Islamophobia in the Balkan Media: Contemporary Perceptions in the Shadow of the Past

The Balkans play an important role as a major route for migrants on their journey to Europe. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) statistics, as of the end of April 2024, there were approximately 2500 refugees in the Western Balkans (44% in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 32% in Serbia, 8% in Kosovo, and 7% in Albania and Montenegro), while this number reached up to 8,000 in 2023. These changes in the number of migrants over different periods indicate that this region is a dynamic and variable migration route (UNHCR, 2024). During the major refugee crisis in Europe between September 2015 and March 2016, approximately 700,000 refugees used this route through Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, and Slovenia to reach their desired destinations (primarily Austria, Germany and Sweden) (Šelo Šabić & Borić, 2016). These statistics undoubtedly show that the Balkans, as a transit route, are highly vulnerable to large waves of migration and major crises that occur on the other side of the world. The fact that these refugees predominantly come from Muslim countries requires a broader consideration within a much more general social and cultural context, especially in relation to topics such as Islamophobia.

Individual Freedom in the Age of Algorithms

With the development of media technology and the widespread use of new technologies, individuals have strengthened their personal positions, at least against mass narratives. News is no longer a one-way stream; instead, it comes from a network of selected sources that were once monopolized by a few news centers, now integrated into the interests of each phone user. Naturally, this began to seem like a gateway to freedom. In the "world of algorithms," a follower could find their freedom not only in choosing sources but also in the possibility of becoming a source themselves. However, even when individuals joined the media network by creating a new account, they couldn't suddenly appear like a tabula rasa. They entered through this point with existing knowledge, contributing to society with materials they had acquired from it. Through this never-ending cycle of socialization, society imposed its codes even in the "personalized world of algorithms." Thus, people found themselves having to accept that, even in situations where they felt most free and subjective, their world of ideas and perceptions remained fragile and dependent on a specific social context.

Reactions justified by the promise of protecting society from perceived "threats" posed by refugees are used as a rationale for dehumanizing activities and violence through media portrayals. In this way, society is directly influenced by media depictions to feel that a social crisis is underway.

Media and the Perception of Migrants

The media is one of the most influential actors in shaping people's perceptions of the world and reality. The media uses frames to focus on certain aspects of reality while concealing others, leading audiences/readers/followers/listeners to react collectively and compelling them to align themselves with specific viewpoints (Entman, 1993). Bernard Cohen (1963), referring to this power of the media, argues that even when the media does not explicitly tell people what to think, it successfully guides them on what they should be thinking about, setting the agenda that occupies their minds. Media portrayal undoubtedly has a significant impact on public attitudes toward refugees as well. On the one hand, it can provoke hostility towards refugees, on the other hand, it can play an essential role in providing remedial support.

Existing studies show a strong link between media portrayals and the level of tolerance towards groups perceived as "others," especially immigrants and refugees (Kamenova, 2014). Some studies suggest that in societies where uncertainty prevails, the media's tendency to focus on negative rather than positive news stories can lead to extreme negative reactions towards immigrants and refugees, including dehumanization. Reactions justified by the promise of protecting society from perceived "threats" posed by refugees are used as a rationale for dehumanizing activities and violence through media portrayals. In this way, society is directly influenced by media depictions to feel that a social crisis is underway (Esses, Medianu & Lawson, 2013).

Refugees in the Political Labyrinth

"Uncertainty" has become a significant social reality in the Balkans. Historically, when the Balkans are mentioned, the region that comes to mind typically includes the eastern edge of Türkiye, Bulgaria, and Romania, along with Greece to the south. However, in recent times, some of the former Yugoslav countries (Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro, Kosovo) and Albania have increasingly been referred to under the term "Western Balkans," particularly highlighted within the EU integration process led by Germany. Although uncertainty in this region can be specifically evaluated in historical, political, and socio-economic contexts for each country, Bosnia and Herzegovina serves as a notable example, being periodically targeted by criticisms in refugee discussions due to the policies and rhetoric of neighboring countries. In 2019, during an official visit to Israel, then-President of Croatia, Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović, stated that the refugee crisis in her country was different from that in other European countries due to the Bosnia and Herzegovina factor. According to Grabar-Kitarović, the primary cause of instability in Bosnia and Herzegovina, right next to Croatia, was "radical Islamists being in power," their "connections with terrorist organizations," and their role in radicalizing the region through refugees (Kolinda on BiH: "Vrlo nestabilna, preuzeli je ljudi povezani s teroristima, pod kontrolom je militantnog islama". 2019).

