Kitchen in the Migrant’s Suitcase: Migration, Food and Sociology

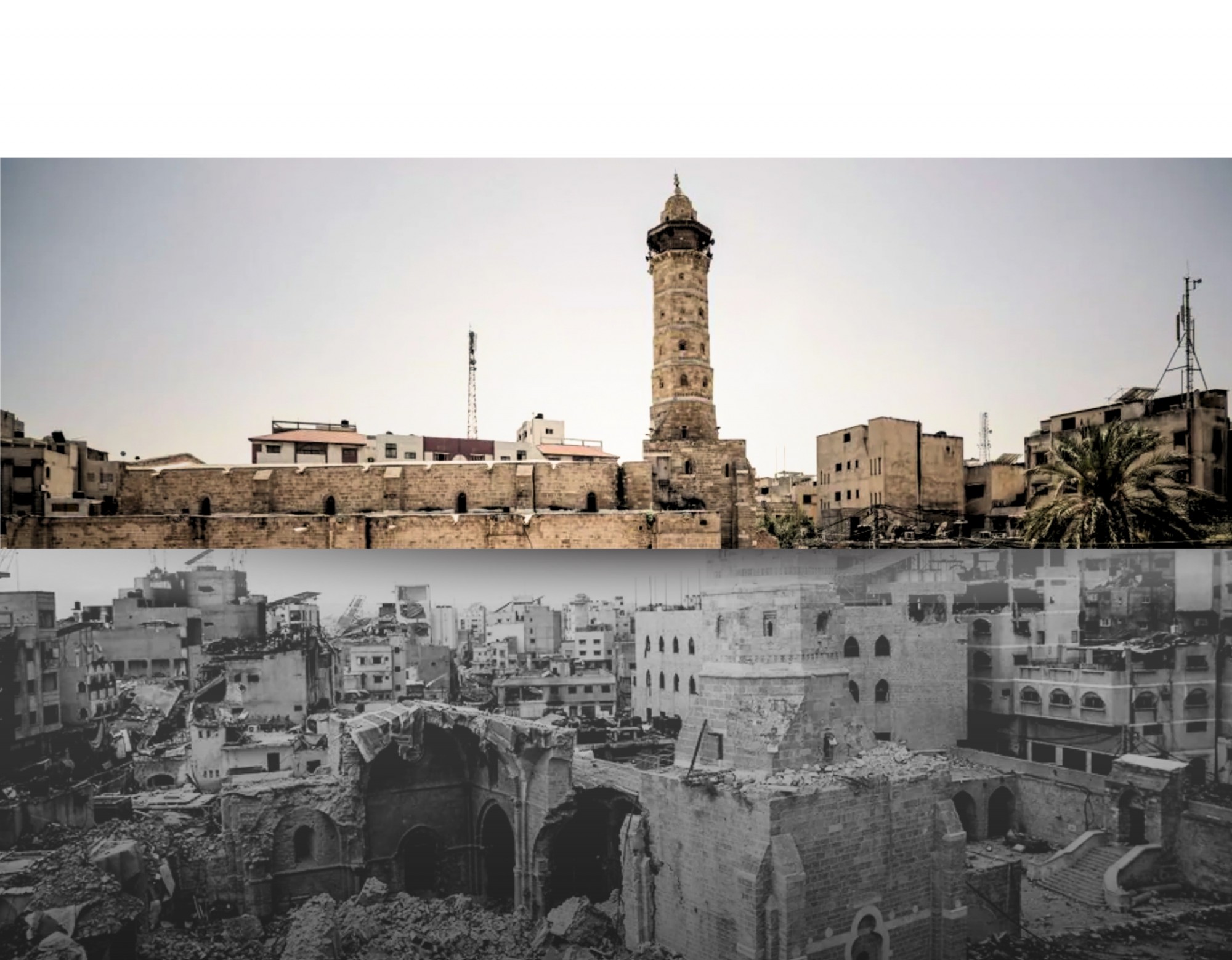

"After migrating to Istanbul, we're eating the same meals; not much has changed in my daily life. I'm with my family, but still, I can't get the same taste because we're far from home." These are the words of Ahmet, who fled the war in Syria and migrated to Istanbul from Damascus in 2019. Ahmet, residing in Fatih, works as an assistant manager in a restaurant selling Syrian-style kebabs. The language he speaks, the music he listens to, the work he does, the social environment he is in, and the food he eats are almost exactly the same as in Syria, but the taste is not the same. Why? How do migrants establish a connection with food, and how does the process of migration impact this connection? Here, we can look at the distinction between food and taste as a starting point. In this distinction, the symbolic values that food gains culturally transform the sense of taste beyond a mere biological or physiological one. That is to say, there is a sociological and cultural explanation for not getting the same taste from the same food, which cannot be explained solely by superficial or environmental factors. With the migration process and the changing sociocultural environment, this sociological phenomenon of taste also changes. These transformations affect not only the migrating but also the hosting societies deeply. In the following sections of the article, we will address different aspects of the relationship between migration and food in Turkey under headings such as the connections migrants establish with food, sociocultural transformations after migration, daily life practices, social integration, and intercultural interaction.

