In the contemporary geopolitical landscape, soft power and nation branding have become integral for countries and communities aiming to project a positive global image. This process involves showcasing a nation’s culture, values and achievements through various platforms, including cultural events, organisations, and the work of renowned artists. One of the most effective ways to achieve this is through the promotion of Contemporary Art, which has become a significant trend in the world of artistic creations and creative industries.

Contemporary art has the unique ability to transcend borders and connect diverse cultures. In this regard, contemporary Islamic art has emerged as a potent tool for nation branding, highlighting the rich cultural heritage and creativity rooted in the Islamic world. This art form brings contemporary Muslim issues and values to the forefront of diplomatic, business, cultural, religious and international contexts.

This article aims to explore the primary policies of key stakeholders in the Middle East and Western Asian countries, specifically Türkiye, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, in the field of Contemporary Islamic Art. It examines the strategies these countries employ to enhance their soft power and nation brand through this cultural form. The central question is: What image does contemporary Islamic art project for Muslims as a global community and a grand nation?

Soft power is the ability of a country to influence its global audience through its culture, diplomacy, enterprise, and education (Nye, 2021). By promoting contemporary Islamic art, nations can effectively challenge stereotypes and misconceptions about Islam and its followers, fostering a more nuanced understanding of their culture and values.

The Need for Muslim Nation Branding

Temporal identifies three main reasons why Muslim nation branding is necessary. Firstly, Muslim nations face similar challenges and need to differentiate themselves in an increasingly competitive world. Secondly, countries must adapt to survive in a changing world, as past reputation does not always guarantee future success. Lastly, brands are strategic assets that can bring power and financial rewards. They can help countries attract talent and expertise, retain their best citizens, and manage perceptions to address national concerns. This is particularly

relevant to Muslim countries, where differentiation is lacking, images are unclear, and the country-of-origin factor can often negatively impact exports and domestic sales (Temporal, 2011).

A Discursive Typology of Middle Eastern Art

Before examining the role of contemporary Islamic art in the Middle East, it is crucial to understand the evolution of modern and contemporary Islamic art in the region. According to Moridi, modern Islamic art is not an “artistic style” but a “cultural discourse” that changes in social and political contexts. Six cultural discourses have shaped modern Islamic arts: Orientalism, Nationalism, Returnism, Fundamentalism, Globalism, and Middle Easternism. These paradigms have experienced historical sequences but are still current, leading to a complex situation with a multi-paradigm that shapes contemporary art in Islamic countries (Moridi, 2023).

In the orientalist discourse, Islamic art became musealised, defined, classified, and exhibited through a Western lens. This approach often classified Islamic art as decorative crafts rather than artworks, leading to the perception of Islamic art as “non-art” or applied art (Naef, 2015).

“In the name of Allah, the Most Merciful and Compassionate”, Jalil Ziapour’s calligraphy in the form of ibibik, Stedejelik Studies

The nationalist discourse saw the emergence of Pan-Turkism, Pan-Iranism, and Pan-Arabism, with national institutions fostering national identity. Artists used ancient motifs and folk embellishments to create a national art style that represented the nation’s image. Artists such as Nurullah Berk in Türkiye, Jalil Ziapour in Iran, Jawad Saleem in Iraq and Seif Wanly in Egypt were some of the prominent figures of this approach (Moridi, 2023).

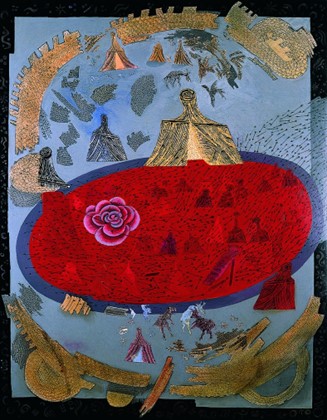

The returnist discourse emerged as a solution to conflicts between Islamists and nationalists in the 1960s, leading to a liberal Islamic approach in policy and culture and a hybridity of traditionalism and modernism known as neo-traditionalism. The Saqqakhana school in Iran, and calligraphical-paintings; based on the Hurufiyya movement heritage and Islamic calligraphical legacy in a modern painting sense, are two innovative outcomes of such a discourse. Artists like Hussain Zenderoudi and Faramarz Pilararm from Iran, Wijdan Ali from Jordan, Erol Akyavaş and Abidin Elderoğlu form Türkiye are some famous artists of the Returnism discourse (Moridi, 2023).

