows that Badri (Badri, 2018) has reached the last stage of admiration, reconciliation and liberation that Muslim psychologists have envisioned for them, and they are now out of the lizard hole. Until the end of his life, Malik Badri continued to contribute to the field of Islamic psychology.

Badri became a spiritual revolutionary by supporting his scientific studies with various works from the Islamic tradition. His Contemplation – An Islamic Psychospiritual Study (2018a) is a deep study of contemplation. Modern psychology takes ancient knowledge and practices from many religious traditions and presents them as miraculous practices that strip them of their sacred and transcendental properties and “repackage” them to lead or protect mental health (Ağılkaya Şahin, 2018). Meditation, catharsis, mindfulness are just some of them. There are many studies, especially in the psychology literature about meditation, and in this literature, contemplation is often expressed with meditation. However, meditation is actually a form of worship in Buddhism and is different from contemplation. Badri (2018a) also explains the differences of Islamic contemplation by explaining that meditation is based on eastern religions and aims to change states of consciousness (see Ağılkaya Şahin, 2020). Accordingly, contemplation comes from Qur’anic advice and aims to seek inner knowledge about God. In his work, Badri compares Islamic contemplation with modern meditation techniques and discusses the benefits of meditation and its relation to contemplation as an Islamic worship. In addition, he explains with examples that Islamic thinkers such as Ibn Qayyim, Belhi, al-Ghazali, Ibn Miskawayh, in the context of contemplation, put forward the present inventions of Western cognitive psychology hundreds of years ago. This work of Badri may be of use to psychotherapists as it provides examples of scientific studies, ideas about the psychology of Islamic thinkers, and information about the psychological importance of Islamic contemplation.

The last work of Badri, which I describe as a Muslim psychologist who strives to add his religion and spirituality to his work, is one of his spiritual heritage. In this work, which deals with the emotional aspects of the prophets, he examines the moods and emotions of the Prophets Muhammad (pbuh), Moses and Joseph (Badri, 2021). In this work, Badri investigates the emotional worlds of the Prophets based on the stories of the Prophets in the Qur’an and tries to present the information he gained as a source of inspiration for our own emotional experiences and conflicts. This book, which he managed to complete shortly before his death, can be considered the embodiment of Badri’s spiritual and scientific revolution.

Conclusion

Throughout his life, Malik Badri sought solutions within the Islamic framework against the problems of our age (Badri, 1976, 1987; 1996; 1997; 1998) and succeeded in expressing and gaining acceptance in the international secular world. This effort of Badri is also a reflection of his professional and spiritual life. The scientific and spiritual legacy he left behind is the work of a life devoted to service. Badri, who is extremely devoted to spiritual practices in his private life, warned those around him to take spirituality into their therapy in the last periods of his life. He advised them to look at the example of the Prophet and ask themselves what he would have done. Thus, Badri, with his personality and studies, encouraged to search the sources of knowledge in the Islamic tradition for psychology and encouraged him to find life from spirituality (Rothman, Ahmed, Awaad, 2022).

In his lectures and speeches, he almost spoke to people’s hearts with his warm, wise attitude, but he also attached importance to being scientific. What he always wanted from his students was to pursue scientific knowledge, but not to give up critical thinking. He was particularly sensitive to theories in psychology that were contrary to his own religious and cultural values.

Badri, who started to work as a faculty member at Istanbul Sabahattin Zaim University in 2018, continued his duty in Istanbul until his illness worsened. With his death on February 8, 2021, the world lost not only one of the influential Muslim intellectuals of the 20th and 21st centuries, but also a scientific and spiritual revolutionary.

References

Ağılkaya Şahin, Z. (2018). Din ve psikoloji arasındaki uçurum gerçekten ne kadar derin? Psikoterapilerdeki dini izler. Cumhuriyet Theology Journal, 22(3): 1607-1632.

Ağılkaya Şahin, Z. (2019). Müslüman psikologlar kertenkele deliğinden çıktı mı? İslami Psikoloji alanındaki gelişmeler. Turkish Studies, 14(2): 15–47.

Ağılkaya Şahin, Z. (2020). Psikoloji ve psikoterapide din. İstanbul: Çamlıca.

