Representation of Women in Media and True Professionalism

The concept of womanhood exists in almost all societies as a predefined, subtle, but also inevitable codification. This codification corresponds to one of the meanings of the concept of gender, and although it varies from culture to culture, the construction of womanhood is becoming increasingly similar, especially in the modern world.

According to French thinker Pierre Bourdieu, gender in media is a form of identity obtained through solidification. Bourdieu uses the concept of habitus also for media and discusses how media creates its own habitus (Bourdieu, 2000). Fast production techniques are essential in the media habitus, which operates with a vast system of symbols, patterns, and clichés to maintain this pace. We encounter a true solidification when we examine women and media habitus together. Perhaps the most frequently used stereotypes and clichés in media productions are in the field of gender. Moreover, media, which is closely associated with capitalism and consumer culture, inherently produces content about women with the aim of consumption. As a result, global capitalism has largely standardized media content for women and their representation across the world.

The prevailing narrative in media centers around men, with news positioned at the top of the narrative hierarchy and often appearing almost as a “soap opera hour” for male audiences.

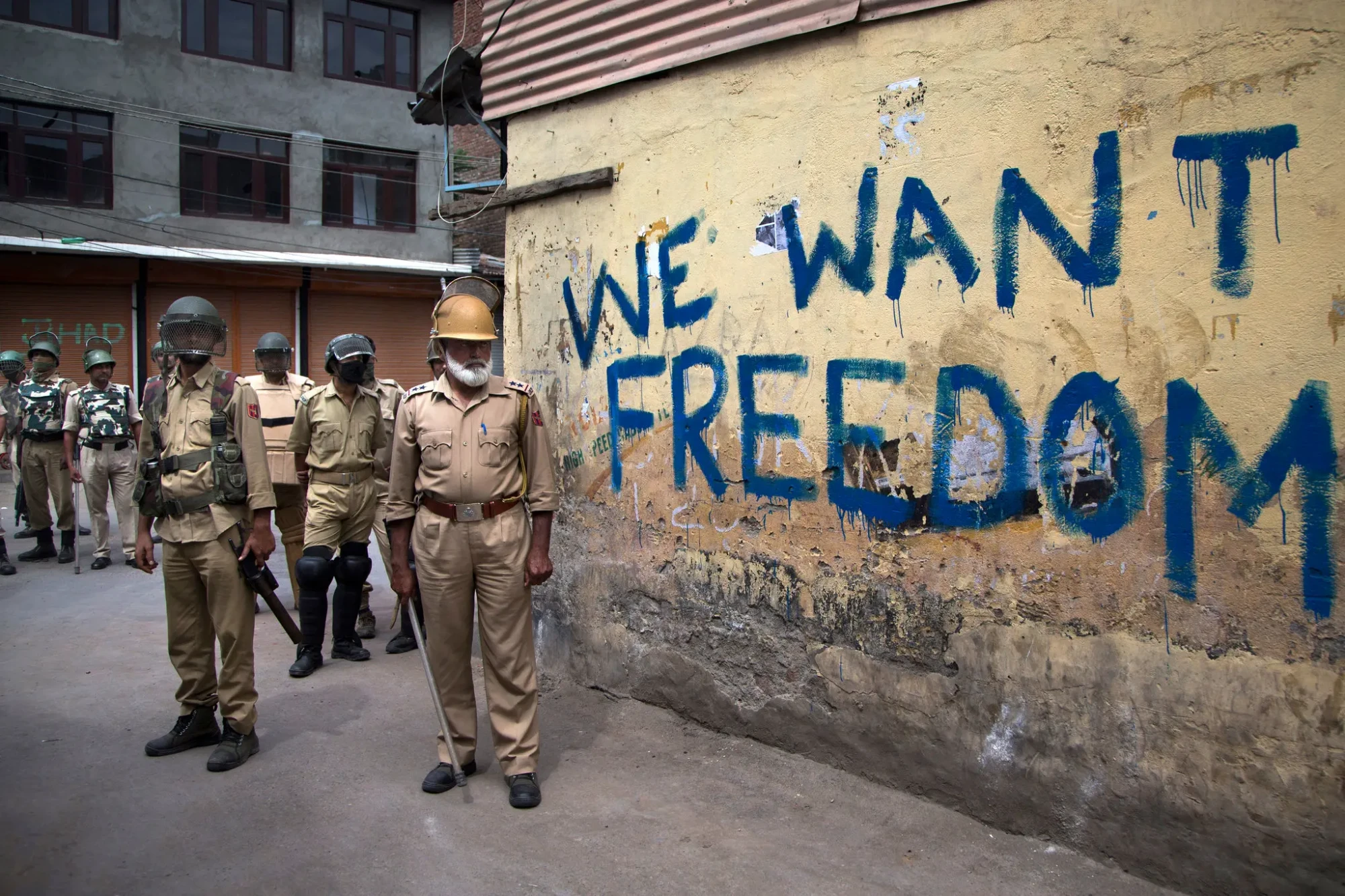

The prevailing narrative in media centers around men, with news positioned at the top of the narrative hierarchy and often appearing almost as a “soap opera hour” for male audiences. This narrative framework dictates what qualifies as news, and children, women, the elderly, and the impoverished are excluded from this framework. News generally targets adult, white, middle-class, middle-aged, married, white-collar, and non-disabled men (Alankuş, 2012).