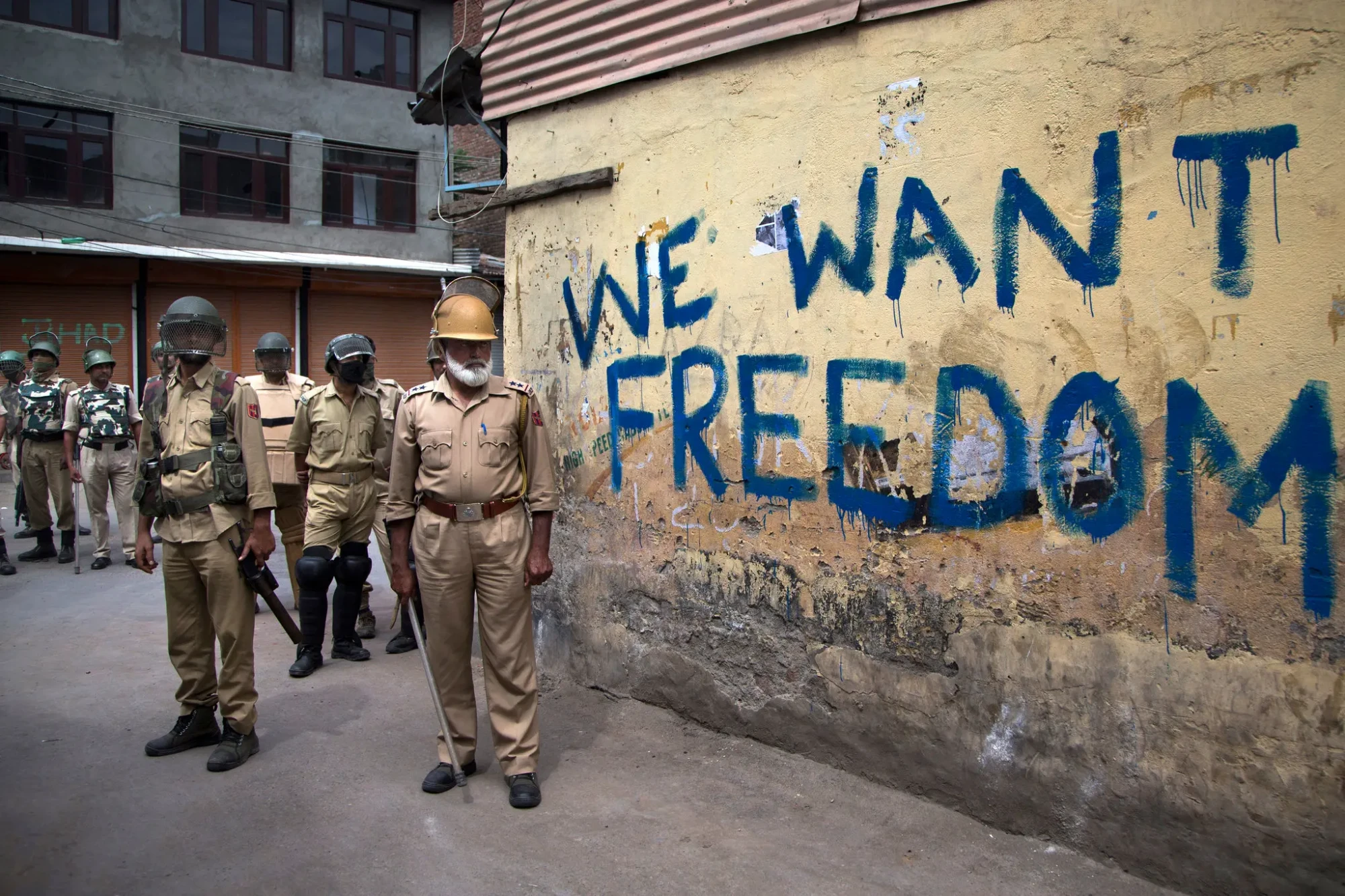

In another statement, Grabar-Kitarović claimed that around 10,000 radical Muslims were living in Bosnia and Herzegovina, serving as yet another example of the "refugee-Bosniak-terrorist" associations made by Croatia's top officials. Even though these allegations were strongly rejected and refuted by Bosniak politicians, similar accusations continued to be made by Croatian authorities. The fact that Grabar-Kitarović expressed such claims in Israel—one of the most globally controversial countries regarding its policies and actions against Muslims—can undoubtedly be seen as an attempt by Croatia to align itself with Israel under a common rhetoric, suggesting that both countries face similar issues, particularly given Israel’s tendency to label Palestinian Muslims as terrorists and portray them as security threats. Croatia’s treatment of refugees and the police interventions at its borders have also been widely debated by numerous national civil organizations and international agencies due to the severity of the human rights violations ("Sve snimke brutalnosti policije prema migrantima", 2021).

Croatian President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović and Israeli President Reuven Rivlin (Abir Sultan/EPA-EFE)

Former Bosnian Presidency Member and current President of Republika Srpska, Milorad Dodik, has frequently raised concerns about refugees in the context of their religious identities and security threats. Dodik accused Bosniak parties of attempting to alter the national and religious structure of Bosnia and Herzegovina by bringing in 150,000 migrants. He also stated that these migrants "threaten the current way of life" in areas where Serbs live, and therefore, they would not be allowed to settle there. Dodik openly declared that these migrants would be relocated by the police to the Federation entity, where Bosniaks are the majority ("Dodik optužuje bošnjačke stranke da planiraju 150.000 migranata smjestiti u BiH", 2018). Proposals to deploy the Bosnian Armed Forces to the borders have been consistently and vehemently rejected by Dodik and Serbian politicians. Consequently, while Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina's western neighbor, strictly controls its borders, refugees from Serbia can enter much more easily through Republika Srpska and are settled within the Una-Sana and Sarajevo Cantons, where Bosniaks predominantly live. The attitudes of both Serbian and Croatian politicians in Bosnia and Herzegovina are reflected in the media, where refugees are portrayed as violent threats to security and culture.

These outlets, known for their racist rhetoric against Bosniaks and Albanians, often redirect this hatred towards refugees, thus continuing their prejudice against Muslims by merely "changing the packaging

The Changing Face of Islamophobia

