This text has been translated from the original Turkish version.

Introduction

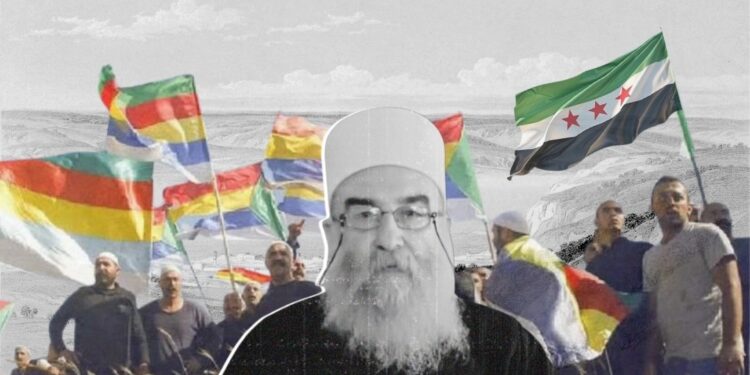

Among the Syrians celebrating in al-Karama Square in Sweida following the overthrow of the Bashar al-Assad regime by the opposition on December 8, 2024, were the Druze, one of the country’s most critical sectarian communities. The Druze, who had increased their protests against Bashar al-Assad starting in 2023 and loudly voiced their demands for his overthrow, spoke hopefully alongside other segments of society that the new administration would usher in a new era for the country. However, the fragility and unstable politics experienced during the process led to a confrontation between the Druze and the Damascus government. Divided into pro-regime and opposition factions within the Druze community after the 2011 civil war, the Druze began to coalesce around Sheikh al-Aql Hikmat al-Hijri and his opponent, Leith Balous, following the December revolution. Clashes with security forces in February, April, and, finally, July made visible a parting of ways for the Druze, centered on concerns about identity and existence. In the process, the claim of Israel’s “patronage” policy, using the Druze against the Syrian administration, played a role in the fragility of the Syrian Druze’s social and sectarian legitimacy.

The Process from “Jabal al-Arab” to “Jabal Bashan” and from “Muslim Druze” to “The Druze”

The concept of “Jabal Bashan” (Mount Bashan), first used in the message of Druze religious leader Hikmat al-Hijri, who reiterated his call for international intervention on October 11, essentially corresponds to Jabal al-Arab, which encompasses modern-day Sweida. The term “Mount Bashan” is a Hebrew concept meaning “flat ground.” Between 3000 BCE and 1200 BCE, it was known as the region east of Jordan, between Mount Hermon in Syria and the Ajloun Mountains in Northwest Jordan. Bashan, which appears in four different places in the Psalms, was attributed to the mountain found in that region, and the mountain was occasionally described as the Mountain of God and the Mountain of Camels, while at other times being named Mount Bashan. In the same context, Bashan, which also appears in the Bible, is described as “a place consisting of volcanic rock and soil, encompassing Hawran, the Golan Heights, and Lajat, with very fertile lands and abundant water, where wheat, barley, sesame, corn, lentils, and figs are cultivated.”[1]

The use of Bashan by Hikmat al-Hijri, inspired by the Torah and the Bible, rather than the official usage of Jabal al-Arab, is significant in the context of employing codes of political mentality. Indeed, name changes occasionally adopted in policies concerning minorities throughout the modern era still lead to conceptual confusion today. In this context, the Alawite community, another subject of debate in Syria, also began to be referred to as “Arab Alawites” starting from the period of the French Mandate. Due to this usage, which has continued since 1920, the definition of Alawites has been the subject of critical discussions not only in the Middle East but also concerning the categorization of all Alevis and Shiites worldwide. Jabal al-Arab, which the Hijri mentality seeks to rename as Jabal Bashan, is not essentially a very old term itself; the region received this name in 1946 after Syria gained its independence, and it became permanent with the emphasis of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1958. Jabal al-Arab, which Sultan Pasha al-Atrash particularly highlighted, was also accepted by all its inhabitants.[2]

The name Bashan, however, appeared before Hijri as the name of Israel’s occupation operation in Syria on December 10, 2024. The occupation, named “Operation Bashan Arrow,” was only one of the steps taken by the Israeli Ministry of Defense towards the Israelization of the region. The acceptance of Israel’s support by Hikmat al-Hijri during the July clashes and his demonstrated willingness to accept outside power against the Shara administration resulted from the desire to change the geopolitical code regarding Bashan. The Syrian Druze, in addition to preferring to remain loyal to the name Jabal al-Arab, are fiercely opposed to Hijri’s separatist rhetoric and reject the covering up of the current political crisis using a geographical term.