On the other hand, the representation of women in media is a complex issue that requires nuanced consideration. We have already mentioned that the main narrative in media habitus is created for men and that consumer culture heavily influences the representation of women. In his book Media and Society, Michael O'Shaughnessy explains that “re”presentation is a form of expression through repetition. Given that media is an intermediary realm that cannot be accessed directly, fictional differences emerge between the represented and the representation (O'Shaughnessy, 1999, p. 40). When women appear as subjects in the news, they are often depicted as victims. Women occupy 19% of news coverage as victims, compared to men at 8% (Alankuş, 2012).

Generally, women featured in the news are victims of rights violations, with cases of harassment and rape frequently recounted, resulting in substantial breaches of rights and privacy. Similarly, in reports of femicides, detailed information about the victim and her family is scrutinized, while little is known about the perpetrator and his family. From a journalistic perspective, it is the victimhood, rather than the perpetrator, that is the “sexy.” The situation is no different in TV series. Among thousands of female characters, those representing "good characters" are usually depicted as gullible, passive, compliant, and obvious victims. Betrayed women are portrayed as victims, with another male character often intervening to safeguard their rights. In TV series, women who are portrayed as equals to men are typically depicted as single.

Women occupy 19% of news coverage as victims, compared to men at 8%

Flag Bearers and the Disheartened

As outlined earlier, the media functions within a framework of representations and symbols. Within this set of symbols, there are ready-made packages for specific occasions, such as Mother's Day, Women's Day, and the Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. Women are coded as simple consumers and selective buyers, and on these days, women suddenly transform into superheroes. Screens are filled with examples and stories of women who carry domestic responsibilities, are mothers, do not neglect their husbands, care about their appearances, and have excellent careers and education. Being a woman is often equated with the need to excel in all these domains. However, inevitably, these scenarios often foster an atmosphere of pressure-driven validation rather than making women feel good about themselves. The stories of these exemplary women may sometimes be based on extraordinary realities. These narratives, such as “You must be both a mother and have a fit body, your children should not prevent you from having a career and being successful in business, you should reward yourself with regular shopping and self-care, and you should not neglect your family.” are rooted in consumer culture and challenge women rather than being success stories. Hence, while these flag bearers of such idealized femininity fill the screens, it perpetuates a disheartening and negative sentiment for millions of women in reality.

Women’s Slot and the Violation of Privacy

Throughout the world, daytime TV programming, often known as the "women's slot,” is reserved for topics such as family, health, beauty, cooking, childcare, and personal care. These time slots, which are targeted towards women, confine women to specific content. These programs reinforce traditional gender roles in areas such as cooking, marriage, fashion, and beauty. They provide clear guidelines on how women should behave, appear in roles like mother, daughter, bride, and wife, and how they should present themselves (Akbulut, 2004). The hosts, who stand out with their personal stories, families, and lifestyles, swiftly switch between entertainment and drama. Despite the extensive discussion of these areas related to women, real issues such as property ownership, voting rights, and learning about their legal rights are rarely addressed in these programs.

In recent years, daytime TV shows have taken on the mission of criminal investigation and exposing social violence. The exposure of such issues in these programs has brought domestic violence to a new level. While marginal stories, family dramas, shocking crimes, and tragic murders presented on these shows create the perception that these events are happening everywhere, every day, they also turn domestic violence into a form of entertainment and an opportunity for commercialization. Topics that were once kept private and discussed discreetly among the elderly are now revealed in great detail on daytime TV at a time when children might be watching and brought into the public sphere.

Representation of Labour in the Media

Women working behind the scenes in the media are subject to a different kind of representation. Production processes in media usually involve urgent deadlines and constant pressure for publication. As a result, there are excessively long working hours and a highly stressful work environment. Relationships that develop through social environments called meetings, obsession with being constantly accessible, and working late into the night are viewed as part of "true professionalism" and are not questioned by anyone. There is a general belief that media professions are unsuitable for women and that women cannot keep up with this pace while maintaining a family life. When we examine this widespread view, it becomes clear that family life is considered relevant only for women, while it is deemed normal for men to live in violation of family life. Therefore, there is no ground to discuss the necessity or humane need for weekend or late-night meetings, frequent travel, and excessive overtime for men. On the other hand, due to the challenging working conditions, women working in the media sector are the professional group most likely to take breaks in their careers. As a result, it is common for women working in media to be under 25, live in urban areas, and be single.

Finally, the media industry employs a significant number of women, which may seem positive at first. However, women are often found in middle management roles and do not rise higher (İnceoğlu, 2004). They are more likely to work in lower-level positions, with only a few making it to top management or decision-making positions like chief editors. Furthermore, female managers are often concentrated in areas like advertising supplements or magazines with content focusing on women and children, education, cooking, and advertising.

References

Akbulut, T.N. (2004). Türk televizyonunda kadın söylemi. Kadın Çalışmalarında Disiplinlerarası Buluşma, 2, 157-162.

Alankuş, S. (Ed.). (2012) Kadın odaklı habercilik, Istanbul: IPSCommunication Foundation Publications.

Bourdieu, P. (2000). Televizyon üzerine [On Television]. Istanbul: YKY.

İnceoğlu, Y. (2004). Medyada kadın imajı. Kadın Çalışmalarında Disiplinlerarası Buluşma, 2, 11-20.

O'Shaughnessy M. (1999). Media and society: an introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Meryem İlayda Atlas

TRT Yönetim Kurulu Üyesi olarak görev yapmaktadır. Halen İstanbul Üniversitesi'nde doktora öğrencisidir. Medyada çeşitli alanlarda çalışmış ve gazetecilik yapmıştır. Evli ve bir çocuk annesidir....

Meryem İlayda Atlas

Meryem İlayda Atlas