Abu-Lughod, L. (2015). Do Muslim women need saving? Harvard University Press

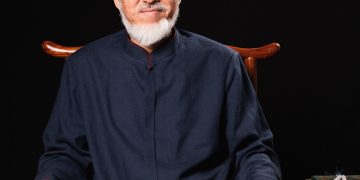

Lila Abu-Lughod, born 21 October 1952, is a Palestinian-American anthropologist. Having completed her MA and PhD at Harvard University, Abu-Lughod’s Egypt-based ethnographic work is central to her scholarly output. Her research focuses on cultural forms and power, the politics of knowledge and representation in Arab and Muslim geographies, gender dynamics in the Middle East, global feminist politics, and human and women’s rights-centred issues.[1] Penning important titles like Veiled Sentiments: Honor and and Poetry in a Bedouin Society published in 1986 and Do Muslim Women Need Saving? in 2013, she has been working intensively in this field for more than thirty years as a professor at Columbia University.

This book titled Do Muslim Woman Need Saving? is a collective presentation of the author’s thoughts and arguments based on her years of research and the experiences she carries. The author tries to answer the question posed in the book’s title from her own point of view and referring to her own experiences by touching on different points across different chapters. The work is a challenge and an intellectual antithesis to the framework created by the defenders of the dominant thought regarding “Muslim woman” and their presumptive mission to rescue her from the “plight”. The work can be considered as a manifesto since it contains the answer, “The phenomenon you call Muslim woman does not need to be saved by anyone”. In fact, the function of these conceptualizations and who they serve are the questions the book poses to the other side.

Despite her answer that Muslim women do not need to be saved, Abu-Lughod does not intend to cover up the plight of women, such as being killed, humiliated, persecuted and harassed. Even though she states that she has a sharp disagreement with the feminist organizations that try to put women into a single mould by ignoring their diversity and striving to “be like us”, she does not ignore the efforts of these organizations to seek justice and rights for the women of the world and does not see them as completely useless. The author invites these organizations to put aside their attempts to marginalise, denigrate, and even rescue women’s lives, which are shaped according to socio-political conditions, by calling them “their own culture” and to respect women’s different conceptions of rights, justice and future with the awareness that we live in an interactive world. According to the author, the idea that any injustice suffered by women is associated with their religion is an obstacle to a healthy understanding of these women. This derogatory language must be abandoned, and the stereotypical construction of Muslim women must stop.

Describing what she does as “writing against culture”, Abu-Lughod, as an anthropologist, takes a critical stance against the attitude of “stereotyping cultural differences”, which is an extension of anthropology’s connection with colonial powers. The author states that the bad situations women fall into or are subjected to are associated with Islam and a cultural phenomenon attributed to it with a reductionist approach; this approach constructs a geography that is characterized as “Islam Land”. One of the main theses of the book is to show that such a geography does not exist and that Islamic countries are not homogenous but different from each other. One of the main theses defended by the author with many arguments and under various headings is the idea that, contrary to the fact that women’s grievances are caused by Islam and a life associated with it, which is constantly instilled by the West; the reasons are rooted in the political functioning and struggles, economic order, oppressive regimes and gender inequality in the geographies where women live.

Another thesis defended is that this rescue call for women’s rights is an attempt to justify and legitimize many military interventions. The author even characterises these rescue military interventions as Crusades, emphasising the identical motive behind them. Another thesis defended in the book is that veil is not a dress that damages identity or restricts the freedom of Muslim women. The image of a covered woman that comes to mind when a Muslim geography is mentioned, and thus the role of the mentality that associates every negative thing in women’s lives with Islam hence any proposal to save women from this negativity will naturally aim at saving them from the veil as well. This idea of rescue, which places great emphasis on the concepts of consent, right to choose and freedom, insists on not accepting the idea that the veil is done with free will, as a part of women’s lives rather some women feel freer doing so. Visibly Muslim women do not endeavour to associate the negativities they face with their religion, nor do they try to adapt their clothing to the prevailing fashion.

“Rights and Lives”, the introductory chapter of the eight-chapter book, is the chapter in which the author includes sections on the lives of women from the Arab region. With the diversity she presents here, she wants to show that Muslim women cannot be presented in a single mould and a single type. From this point of view, she refutes the thesis that “Muslim women are under pressure because of their religion and culture”. The chapter titled “Do Muslim Women (Still) Need Saving?” mentions that military interventions made in line with political interests are tried to be legitimized under the guise of women’s rights. While the injustices suffered by women continue, these military interventions do not prevent these injustices and legitimacy is provided to political interests instead using the slogans of “saving women”. The second section titled “The New Common Sense” presents a criticism of the common sense as found in best-selling books that advocates going to war for women. Especially in the USA, books such as Half the Sky, The Honor Code and Caged Virgin, which focus on Muslim women’s rights, attempt to create a support for going to war for women. In these books, the causes of violations of women’s rights such as violence, rape and abuse are blamed on Islam. Criticizing these accusations, the author criticizes the West for not being self-critical and blaming Islam and Muslims, despite the fact that these crimes are committed at perhaps higher rates in the West.

The chapter “Authorizing Moral Crusades” questions the fact that books full of pornographic events, in which this common sense is legitimized through war for women, interestingly become popular titles. The fourth chapter, “Seductions of the Honor Crime”, deals with the issue of honor killings, a topic that is very common in these books. The fifth chapter, “The Social Life of Muslim Women’s Rights” in Palestine and Egypt, discusses the change and transformation of women’s pursuit of rights through political, and social factors and draws attention to the heterogeneous structure of the pursuit of rights across different geographies. As an anthropologist, the author in the last chapter titled “An Anthropologist in the Territory of Rights”, talks about her awareness of the objectification of women’s rights for political purposes after the intervention in Afghanistan and presents an evaluation of Islamic feminist women organizations. The concluding chapter titled “Registers of Humanity” consists of arguments in response to the question “Do Muslim women have rights or need to be saved?”. The chapter argues that the victimization of Muslim women should be analysed by taking into account various religious traditions, cultural forms, social and historical facts.

The author introduces her book as “an attempt to unravel how we should think about the question of Muslim women and their rights”. She emphasizes that the book does not promise a solution to these problems, but rather aims to make sense of the phenomenon and to broaden ways of thinking. In parallel with this claim, the book is supported by ethnographic studies and is careful to avoid stereotyping Muslim women in line with the very idea the author presents. The presentation of sections from the lives actually involved contributed to the sincerity of the flow and claims and contributed to the expansion of the perspective. The work makes a valuable contribution by showing that the world of thought, aspirations, meanings attributed to concepts and value judgements of Muslim women are not homogeneous. The point of criticism about this book, which is undeniably a qualified and respected work in many ways, is that it is written in a style that deepens the infrastructure of the East-West concepts and strengthens the otherness fiction. It is obvious that the policy of othering, in which the other side has been despised for centuries, is not solution-oriented. This criticism, which can be dropped as a small footnote to the work, is far from diminishing the importance of the issues that the work draws attention to and the value of bringing them to the fore. I believe that the work in question will be highly appreciated and admired by many women on the grounds that it translates their feelings and thoughts.

While there is an increase in the female populations of countries that are members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, a similar increase has not been recorded in the percentage of women employment in those countries. Yet, the fact that women participation in employment has stayed constant and has not declined could be considered a success.

* Marmara University, Faculty of Theology Graduate, History Department Student

[1] For information on Abu-Lughod see: https://anthropology.columbia.edu/content/lila-abu-lughod