Environmental Ethics: An Eco-Postcolonial Ethic Versus Ecological Apocalypse

In the current environment of Theravada Buddhism raging in Myanmar, Zionism ideology ruling the world elite, or the Hindutva movement rampaging in the self-proclaimed secular State of India, it might be argued that perhaps the recovery of pre-modern traditions of religion can be seen as more aligned with peace; and that secularism, despite its commitment to religious peace, can actually lead to a lot of religious violence.

This claim needs to be further investigated amidst the fad of several offshoots of environmentalism that we hear around ourselves. We have quite internalized (and quite rightly so) terms like eco-friendly, environmental-friendly, renewable resources/energy, deep ecology, ecosystems, biodiversity, green ecology, sustainable water management plans, environmental determinism, possibilism, and the list goes on. However, we may be checked in our environmental trajectory when we juxtapose these terms with locutions like green postcolonialism, postcolonial green, green criminology, environmental politics, greenwashing of Palestinian Naqba, Operation Green Hunt, and the like.

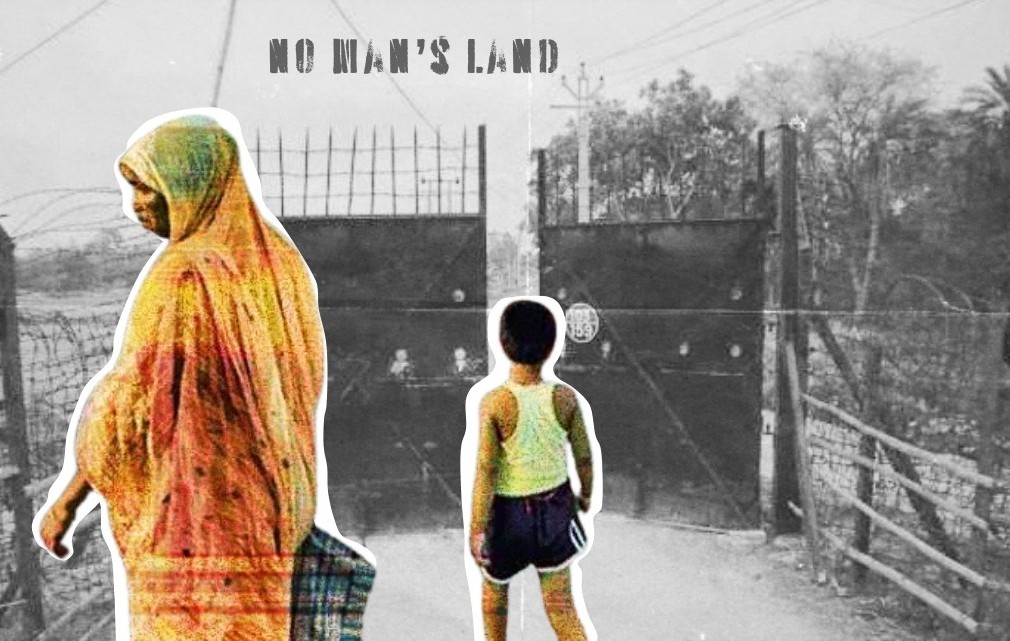

Though much greenwashing has gone down in history, we may like to consider three contemporary realms to see how environmentalism is playing out in their milieux. We may like to ask whether it is really environmentalism or only a shibboleth; environmentalism or environmental ethnocide; and eco-postcolonial ethic or an environmental incantation. Another possible question that we may like to ask is that is it purely incidental that the atrocities committed against the local people, their life, property, their habitat, and livestock, are the people who belong to the Muslim community.

To understand what exactly the difference between environmentalism and environmental ethic is, as I contend, we need to understand the basic difference between the two terms. Simply put, environmentalism is a concern “aimed at protecting the environment”. However, its extended meaning is a “theory that environment, as opposed to heredity, has the primary influence on the development of a person or group”. It is this second understanding that ropes in a wider concern about how the environment shapes human development and when we see genocidal waves ravaging the three realms of Rakhine, Palestine, India, or Indian-held Kashmir, we are compelled to revisit the usual understandings of the term of environmentalism. In all three cases, it is hardly a genuine environmental concern when we see the chaining and sawing of trees or the burning and demolishing of habitats of the local people, to give only one or two examples. We, therefore, need to look into an understanding of environmentalism that should be holistic enough to cater to all people and natural habitats in this world, indiscriminately.

Israeli troops intervene with farmers working in the West Bank.