Another issue, perhaps more important than the geographical term in the Sweida crisis, is the omission of the adjective “Muslim” from the title “Sheikh al-Aql of the Muslim Druze” in Hikmat al-Hijri’s latest statement. The centuries-long debates regarding the sectarian identities and doctrinal foundations of the Druze have been shaped by the state they were affiliated with in the regions they inhabited following the withdrawal of the Ottoman Empire. In this framework, the Druze living under Israeli occupation have been stripped of their Muslim identity. At the same time, the Druze in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria have officially and unofficially continued to maintain their Muslim identity. The clearest protection of this identity is seen among the Syrian Druze. Indeed, the Sheikh al-Aql institution, which represents the Druze religious leadership, is recognized as the religious authority for the “Muslim Monotheistic Druze.” Hikmat al-Hijri’s choice to no longer regard the Druze as Muslim is emerging entirely as an Israeli project. As stated above, Israeli Druze are not defined as Muslim. The last two of the three clashes that took place in February, April, and July were essentially ignited over the question of the Druze’s Muslim identity. Despite all this, in the context of social and sectarian identity, the Druze continue to regard themselves as Muslim.[3]

The Syrian Druze’s Relationships with Their “Brothers”

The visit of the Lebanese Druze political leader, Walid Jumblatt, to Damascus on December 22, 2024, is directly linked to his anticipation of these very developments. Jumblatt’s awareness of Israel’s Druze policy and the close relationship between Hikmat al-Hijri and Muwafaq Tarif, the religious leader of the Israeli Druze, exposed the preemptive measure he sought to take. The anti-Israel stance of the Lebanese Druze was also an essential cornerstone in guiding Walid Jumblatt. Furthermore, the visit is significant because it underscores the efforts of both the political and religious wings in Lebanon to strengthen ties between the Druze communities of the two countries. These ties did not extend beyond cultural relations during the Bashar al-Assad era. Although serious questioning of the Shara administration began among the Lebanese Druze after the recent clashes in Sweida, Israel’s strategy to gain sympathy, particularly through Wiam Wahhab, another Druze leader and Walid Jumblatt’s opponent in Lebanon, has minimally affected the Druze community. Nevertheless, the close relationship between Leith Balous in Syria and Walid Jumblatt forms the cornerstone of efforts to prevent a rift between the brother communities of the two countries. Indeed, the first reaction to the crisis created by the name Jabal Bashan also came from Walid Jumblatt, who emphasized that the region would remain Jabal al-Arab.[4]

The Palestinian Druze under Israeli occupation, on the other hand, act in accordance with the instructions of Muwafaq Tarif. Whether or not the Syrian Druze hold the belief that they will be protected by Israel is not a measure, yet the new Syrian government is also seen as a threat by the Druze who are loyal to Israeli citizenship. Nevertheless, the sectarian relations between Israeli Druze and Syrian Druze, which include tomb visits organized by the religious leaders of the two countries, pave the way for Israel’s patronage policy.[5] These efforts to bring the two communities closer in this sense stand out as steps taken to separate the Syrian Druze from the Lebanese Druze.

The Druze Between Damascus and Hikmat al-Hijri

The escalation of a small-scale clash between Druze militias and Bedouins into a civil conflict in July created an enormous chasm between the Damascus administration and the Druze. Although the Druze largely wished to maintain their loyalty to Syria since the December revolution, the Sweida-centered protests continue. The protests’ purpose is being promoted as calls for autonomous administration, but reasons such as the region’s continuously deteriorating economic situation and the looming potential for a new conflict stand out more prominently. In the face of a potential conflict, the Damascus administration is choosing not to negotiate directly with Hikmat al-Hijri. Nevertheless, the Syrian government has undertaken several initiatives in the international arena to find a solution to the Druze crisis. In this context, on September 16, 2025, Syrian Foreign Minister Asaad Shaybani, in partnership with Syria, Jordan, and the U.S., announced plans to restore security in Sweida. Following his meeting in Damascus with Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi (who is of Druze denomination) and U.S. Special Representative for Syria Tom Barrack, Shaybani stated that a road map for a solution in Sweida “includes accountability for those who attack civilians, continuation of humanitarian and medical aid, compensation for those affected by the clashes, ensuring the return of displaced persons, restoration of basic services, deployment of local security forces, revealing the fate of missing persons, and the return of abductees,” signaling that a map for consensus had been drawn up.[6] Another striking development has been the reduction and subsequent silence regarding the messages in which Hikmat al-Hijri, whose authority had been strengthened since the December revolution, constantly thanked Israel for its presence. Indeed, Israel has shifted the focus of its Syria policy from Sweida to the Golan, and the Tel Aviv administration is currently continuing to advance in the Golan Heights. This situation indicates that Israel has, for the time being, backed away from its maneuver to protect the Hijri-supported Sweida. Leith Balous’s recent active engagement in a policy consistent with the government has brought into question Hijri’s political power.

Conclusion

The Druze issue in Syria continues within the framework of sectarian and social concerns. After Syria’s independence, the Druze staged various uprisings concerning the protection of legal and sectarian rights and the improvement of economic conditions. However, the 61-year Ba’ath era has played a leading role in pushing the Druze to withdraw into themselves and in weakening them both politically and militarily. In the post–8 December landscape, it is evident that the Druze continue to harbor the same concerns. The difference is that, parallel to the rise in Israeli aggression in the Middle East, more pronounced vulnerabilities are being experienced in Syria through Druze collaborators/allies. The persistent rhetoric of external support led by Hikmat al-Hijri and the shaping of the issue along sectarian lines during every moment of crisis appear to be the biggest problems facing the New Syria.

References

[1] https://urli.info/1ekvs

[2] http://sultanalatrash.awardspace.biz/geographicgblalarab.htm

[3] https://urli.info/1j7UV

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hvWz5sN2OQ0

[5] https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/syrian-druze-delegation-visits-israel-for-1st-time-in-52-years-reports/3510082

[6]https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/9/16/syria-jordan-us-unveil-plan-to-restore-security-in-suwayda-after-violence

Opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Platform: Agenda of the Muslim World editorial policy.