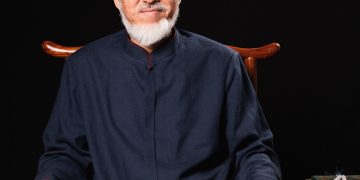

Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian. Incarcerated Childhood and the Politics of Unchilding. Cambridge, 2019.

“Unchilding” is a term we do not often encounter in the social sciences literature; however, it is a reality that we can clearly encounter in the policies of settler colonial states. The term refers to the use of children as political capital, stripping them of their childhood and rights to serve the political and military ambitions of these states. From the earliest settler movements in America to the colonization of Asia and Africa, settler-colonial states, some of which are still active today in various regions, continue to violate international children’s rights parallel to political violence. In these states, there is a vast mechanism of violence against the children of racially marginalized populations, including imprisonment, injury, forced disappearance, trauma, colonial violence, and armed occupation (Shalhoub-Kevorkian, 2019).

The term “unchilding” was first coined systematically and explicitly by Palestinian academic and human rights advocate Professor Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian. In her book Incarcerated Childhood and the Politics of Unchilding, she sheds light on the implementation of this term in Palestine while particularly focusing on Israel’s policies of unchilding towards Palestinian children. Thanks to the book, which includes historical records and direct testimonies from the Palestinian people, the term “unchilding” has gained a permanent place in the literature. As we delve into the six chapters of the book and its main themes, we will also integrate the testimonies of Palestinian children featured in the book.

In the first chapter, titled “Childhood as Political Capital,” the author discusses two different approaches of settler-colonialist Israel toward Palestinian children. The first approach claims to take a humanitarian perspective, asserting that a “compassionate intervention” (p. 1) is necessary for Palestinian children to adopt a modern and civilized lifestyle. It argues that it is best for these children to be detached from their families and local cultures and -through a blatantly racist and colonialist discourse that we are historically familiar with- that rescuing them from their uncivilized and backward cultures is essential. In this regard, the book points out how Israel has legitimized its policies of intervention in Palestinian children’s education and separation from their families under the guise of child protection services. The second approach is based on dehumanizing and demonizing Palestinian children. Thus, every crime committed against Palestinian children, such as killing, injuring, arresting, etc., is legitimized by stripping them of their childhood identity and portraying each one as a “potential terrorist” (p. 9).

Every crime committed against Palestinian children, such as killing, injuring, arresting, etc., is legitimized by stripping them of their childhood identity and portraying each one as a “potential terrorist.”

The second chapter, titled “Caging: From Lydda, 1948, to Hebron, 2018,” starts with the testimonies of elderly Palestinians and sheds light on the tragedies experienced by Palestinians who were children during the Nakba in 1948. The author then examines the incarceration of Palestinians through the term “caging.” Despite being in their own homes, Palestinians living under settler occupation are confined within physical, psychological, and even metaphysical cages because of the oppressive Zionist policies in the occupied territories. Hence, Palestinian children are condemned to be born and live in a cage filled with guards. Abu Manneh, who was a child during the Nakba, describes his thoughts as a child during that time: “They took everything from us; my food, my life, my movement, they control everything… and we have no protection… What can I do… What can we do?” (p. 38-39).

The chapter titled “‘Our Existence Is Upsetting Them’: Gendered Violence and Unchilding in the Naqab” recounts Israel’s policies towards the Bedouin communities in the Naqab desert through the testimonies of witnesses. The Zionist regime appropriates the rights of these tribes using similar discourses and methods to European imperialist narratives. The author also emphasizes how Israel utilizes sexual violence against women and girls and mandatory birth control as control mechanisms while appropriating these rights.

Titled “‘They Made My Parents into Prison Guards’: Childhood, Parenthood, and the Carceral Politics of Home Arrest,” the fourth chapter of the book begins with the striking words of a 15-year-old child from Jerusalem: “Just look at the attacks by settlers in Silwan or Ras al-Amud. You realize that they send them to attack us, and then we get arrested. How many times was I arrested and released, arrested and released? … They turned my house into a prison (he is under house arrest) and made my parents into prison guards… We all want freedom, but we can’t have it even inside the walls of our own homes” (p. 73). In this chapter, we witness Israel’s practices of house arrest in occupied East Jerusalem, where children are arrested and subjected to torture in prison. House arrest disrupts the dynamics within Palestinian households, stripping Palestinian children of their childhood rights and parents of their parental rights, forcing them into the role of guards for their children. Thus, the settler colonialist state of Israel uses house arrest as a tool of ethnic domination, making the institution of Palestinian family insecure and unstable.