The fundamentalist discourse saw political Islam become the main issue, with art of war becoming the main focus in a region rife with domestic, inter-regional, and international wars. Accordingly, they set up events, such as festivals, established museums and artistic institutions such as Contemporary Art of Palestine Museum in Iran to promote this view, especially in the binary opposition of Palestine-Israel.

The global discourse, initiated in the 1990s; aimed to link traditional, religious, mythical, and logical ideas with universal modernism, emphasising metaphysics and mysterious realism in the form of abstract and geometrical patterns. Artists such as Ahmed Mater from Saudi Arabia, Mattar bin Lahej and Hassan Sharif, and Najat Makki from Emirates are among the famous artists of this approach. The features of this trans-modern art are: creating space of Islamic motifs by installation art as a new sacred public space open to everyone, digitalisation of Islamic art in project mapping, and creating space of light and shadow (Moridi, 2023).

The most recent discourse, Middle Easternism, is not a religious identity but a geopolitical and strategic concept. This type of art is post-modern or post-Islamic and focuses on critical themes on religion, gender issues, ideological relations between religion and policy, and disoriented identities such as art of the Muslim diaspora. Artists such as Abdulnasser Gharem from Saudi Arabia, Faig Ahmed from Azerbaijan, Shirin Neshat and Soodi Sharifi from Iran are few famous names to mention (Moridi, 2023).

Erol Akyavaş, Karbala, 1983, Galeri Nev Istanbul

Discursive Nation Branding Approaches

Contemporary Islamic art, which began in the 1960s, developed in the 1990s, and boomed after 2000, has experienced several discursive practices by nations and artists. From Orientalism to Middle Easternism, countries in the region have activated the potentials of contemporary art to attract tourists, improve investments and education, and create a new cultural identity and reputation using Islamic and regional concepts.

In this arena, two main practices are prominent. The first involves pro-Islamic artists using contemporary arts to draw global attention to valuable Islamic concepts, rituals, sights, landmarks, events, and other potentials of Islamic culture and lifestyle. The second involves artists critically speaking through their artworks on global issues in the Islamic world and nations, including gender, political, social, environmental, and religious concerns.

In both ways, contemporary art draws attention to the themes and subjects it covers. It depends on how countries are hegemonising the issues through events and exhibitions. Some countries have had a more global and liberal approach, leading to the increase of their soft power, while others have practiced more fundamentalist and traditional approaches, decreasing their soft power in global indexes and their reputation.

By promoting contemporary Islamic art, nations can challenge stereotypes and misconceptions about Islam and its followers, fostering greater understanding and appreciation for the diverse and vibrant culture of the Islamic world. As the world becomes increasingly interconnected, the role of contemporary Islamic art in nation branding will only continue to grow in importance, shaping global perceptions and fostering cultural exchange for years to come.

Muslim nations must hold mega art events in the region, supporting young artists to create innovative arts inspired by Islam from their local and shared values. Touring the selected works and presenting them in famous world museums through intelligent curatorship, telling stories and casting images about shared rituals and values of Muslims enhances the soft power of the Islamic World and the branding of Muslims as a unified respected Ummah.

References

Moridi, M. R., & Moridi, B. (2022). Islamic art, exhibitionary order, world exhibitions, art biennials, contemporary Islamic art. Negareh Journal, 17(62), 117-129.

Naef, S. (2015). Questioning a successful label: How ‘Islamic’ is contemporary Islamic art? R. Oliveira Lopes, G. Lamoni, & M. Brito Alves (Eds.), In Global Trends in Modern and Contemporary Islamic Art (pp. 95-107). Portugal: University of Lisbon.

Nye, J. S. (2006). Think Again: Soft Power. Foreign Policy. Retrieved from: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=3393

Nye, J. S. (2021) Soft power: The evolution of a concept. Journal of Political Power, 14(1), pp. 196-208.

Temporal, P. (2011). Islamic branding and marketing: Creating a global Islamic business. Singapır: John Wiley & Sons (Asia).