Does Food Create a Shared Identity?

The strong connection between food, belonging and identity stands out when we look at the relationship between migration and food from a sociological perspective. Just like elements such as language, music, clothing, architecture, and religious rituals, food and culinary practices as cultural and social symbols have a profound impact on the creation of migrant identities and the sense of belonging (Haviland, 1999, pp. 42-53). In the aftermath of migration, where the sense of belonging to a place or group is deeply shaken, the bond established with food often functions as a mechanism of resistance. When we analyze different migrant communities both in Turkey and internationally, we observe that migrants construct cultures with plural and mixed identities rather than singular national and cultural identities. Diaspora communities often choose to build new cohesive identities based on shared culinary cultures while disregarding ethnic, religious, and individual differences within themselves (Gasparetti, 2012). Food, especially those with important traditional values, is a fundamental unifying element in constructing new identity practices.

Diaspora communities often choose to build new cohesive identities based on shared culinary cultures while disregarding ethnic, religious, and individual differences within themselves.

It would be more accurate to say that it is not just the food itself but the act of consuming those foods and the shared consumption patterns that transform into a symbol of identity. Because when people consume a dish specific to their homeland together or at the same table, it leads to a sense of group belonging among migrants and fosters an awareness of identity based on cultural symbols (Agutter & Ankeny, 2017). In this process, "reference to the culture of origin," which is a focus for resistance for international migrants, "helps them maintain self-esteem in a situation where their capabilities and experience are undermined" (Castles & Miller, 2008, p. 53). In other words, food practices become a means for migrants or refugees to reconstruct or restore their shaken psychological-cognitive integrity and endangered values after migration. In addition, culinary culture is an important tool for coping with the sense of in-betweenness, frequently referred to in many studies focusing on belonging and identity among migrants, and ensuring cultural continuity.

The Politics of Food

However, the relationship between migration, food, and identity inevitably carries a political character (Fırat, 2024). Especially when nation-culture ideologies and nationalist discourses are prevalent, migrant foods can often be the source of conflict due to the political and ideological meanings attributed to them. For instance, we can look at the use of food associated with immigrant Turkish-Muslim culture, such as kebabs and döner, as a part of political propaganda in ultra-nationalist or anti-Islamic discourses against immigrants of Turkish origin in Europe. For example, the perpetrator of the mosque attacks in Christchurch, New Zealand, in 2019, in addition to publishing a manifesto embracing neo-Nazi ideologies, used the song "Remove Kebab," which became a symbol of Serbian ethnic nationalism during the Bosnian War, as an anthem (Akova & Kantar, 2020). However, elements specific to migrant cultures, especially foods (such as couscous), are often symbolized and used in racist, anti-migrant protests not only against Turks but also against migrant groups coming from Africa or Asia to Europe or the USA. In many examples, we can find different reflections of these discriminatory discourses and policies both at the state-administration level and at the social level (Tuchler, 2015; Uzunçayır, 2014). In Turkey, falafel, which is identified with Syrian refugees and considered a representative of "refugee fast food," seems to have assumed the role of representing Syrian culture and national identity in Turkey, especially in Istanbul (Beylunioğlu, 2023; Alpaslan, 2017).

In Turkey, falafel, which is identified with Syrian refugees and considered a representative of "refugee fast food," seems to have assumed the role of representing Syrian culture and national identity in Turkey, especially in Istanbul.

Interaction Among Intercultural Cuisines

Another important issue in the relationship between migration and food concerns the functions of food in terms of mutual cultural interaction and social integration. The most frequently raised question in this field examines whether food acts as a bridge or a barrier in intercultural communication and integration. When do culinary cultures bring people together, and when do they create divisions among individuals and communities? The primary determinant here is often the performances of culture and identity reproduced through everyday life practices (Goffman, 2018). For example, certain culinary practices such as the types of dishes prepared at home, the choice of restaurants when eating out, setting tables with immigrants from a similar culture, exchanging food with neighbors, and sitting (or not sitting) at the same table with strangers—all signify certain boundaries in the realms of food-belonging-integration within the new migrant culture.

The preservation of culinary culture also means the preservation of one’s community and culture. Because in the modern age, culture is perceived as a "fortress under siege," and refugees (foreigners) are often considered among the groups that should never be fully included in this fortress (Bauman, 2011, pp. 67-68). Therefore, any transformation or loss in culinary practices or culture signifies a loss of a part of cultural belonging. That is why a barrier is consciously or unconsciously constructed against new cultural values or practices while also preserving cultural values. Hence, the interaction between migrant and host communities can also be studied in this context of culinary and intercultural exchanges.