Source: Middle East Eye

For an all-inclusive understanding of what goes around us, I suggest the term environmental ethics. Simply put it is an ethical statement of facts about a space invoking a historically informed environmentalism that would aim for a balanced and sustainable future of all sorts of existence on our earth (Aamir, 2023). In other words, in the context of these three post-colonies of Palestine, Indian-held Kashmir, and the case of Rohingya in the state of Rakhine, Myanmar, we may see pervasive blanket assertions of environmentalism. This brand of environmentalism seeks to foreground the purity of race, the rootedness of place, a nationalism that borders on a sort of cult of parochial nationalism, and has the propensity of transcending or sublimating history. In this age of sophisticated knowledge assimilation and knowledge production, it is time for informed environmentalism, or environmental ethics (as I suggest) that does not gloss over the aspects of hybridity, displacement, cosmopolitanism, or history. Since these three realms are post-colonies, we may also call it a postcolonial environmental ethic, a concern that looks into all three dimensions of postcoloniality, environmentalism, and ethic. It may alternately be termed eco-postcolonial justice, which also states the indigenous rights or environmental justice of a postcolonial place. The blatant disregard of these aspects occasions green criminology which, in fact, has a “harm-based approach.” This green criminology allows many “legal” activities that can be more destructive to the environment of human and non-human animals than those deemed illegal, as Damien Short would remind us.

The day-in and day-out carte blanche that Theravada Buddhism exercises in perpetrating the genocide of Rohingya people in the southwestern state of Rakhine in Myanmar, or the Zionist ideology of changing the landscape of an Arab place of Palestine, or carving out of demography to suit Hindutva ideology are examples of those harm based approaches that are occasioning green criminology on the part of the perpetrators. However, by passively accepting the status quo, the world seems to be complicit in this perpetration. As Robbins would like to put it and I contend that in the case of the three realms or any similar case around the world, environmental ethics evokes a moral philosophy that is needed to bring humanity out of its quiescent mode of becoming beneficiaries.

When we see ongoing persecution of the ethnic minority of Rohingya Muslims starting back from the 1960s; the forced evictions in the environs of Jerusalem, the continued harassment, intimidation, terrorization, and maltreatment of the Palestinians in and out of Israel since 1948, and even before it; oppression, subjugation, torture, cruelty, and killing in the Indian-held Kashmir and even other Muslims in the other parts of the Indian State; with the added factor (in the latter two realms) of interpellating the world consciousness into believing that the victims are perpetrators; we are compelled to understand the ethics of resistance of these people for their lives, lands, and properties. We are duty-bound to question the status quo for these or similar realms around the world. And this calls for an environmental ethic that takes into consideration environmental justice, social justice, and economic justice as parts of the same whole, not as dissonant competitors.

It is not that we do not have such models that have not gone down in history. We have had the Muslim Governance Model, in spite of all its weaknesses, inner fissures, and voracious games; and the contemporary European Union or the United States of American Model (though they have their limitations too), where human beings are existing quite peacefully even with all their differences in their belief systems (albeit with an intrinsic understanding that the ruling government laws will be dominantly applicable).

Though this may be a topic of another article, there is merit in considering an option of environmental ethics because it may evoke that lost ecumenism that the world was enjoying and exercising prior to this modern and postmodern world. It may be useful to consider (even hypothetically) the model of environmental ethics that has been given by Islam. Without going into much detail, suffice would be to see here that when Muhammad (صلى الله عليه وسلم) was given prophethood, he went to the people of the book for guidance. Warqa bin Nofel was a monk who vouchsafed his prophethood with the knowledge he had, as Allah states in the Holy Quran too: “Those to whom We gave the Scripture recognize him “to be a true prophet” as they recognize their own sons” (6: 20). It will also be environmentally ethical if we appreciate the fact that there are many laws in Islam that have been maintained from the earlier scriptures of the Old and the New Testaments. Therefore, the presence of a big Jewish diaspora living peacefully in various parts of the Muslim world (Avi Shlaim’s The forgotten history of Arab Jews may stand as only one example) versus the persecution of European Jews in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries may be cited as one example. Considering this ecumenical environmental ethic can, therefore, serve as a good way to separate the grain of environmental ethics from the chafe of blinkered logic of environmentalism.

It is an interventionist field of study, which can be a relevant lens to read the concerns of (postcolonial) spaces mired by incongruencies, and that interrupts the continued vilifications, rejections, and exclusions of ethical concerns in the blanket assertions of environmentalism. The word ethics further educes a transatlantic or prospective cosmopolitanism making an interstitial space for social, economic, and environmental justice, or “ethic of resistance” in the debates of environmental ethics/ eco-postcolonial ethic. This environmental ethics (EE) needs to be implemented in the proper sense of the word, lest we may have to face an ecological apocalypse in the world that we live in, because as Martin Luther would say: “The arc of the moral universe is big, but it bends toward justice.”

Rabia Aamir

Dr., Faculty of Arts & Humanities, National University of Modern Languages...

Rabia Aamir

Rabia Aamir