This text has been translated from the original Turkish version.

Global media has finally begun to pay attention to Sudan; unfortunately, it appears that large-scale massacres had to be witnessed for this to occur. The massacre that took place in El Fasher, where more than two thousand innocent people were brutally killed in a single day, has become a turning point for Sudan. However, such massacres have been taking place in Sudan for a long time; incidents similar to those in El Fasher had already occurred in El Geneina and Al Jazirah. Sudan’s greatest misfortune is that the civil war and turmoil into which it has fallen coincided with the genocide perpetrated by Israel in Gaza.

Is there, then, any explanation for these massacres and the blood that has been shed? No, there is no reasonable explanation that can be offered. For the past 30 months in Sudan, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), that is, the army, and the entity known as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have been engaged in open armed conflict. Both actors are struggling to establish territorial control. In parallel with this struggle, a large-scale humanitarian crisis is unfolding. The first shot was fired in April 2023, and since then, Sudan has been the stage for the confrontation between these two forces, neither of which has been able to prevail over the other. At first glance, what appears is a power struggle over who will rule Sudan, alongside external actors that seek to benefit from this struggle.

As will be recalled, the rule of Omar al-Bashir in Sudan came to an end in April 2019. While street protests driven primarily by economic hardship played the leading role in the downfall of the regime, a bloodless coup was carried out jointly by the army and the RSF. The Transitional Sovereignty Council was rapidly established, bringing together both the coup leaders and the civilian groups that had organized the protest movements in the streets; however, disagreements between these actors began to manifest themselves from the very first day. Initially, tensions between the military and civilian components came to the fore. At this point, the removal of civilian representatives did not take long, and soon thereafter, disputes among the military elements themselves surfaced openly. It was at this juncture that the position of the RSF became decisive.

Where did the entity known as the RSF, which today hangs over Sudan like a nightmare, come from, and what does it seek? Answering this question may be useful for understanding what is happening in Sudan. When we look at Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, nicknamed “Hemedti,” who leads the RSF, we see that he emerged on the Sudanese scene in connection with the regional crisis that unfolded in Darfur in 2003. Hemedti, who began to operate in coordination with the Sudanese state’s active intelligence units in Darfur, rapidly turned, together with the men he recruited and the support he received from intelligence, into a force that suppressed several armed groups that had launched an insurrection against the state in Darfur. At the local level, this structure, referred to among the population as the “Janjaweed,” became the stuff of nightmares for the people of Darfur: using methods similar to those it employs today, it raided villages, looted, killed, and committed crimes against women. In other words, the RSF’s criminal record has been exceedingly extensive for more than the past twenty years.

The Janjaweed militias, which had become a valuable instrument for the state, were, before they could slip out of control, subjected to a strategic maneuver by the government. This structure was legalized and integrated into the state’s security apparatus. From this stage onward, the now-legalized militias began to appear on the Sudanese scene under the name Rapid Support Forces (RSF), and they turned into the regime’s guardian angels. The Bashir regime, of course, soon realized that it had created a Frankenstein’s monster with its own hands; however, for Hemedti, whose forces were growing in number, establishing external connections, and seizing control of gold fields in Darfur, the game was only just beginning.

By taking part in the process that led to the overthrow of Omar al-Bashir, the RSF rapidly became the most influential actor in the state after the army. Hemedti assumed the position of the second-ranking figure in the newly established Transitional Sovereignty Council; he undertook foreign trips, held rallies across the country, and frequently signaled that he was a candidate to govern the country. In the meantime, he was also appointing his own family members and trusted associates to strategic positions.

In 2021, Sudan entered a normalization process with the United States; however, in essence, this was primarily a normalization with Israel. The precondition set by the United States for removing Sudan from the list of state sponsors of terrorism, on which it had been placed for 20 years, was the signing of the Abraham Accords. During this process, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, who chaired the Sovereignty Council, and Hemedti, who served as the Council’s second-ranking member, held various meetings with Israeli officials. In this way, Israel, after a long hiatus, found the opportunity to re-enter the Sudanese arena.

At the beginning of 2022, under mounting pressure, Prime Minister Abdullah Hamdok, the most prominent figure of the civilian wing, announced his resignation and relinquished his post. When clashes erupted in the country a year and a half later, one of the most important topics being discussed in Sudan was the plan to integrate the RSF into the army and thereby dissolve it within the armed forces, an initiative that Hemedti found far from appealing. Having been marketing himself to external actors as a candidate to rule Sudan, Hemedti was well aware that integrating his forces into the army would result in a significant loss of power. The disagreement that emerged between the RSF and the army soon escalated into open armed conflict. Benefiting from the financial resources gained by selling abroad the gold extracted from the mining sites under its control, the RSF had little difficulty in acquiring state-of-the-art military weapons and equipment. The inflow of weapons into the country in exchange for gold brought Hemedti and the UAE into a close embrace. At the same time, Israel also assumed its place on the scene as the invisible third actor in this relationship.

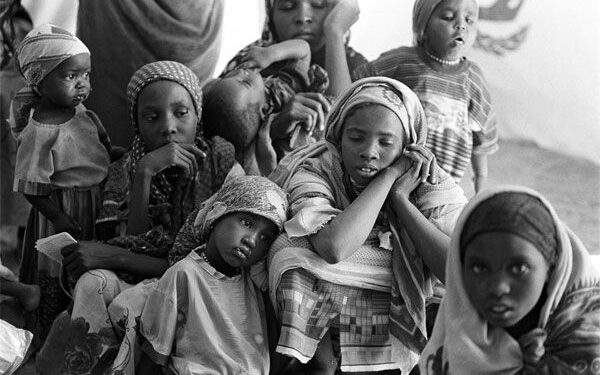

While the struggle for power in Sudan continues in the military realm, a major humanitarian crisis is also being acutely felt across the country. Economic, political, military, and humanitarian crises are intertwined. In a country with a population of 46 million, 14 million people have been displaced from their homes. According to United Nations data, 30 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance to varying degrees. As diseases such as cholera, malaria, and measles increase significantly, there is virtually no properly functioning healthcare system in the country. Ninety percent of school-age children in Sudan are deprived of schooling. This reality, in fact, demonstrates that the future of a significant territory within the Islamic world is at serious risk.

Another risk is that Sudan, which lost the South Sudan region in 2011, now stands on the verge of a new partition, since the structure known as the RSF holds significant territorial control in the Darfur and Kordofan regions. Looking at the country as a whole, roughly two-thirds of the territory is under army control, while one-third remains under RSF control. This situation, as in Libya, in effect means a de facto division of Sudan into east and west. This process implies the disintegration of Sudan, for a country that already experienced a partition in 2011 would find it extremely difficult to keep the remaining territory together if it were also to lose the Darfur region.

All eyes are currently turned toward the United States. At the request of Mohammed bin Salman, Donald Trump has announced to the public that he will take an interest in the Sudan file. However, the primary priority of U.S. foreign policy is to guarantee Israel’s security in these regions and to construct a surrounding environment made up of weak states; therefore, it would be exceedingly naïve to expect that any new process to be initiated with the United States will work to Sudan’s benefit. Sudan’s recovery can only be achieved through the activation of its own internal dynamics and the resolution of its chronic problems, such as the distribution and transfer of power.

Opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Platform: Current Muslim Affairs’ editorial policy.