The intertwining of refugee news with social, historical, and cultural connotations in Balkan media is most evident in the case of Serbia. The "Migrant Crisis Report: Between Manipulation and Publishing Ethics" published by the Independent Journalists' Association of Vojvodina provides many examples of how hatred and negative biases against Muslims are incited through refugee coverage in Serbian media (NDNV, 2021). Although media close to the government follows similar rhetoric, the most significant platforms for these types of news are social media pages and groups, which reach hundreds of thousands of followers and criticize the government for allegedly turning a blind eye to the "Islamization of society." These outlets, known for their racist rhetoric against Bosniaks and Albanians, often redirect this hatred towards refugees, thus continuing their prejudice against Muslims by merely "changing the packaging" (“Medijska slika ljudi u migracijama u Srbiji: Ksenofobija, mizoginija i islamofobija”, 2021). Examining such reports, it becomes clear that misleading news in the Serbian media includes false reports on the number of migrants, the meaning of the term "refugee," and the number of incidents and cases, as well as manipulations related to the alleged Islamization of society (NDNV, p. 13). These reports not only create a negative image of migrants but also pave the way for violent "activities" against refugees organized by various nationalist groups under the guise of "park cleaning" events ("Narodne patrole" zovu na "čišćenje" parka kod Ekonomskog; NVO: "Čistite deponije", 2020).

Threat or Just a Human?

In European media, coverage of migrants often oscillates between focusing on citizens' security or human rights, reflecting the dichotomy between securitization and humanitarianism (Siapera et al., 2018). On one side, some argue that migrants pose security threats, while others advocate for migrants' human rights, emphasizing the need to provide them with aid and shelter just like any other citizens. Research shows that media narratives on refugees can vary significantly depending on the government's stance in a given country. For instance, a study on refugee discourse in Croatian media (Čepo et al., 2020) found that while most articles remained neutral according to journalistic standards, the shift in government ideology—from social democrats focusing on humanitarian aspects to security-focused conservatives—coincided with an increase in negatively framed reports on migrants. This negative portrayal grew alongside the rising number of refugees and migrants attempting to cross the Croatian border and the national authorities' efforts to protect EU borders. The new, more nationalist government strongly emphasized its obligation to protect the Schengen area, increasingly adopting a security-driven narrative. This pattern reflects broader trends across Europe, where media outlets may align with the ideological leanings of the government in power, influencing public perception of migrants either as threats or as individuals deserving of protection.