Badri, M. (1963). The influence of cultural deprivation on the goodenough quotients of Sudanese children. Journal of Psychology.

Badri, M. (1964). The psychology of Arab children’s drawings. Al-Fath Publishers.

Badri, M. (1966). Recall of Proverbs as indicator of cultural orientations. The American University of Beirut Festival Book.

Badri, M. (1972). Customs, traditions and psychopathology. Sudan Medical Journal, 37(3).

Badri, M. (1973). Islam and Psychoanalysis. Emirate’s Yearbook.

Badri, M. (1982). The essentials of mental health for the Muslim child. Ri’ayat attufoolah fil Islam, 98-135.

Badri, M. (1987). Islamic social psychology in the aid of AIDS prevention. Ahfad University Journal.

Badri, M. (1996). Counselling and psychotherapy from an Islamic perspective. AlShajarah: Journal of ISTAC, 1(1&2).

Badri, M. (1996). The wisdom of Islam in prohibiting alcohol. IIIT.

Badri, M. (1997). The AIDS Crisis: An Islamic Sociocultural Perspective. ISTAC.

Badri, M. (1998). The AIDS Dilemma: A Progeny of Modernity. The Islamic Medical Association of South Africa.

Badri, M. (1998). The AIDS Dilemma: A Progeny of Modernity. The Islamic Medical Association of South Africa.

Badri, M. (2002). Islamic versus Western Medical Ethics: a moral conflict or a clash of religiously oriented Worldviews?” FIMA Yearbook.

Badri, M. (2008). The harmful aspects caused by the submissive approach of Muslim psychologists to Secular Western psychology (Arabic). AT-Tajdid, 12(23): 189-216.

Badri, M. (2009). The Islamization of Psychology. Its “why”, its “what”, its “how” and its “who”. N. Noor, (Ed.) Psychology from an Islamic Perspective: A Guide to Teaching and Learning içinde (pp. 13-42). Malaysia: IIUM.

Badri, M. (2012). Why Western psychotherapy cannot be of real help to Muslim patients? The Sudanese Journal of Psychiatry, 2(2): 3–6.

Badri, M. (2013). Abu Zayd al-Balkhi’s sustenance of the soul: The cognitive behavior therapy of a ninth century physician. International Institute of Islamic Thought.

Badri, M. (2018a). Contemplation – An Islamic Psychospiritual Study. The International Institute of Islamic Thought.

Badri, M. (2018b). International Association of Islamic Psychology Kongresi Açılış Konuşması, September, 26-28 2018, Istanbul.

Badri, M. (2021). El-Cevanib’ul-Atıfiyye Fi Hayatü’l-Enbiya: Keşf ve Taamulaat Nafsiyah. IIIT.

Badri. M. (1987). Islamic Social Psychology in the aid of AIDS prevention. Kuveyt II. AIDS Conference Paper. Ahfad University Journal.

Bedri, M. (2018). Müslüman Psikologların Çıkmazı (Trans. İ. Kaya). Istanbul: Mahya Publication.

Khan, R. (2021). Prof. Dr. Malik Badri’yle Psikolojiyi İslamileştirme Katkıları Üzerine Bir Görüşme (Trans. Ü. Balıkçı). İLSAM Akademi Dergisi, 1(1): 139-152.

Marsella, A. (2013). All psychologies are indigenous psychologies: Reflections on psychology. apa.org/international/pi/2013/12/reflections.aspx (12.12.2018).

Misra, G. (1996). Psychological science in cultural context. American Psychologist, 51: 496-503.

Moghaddam, F. (1987). Psychology in the three worlds: As reflected by the crisis in social psychology and the move towards indigenous third World psychology. American Psychologist, 42, 912-920.

Rothman, A., Ahmed, A., & Awaad, R. (2022). The Contributions and Impact of Malik Badri: Father of Modern Islamic Psychology. American Journal of Islam and Society, 39(1-2): 190–213.

Sloan, T. (1996). Psychological research methods in developing countries. S. Carr & J. Schumaker (Eds.) Psychology and the developing world içinde (pp. 38-45). Praeger.