BOOK REVIEW: Migration and Islamic Ethics: Issues of Residence, Naturalization and Citizenship

Migration and Islamic Ethics: Issues of Residence, Naturalization and Citizenship

Ray Jureidini & Said Fares Hassan (Eds.), 2019

The historical narrative of human migration has been a constant throughout civilizations. This phenomenon significantly influenced the inception of Islam, exemplified by the migration of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) from Mecca to Medina, a pivotal event that marked the commencement of the Islamic calendar. Emulating his journeys, followers of Islam have historically sought new homes in distant lands, driven by the quest for improved livelihoods and divine guidance. Having personally experienced migration twice, delving into this subject has not only been enlightening but has also provided a profound understanding of the historical, scientific, and religious aspects that underpin our existence. In the contemporary era, with the shadow of colonialism receding, Muslims constitute a significant portion of the global migrant and refugee population. In Migration and Islamic Ethics, the eleven contributors expand on the ethics of muʾākhā (brotherhood), ḍiyāfa (hospitality), ijāra (providing protection and support), amān (providing safety), jiwār (neighborliness), sutra (protection, esp. in case of marriage), and kafala (to guarantee someone) (p. 1) in general outlines and sociological case studies.

Ray Jureidini and Said Fares Hassan, the editors of the book, assert in the introduction that the book aims to present an analysis of Islamic ethics regarding migration without centering on a particular group. They believe that by exploring the principles and teachings of Islamic ethics, a deeper understanding can be gained regarding the issues surrounding migration. The book aims to provide a comprehensive perspective that transcends cultural, political, and geographical boundaries, fostering empathy and compassion for all individuals on the move in search of a better life. Through this inclusive approach, they hope to contribute to the ongoing dialogue on migration and ethics in a way that promotes unity, understanding, and respect among diverse communities.

The book aims to provide a comprehensive perspective that transcends cultural, political, and geographical boundaries, fostering empathy and compassion for all individuals on the move in search of a better life.