The preservation of culinary culture also means the preservation of one’s community and culture.

When we look at the case of Syrian refugees, who constitute the largest migrant population in Türkiye, we see that Turks and Syrians, who have a high cultural similarity due to factors such as common historical background and geographical proximity, generally approach each other's culinary cultures with prejudice and develop a mutual "palate conservatism" (Onaran, 2015) towards trying different cuisines (Demirel, 2019; Gürhan, 2018). However, when we examine groups gathering around the same table in cafes, restaurants, or neighborly settings, we observe that these prejudices are broken down over time, and sharing meals has a positive reconciliatory effect. As a result of factors such as language barriers between the two cultures, claims of gastronomic superiority, and hate speech, which sometimes rise to the level of gastronomic racism, particularly in the host community, food can function to drive the two communities apart.

In summary, whether forced or voluntary, people who move from their homeland to another place carry more than just their belongings - they also carry their memories and cultures. Therefore, sometimes, a story, a piece of music, or a recipe becomes the most precious possession in the migrant's suitcase. The place certain foods hold in memory, through senses like smell and taste, ensures the continuity of individual and collective memory in the new life after migration. Additionally, as a result of mutual cultural interactions in the culinary realm, not only migrants but also host communities become subjects of sociocultural change. While food practices can sometimes be divisive, they also present a positive starting point for reducing intercultural distance and breaking down societal prejudices.

References

Agutter, K., & Ankeny, R. A. (2017). Food and the challenge to identity for post-war refugee women in Australia. The History of the Family, 22(4), 531-553.

Akova, S., & Kantar, G. (2020). Kültürlerarası iletişim bağlamında nefret söylemi ve Christchurch kenti cami saldırıları örneklemi üzerinden bir söylem analizi. Anadolu University Jornal of Social Sciences, 20(1), 45-260.

Alpaslan, K. (2017). İstanbul mutfağında yeni moda: Mülteci fast food! Retrieved from www.gazeteduvar.com.tr/hayat/2017/01/31/istanbul-mutfaginda-yeni-moda-multeci-fast-food/

Bauman, Z., & Bauman, L. (2011). Culture in a liquid modern world. Polity Press.

Beylunioğlu, A. (2023). Politik bir aktör olarak: Falafel. Aposto. Retrieved from https://aposto.com/s/politik-bir-aktor-olarak-falafel

Castles S. Miller M. J. Bal B. U. & Akbulut I. (2008). Göçler çağı: modern dünyada uluslararası göç hareketleri. Istanbul: Istanbul Bilgi University Press.

Demirel, Ş. R. (2019). Göç mutfağı: Konya’daki Suriyeli göçmenlerin mutfak kültürü (Master’s Dissertation). Ankara Hacı Bayram Veli University, Ankara.

Gürhan, N. (2018). Migratory kitchen: The example of Syrians in Mardin. Journal of Sociological Research, 21(2), 86-113.

Fırat, M. (2014). Yemeğin ideolojisi ya da ideolojinin yemeği: Kimlik bağlamında yemek kültürü. Folklore / Literature, 20(80).

Gasparetti, F. (2012). Eating tie bou jenn in Turin: Negotiating Differences and Building Community Among Senegalese Migrants in Italy. Food and Foodways, 20(3-4), 257-278.

Goffman, E. (2018). Günlük yaşamda benliğin sunumu (Trans. Barış Cezar). Istanbul: Metis Publishing.

Haviland, W. A. (1999). Cultural anthropology. New York: Harcourt Brace College.

Kuzmany, S. (2011). Almanya ve döner. Bianet. Retrieved from https://m.bianet.org/bianet/dunya/134161-almanya-ve-doner.

Onaran, B. (2015). Mutfaktarih: Yemeğin politik serüvenleri. Istanbul: İletişim Publishing.

Tuchler, M. (2015). “Sì alla polenta, no al cous cous”: Food, nationalism, and xenophobia in contemporary Italy (Senior Dissertation). Duke University, Durham.

Uzunçayır, C. (2014). Göçmen karşıtlığından İslamofobiye Avrupa aşırı sağı. Journal of Political Sciences, 2(3), 135-152.

Weber, G. A. (2012). Almanya “döner cinayetleri”ni sevmedi. Bianet. Retrieved from https://m.bianet.org/bianet/dunya/135552-almanya-doner-cinayetleri-ni-sevmedi

Zeynep Yılmaz Hava

Born in Istanbul in 1990, Zeynep Yılmaz Hava graduated from Maltepe Kadir Has Anatolian High School in 2008. In 2013, she completed her bachelor's degree in translation studies at Boğaziçi University with high honours. In 2017, she received her Maste...

Zeynep Yılmaz Hava

Zeynep Yılmaz Hava