Clean Parks

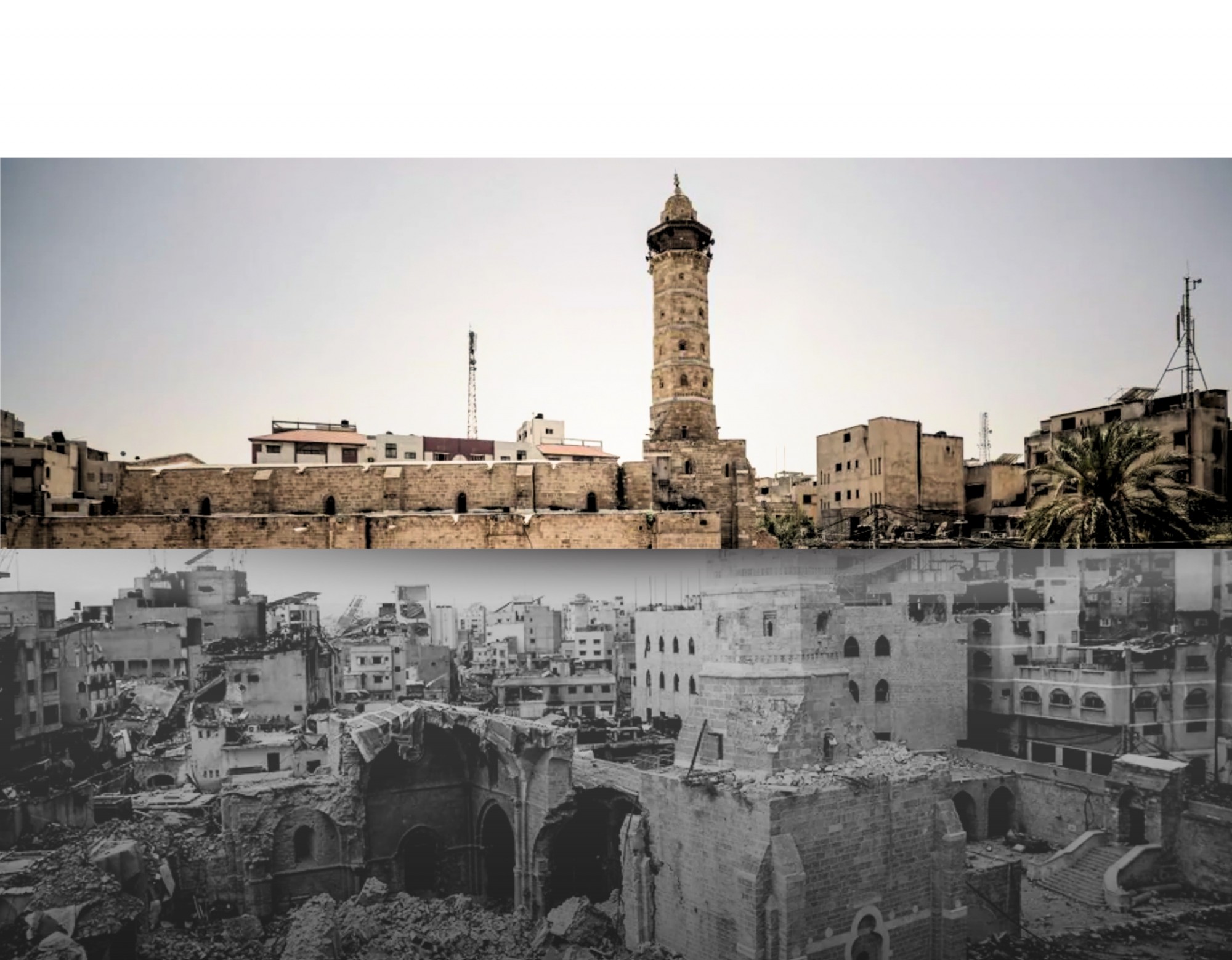

In conclusion, the refugee issue has the potential to become a central topic in political debates across the Balkans. Media plays a crucial role in shaping public perception, not by informing individuals about what to think, but by using its agenda-setting power to highlight the perceived extent of the "threat." Given the deep historical, cultural, political, and socio-economic resonances of the refugee issue in the Balkans, it cannot be confined solely to a security-humanitarian dichotomy. With the widespread use of social media, the control over news narratives has long been removed from journalists. Instead, individuals have become centers for producing and seeking out news that reinforces their existing worldview, often disregarding professional journalistic norms and ethics. In this sense, the Islamic religion and the Ottoman legacy, both of which hold significant historical and cultural importance in the Balkans, have become scapegoats in the face of rising racism and chauvinistic nationalism. Afghan, Syrian, or Pakistani migrants passing through the Balkans are often associated with the Ottoman Empire, which itself is being revived from the past and discussed in the context of contemporary terror threats. In this blurred landscape, misleading news reports overshadow the humanitarian aspect of the debate, dehumanizing people and, as exemplified above, framing calls to remove refugees from shared living spaces as efforts to "clean the parks."

References

Čepo, D., Čehulić, M., Zrinščak, S. (2020). What a difference does time make? Framing media discourse on refugees and migrants in Croatia in two periods. Hrvatska i komparativna javna uprava: Cčasopis za teoriju i praksu javne uprave, 20(3), 469-496.

Cohen, B. C. (1963). The press and foreign policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dodik optužuje bošnjačke stranke da planiraju 150.000 migranata smjestiti u BiH. (2018, July 13). Večernji.hr. Retrieved from: https://www.vecernji.hr/vijesti/dodik-optuzuje-bosnjacke-stranke-da-planiraju-150-000-migranata-smjestiti-u-bih-1254053

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51-58.