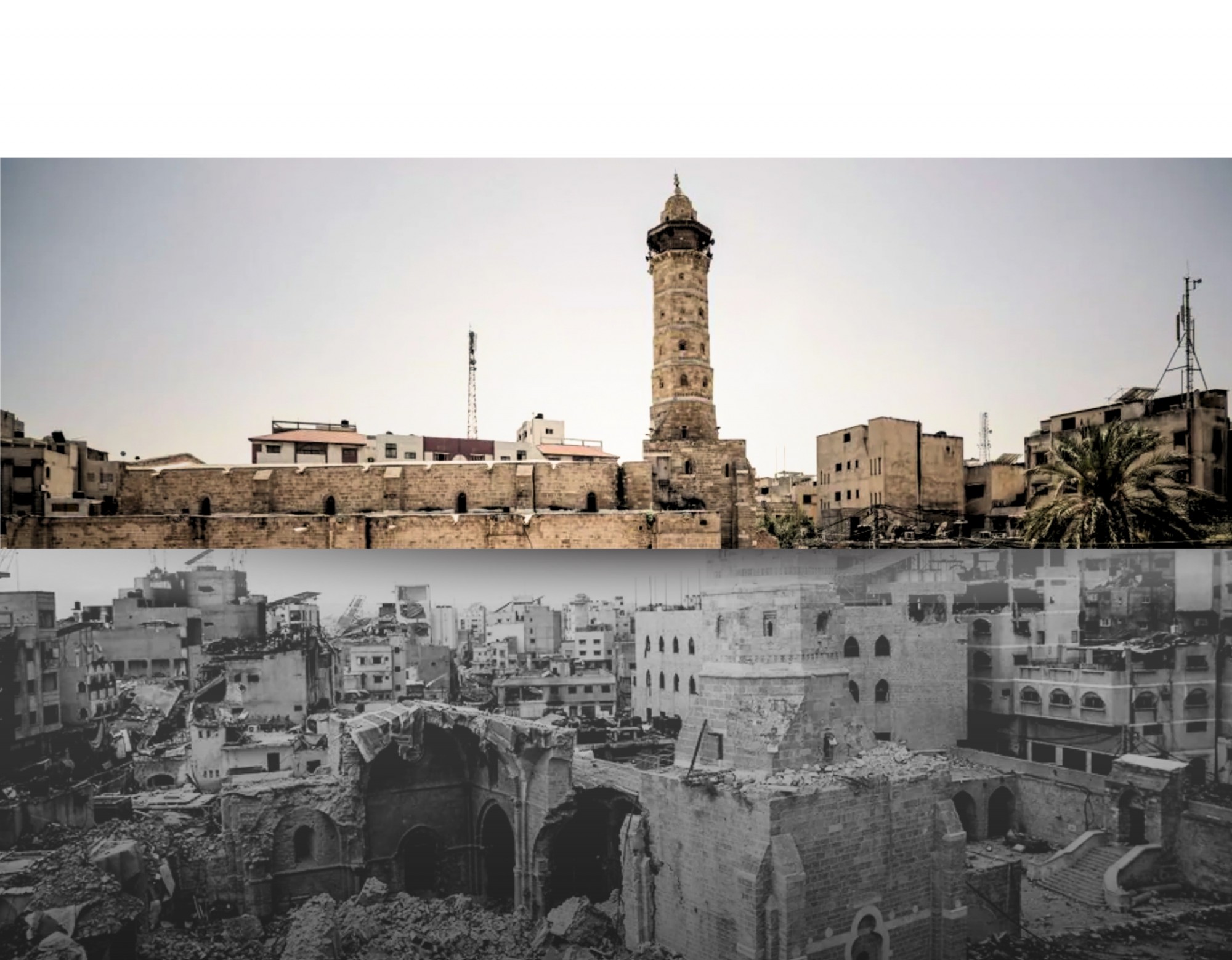

A distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Los Angeles School of Law, Khaled Abou El Fadl presents a compelling opening chapter entitled "Islamic Ethics, Human Rights, and Migration." In his meticulous analysis, he intricately depicts the contemporary Muslim world, shedding light on the political and environmental factors contributing to the widespread displacement of Muslims worldwide. Fadl not only attributes responsibility to the West for its role in the displacement within Muslim-majority regions but also underscores the accountability of the Arab world for its lack of intervention and hospitality towards these refugees. He critiques the notion of strictly adhering to the concept of "dar al-Islam," cautioning against the potential pitfalls of nationalism, ethnocentrism, and racism. His intention is not to deconstruct the concept but to highlight that, as Muslims, embracing the values of brotherhood and neighborliness can transcend the need for delineating borders. He says, “…it does take a certain amount of incredulous mythological thinking to continue ignoring the socio-historical realities, and insist that Muslims do in fact adhere to conceptual categories found in medieval texts written for a different time and place” (p. 23).

Succeeding Fadl’s eloquent introduction is Abbas Barzegar's chapter, which delves into the essence of Muslim humanitarianism. Termed "The Living Fiqh, or Practical Theology, of Muslim Humanitarianism,” this chapter centers on Islamic principles guiding Muslims in their altruistic endeavors. His insightful analysis sheds light on the intrinsic connection between Islamic values and humanitarian efforts, showcasing how acts of kindness and compassion are deeply rooted in the teachings of the faith. Barzegar approaches humanitarianism from a pragmatic perspective, emphasizing how preserving human dignity impacts intellect, life, faith, wealth, and posterity. These fundamental aspects collectively contribute to human development, which forms an ethical standard that should underpin much of human conduct. Barzegar advocates using Urf, or customary practices, as a framework for Muslims to infuse their humanistic values into daily life, adapting them to contemporary cultural and societal contexts.

In the fourth chapter, Tahir Zaman delves into the ethical considerations surrounding neighborly relations and the art of welcoming individuals into one's country. Türkiye and Syria serve as poignant examples, with Türkiye exemplifying a hospitable stance toward its neighbors seeking refuge and opportunities for peaceful coexistence. Zaman astutely highlights the inherent dichotomy within Turkish society in his subchapter "Dissonance—between Hospitality and Exclusion," where he underscores the governmental stance of facilitating the return of Syrians without encouraging their prolonged stay on Turkish soil in the spirit of neighborliness. Zaman continues to elucidate the Islamic principles underpinning the concept of Jiwar, emphasizing that it transcends the mere provision of temporary shelter, advocating instead for a harmonious daily cohabitation devoid of racial or linguistic biases. He mentions Arif, an Iraqi refugee he met in Damascus in 2010: “An Islamic narrative allows refugees to re-imagine their migration." Arif reminds us: “All the land belongs to God,” i.e., territorial sovereignty belongs to God rather than the state. Everyone has the right to move freely without hindrance—borders have no place under this schema. The Islamic narrative demands that the stranger is entitled to “find a place to live and work wherever [she goes]’” (p. 59-60).

Dina Taha writes a very poignant chapter about Sutra marriage, focusing on the case study of Syrian refugee single mothers in Egypt. Titled “‘Seeking a Widow with Orphaned Children’: Understanding Sutra Marriage Amongst Syrian Refugee Women in Egypt,” the chapter touches upon the disregard for women's safety in certain fatwas concerning their status as refugees and their vulnerability to exploitation for Sutra. This sociological analysis sheds light on culturally ingrained practices in the Eastern context within a postcolonial framework. It also illuminates that not all women affected by these circumstances perceive the Sutra solely as a form of protection; some exercise a degree of autonomy despite the challenges they face. To Dina Taha's astonishment, she finds herself reevaluating her perspectives on the nuclear family after witnessing these women's readiness to marry men for protection without love, a practice that challenges her preconceived notions influenced by colonial ideologies.