The settler colonialist state of Israel uses house arrest as a tool of ethnic domination, making the institution of Palestinian family insecure and unstable.

The fifth chapter of the book, “Unbreakable: The Intimacy of Torture and the Children of Gaza,” begins with the depiction of how Israeli groups and politicians dehumanize Gazan children and their parents through genocidal rhetoric. As seen in settler colonial states established in different parts of the world throughout history, portraying the local population as “nonhuman others” (p. 103) allows these states to justify any oppression against the locals as a legitimate defense. In this sense, Shalhoub-Kevorkian explains how the Zionist project views Palestinian children as beings to be eliminated in order to maintain ethnic superiority in the region but also tries to establish a moral hegemony by portraying this as “collateral damage” in the fight against terrorism to the global media. Despite enduring political violence, occupation, oppression, and brutality throughout their childhood, we hear the voices of Palestinian children throwing stones against colonial power: “I want to become a journalist to tell my story and scandalize the Israelis. If I can’t be a journalist, I’m going to be a lawyer to defend my homeland. It’s our right to live in peace!” (p. 109).

The title of the sixth and final chapter is “Children as Political Capital: Unchilding and the Incomplete Death.” As described in the first chapter, the author defines the colonial regime’s perception of Palestinian children as either a threat or backward and in need of guidance as a “dispossession” policy while stripping them of their culture, families, environment, and childhood. The ideology of superiority, derived from racial violence and religious scriptures of Judaism and executed as state policy, is at the core of unchilding against Palestinian children. The settler-racist state, viewing itself as the rightful inhabitant of the land and Palestinian children as outsiders and disposable others, is not held accountable for violating children’s rights. Finally, the author concludes by portraying the resistance of Palestinian children against the Zionist regime. Despite questioning why no one stops the injustices against them and why their collective traumas are ignored and silenced, they directly confront Israel with their own resistance and resilience. Their resistance persists as one of the greatest threats to the settler colonial regime, aimed at claiming their childhood rights and their rights to live and die with dignity: “We are not afraid of them; despite everything they have done to us, we are not afraid of them… They killed my family, injured my people, demolished my house; that’s why I am stronger” (p. 133).

The settler-racist state, viewing itself as the rightful inhabitant of the land and Palestinian children as outsiders and disposable others, is not held accountable for violating children’s rights.

Before concluding, I would like to shed light on current events with the narratives from the book. The term “unchilding” has been in the spotlight since 2015, when 13-year-old Ahmad Manasra, who was arrested for a crime committed by his cousin, was sentenced to years-long solitary confinement despite having severe psychological health problems. Manasra is now 21 and still in custody (Amnesty International, 2023). This case demonstrates that the Zionist regime disregards any regulations concerning children and mentally ill individuals when it comes to the Palestinian people and Palestinian children at the international level. Recently, in the media, we often see Palestinians – especially those from Gaza – being referred to as “children of darkness,” or Hamas and ISIS being portrayed as similar entities, attempting to legitimize war crimes through Israeli state propaganda. Despite the blatant genocidal statements and actions of senior Israeli officials, politicians who repeatedly declare the phrase “Israel has the right to defend itself” indicate that Israel is not expected to pay any price, although even the right to life of Palestinian children is taken away because Palestinian children continue to be forcibly stripped of their childhoods and subjected to policies of “unchilding.”

References

Israel/OPT: After nearly 2 years in solitary confinement, Ahmad Manasra too ill to attend his hearing (2023). Amnesty International. Retrieved from https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/09/israel-opt-after-nearly-2-yearsin-solitary-confinement-ahmad-manasra-too-ill-toattend-his-hearing/

Shalhoub-Kevorkian, N. (2019). Incarcerated childhood and the politics of unchilding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.