Esses, V. M., Medianu, S., & Lawson, A. S. (2013). Uncertainty, threat, and the role of the media in promoting the dehumanization of immigrants and refugees. Journal of Social Issues, 69(3), 518-536.

Kamenova, D. (2014). Media and othering: How media discourse on migrants reflects and affects society’s tolerance. Politické vedy, 17(2), 170-174.

Kolinda o BiH: "Vrlo nestabilna, preuzeli je ljudi povezani s teroristima, pod kontrolom je militantnog islama". (2019, July 30). Faktor.ba. Retrieved from: https://faktor.ba/bosna-i-hercegovina/aktuelno/kolinda-o-bih-vrlo-nestabilna-preuzeli-je-ljudi-povezani-s-teroristima-pod-kontrolom-je-militantnog-islama/20210

Medijska slika ljudi u migracijama u Srbiji: Ksenofobija, mizoginija i islamofobija. (2021, March 1). Al Jazeera Balkans. Retrieved from: https://balkans.aljazeera.net/teme/2021/3/1/medijska-slika-ljudi-u-migracijama-u-srbiji-ksenofobija-mizoginija-i-islamofobija

"Narodne patrole" zovu na "čišćenje" parka kod Ekonomskog; NVO: "Čistite deponije". (2020, October 21). b92.net. Retrieved from: https://www.b92.net/o/info/vesti/index?nav_id=1751166

NDNV. (2021). Izveštavanje o migrantima – Između manipulacije i etike. Nezavisno društvo novinara Vojvodine.

Šelo Šabić, S., & Borić, S. (2016). At the gate of Europe: A report on refugees on the Western Balkan route. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Siapera, E., Boudourides, M., Lenis S., Suiter J. (2018). Refugees and network Publics on Twitter: Networked framing, affect, and capture. Social Media + Society, 4 (1).

Sve snimke brutalnosti policije prema migrantima. (2021, October 6). Net.hr. Retrieved from: https://net.hr/danas/vijesti/sve-snimke-brutalnosti-policije-prema-migrantima-d557e476-2807-11ec-aaac-8a7b9af4653b

UNHCR. (2024). South Eastern Europe - Asylum Statistics April 2024.

Mustafa Krupalija

Mustafa Krupalija was born on March 13, 1990 in Sarajevo. After graduating from Uludağ University Faculty of Theology, he completed his master's degree in the Sociology of religion at Marmara University and then his doctorate in the same field at Ist...

Mustafa Krupalija

Mustafa Krupalija