In “The Islamic Principle of Kafala as Applied to Migrant Workers: Traditional Continuity and Reform,” Ray Jureidini and Said Fares Hassan collaborate on this chapter to explain how kafala is a system often misunderstood and misapplied. Contrary to common misconceptions associating it with Western colonization, its essence lies in offering protection through granting a residence permit and sometimes taking care of their living expenses by providing them a job. “The main function of this regulation is to guarantee the interest of the work itself, the maintenance of security, the prevention of chaos and tension in the work environment. Once these regulations are set, both sides, employers and employees, should follow the contractual conditions and commit themselves to its conditions” (p. 97).

Despite numerous fatwas asserting that a contract-based kafala relationship lacks Islamic legitimacy, many migrants still unknowingly enter into agreements they struggle to comprehend, left isolated from their native language and cultural context. Even though these fatwas are subjective and culturally aware, there’s still a dearth of safeguarding the "makful" (sponsored/employees) from the "kafil" (sponsors/employers). Jureidini and Hassan conclude that the kafala system currently within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) is systematically different from that of the Islamic tradition, in which it becomes a commercial and exploitative transaction rather than a helpful act. It becomes up to the state to protect those exploited in their lands for their labor.

The following chapter, “Normativity of Migration Studies Ethics and Epistemic Community” by Dr. Sari Hanafi, presents a thorough sociological analysis of the Muslim diaspora in the West, examining it through intellectual, spiritual, and political lenses. This theme is further explored in chapters eight to eleven through different race groups in different regions. For instance, Radhika Kanchana’s chapter, “How do Muslim States Treat their ‘Outsiders’?: Is Islamic Practice of Naturalisation Synonymous with Jus Sanguinis?” is a sociological study concerning the citizenship laws in eighteen Muslim nations, challenging the misconception that acquiring citizenship under Islamic governance is unattainable. In many of these countries, being Muslim is not a prerequisite for citizenship. The discussion also encompasses the legal concept of jus sanguinis, which pertains to acquiring nationality through the nationality of one or both parents.

Rebecca Ruth Gould focuses her chapter on the historical narrative of the Caucasus region and the migratory trends of the nineteenth century. Throughout the historical recollection in “The Obligation to Migrate and the Impulse to Narrate: Soviet Narratives of Forced Migration in the Nineteenth Century Caucasus,” Gould explains the concept of freedom within the Chechen culture, alongside the different meanings of hijra for the people of Caucasus as they were forced to flee from the violent collision of the Ottoman and Russian empires. Seen as a means of Jihad and banishment, Gould argues that Hijra is a “paradoxically a unifying concept, a way of living with and through trauma, that gives meaning and structure to the experience of exile and displacement, including, for Chechens, the ongoing experience of the 1944 deportation” (p. 171).

Mettursun Beydulla records the mass Uyghur forced migration to Turkey and the US after the secular communist rule in China. Titled “Experiences of Uyghur Migration to Turkey and the United States: Issues of Religion, Law, Society, Residence, and Citizenship,” Beydulla highlights the dichotomy between migrating to a Muslim and a non-Muslim state and the process of integrating into different cultures and being subject to different laws during the migration period, simultaneously assimilating and becoming a legal or illegal citizen. He also touches upon the group’s tight grip on personal identity amidst their diaspora in the West, especially when affected by a complex assimilation experience.

In the eleventh and final chapter, Abdul Jaleel P.K.M. writes his research on a more optimistic perspective regarding the Arab migrants who found a new home under Hindu rule in Malabar through means of trade and economics in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. “Arab Immigrants under Hindu Kings in Malabar: Ethical Pluralities of ‘Naturalisation’ in Islam” seeks to challenge the negative portrayal of relocating to a non-Muslim territory based on medieval religious ideologies. Instead, Abdul Jaleel explores historical accounts that highlight positive instances of Muslims assimilating in distant non-Muslim regions under different political regimes, shedding light on the often overlooked but significant legal viewpoints regarding the integration of Muslims. This initiative also aims to counteract any anti-immigrant sentiments that complicate the naturalization process while highlighting the distinct contrast in the assimilation of Western and Eastern states.

Farida Elsaedy

Farida Elsaedy (Feride Elsaidi) is an English literature master's student and English teacher at Istanbul Bilgi University. Her work explores novels, films, and the intersections of art and storytelling. Originally from Egypt, she lives in Istanbul a...

Farida Elsaedy

Farida Elsaedy