Seeing Pain: On the Visual Representation of Disaster and Online Censorship in Social Media

“By the witness and what is witnessed…”

(Surah Al-Buruj, 85:3)

Social media is a platform where visual content can spread rapidly and reach large audiences. Therefore, the visuals shared on social media significantly influence the perceptions and emotional responses of the viewer. Today, social media also reminds viewers of their ethical and political responsibilities by exposing distant sufferings.

In social media, which is considered one of the most powerful and fastest communication tools today, visual content from areas undergoing conflict, disaster, or human rights violations plays a critical role in raising global awareness, or in other words, in bearing witness and being witnessed. However, social media platform executives sometimes aim to prevent the spread of such content by applying censorship for different reasons and to make such events "invisible." Hence, the censorship of such content brings along important ethical and political debates.

Watching Others' Suffering from Social Media

"Yes, and how many times can a man turn his head

and pretend that he just doesn’t see?"

(Blowin’ in the Wind, Bob Dylan)

In her book The Spectatorship of Suffering (2006), Lilie Chouliaraki explores how the media's ability to bring distant suffering into our homes influences viewers' responses to this suffering and their sense of public responsibility. Today, the aestheticization and dramatic presentation of suffering on social media significantly affect users' (viewers') sensitivity to pain. Building on Chouliaraki's idea, it can be argued that the constant repetition of tragic events on social media might lead to a lack of empathy among viewers and turn suffering into a form of pornography. In such a case, the aesthetic and dramatic presentation of pain might cause viewers to perceive tragedy as a form of consumption, thereby weakening the impact of real suffering.

Similar to the relationship between photography and human rights, the visuals used on social media can sometimes be seen as sharper, more direct, and more explicit than words in documenting human rights violations and raising public awareness, yet also as manipulative, contextless, and brutal tools. On the other hand, witnessing the suffering of others on social media, with its endless flow, is renewed with every swipe, offering limitless potential for viewing. Thus, distant sufferings are at risk of becoming just one of the millions of consumable content. In this endless stream, the most personal, most private images, which belong to people whose names we don't even know, circulate continuously. In moments when distance and respect suddenly disappear, and emotions such as disgust, contempt, shame, anger, and pity emerge, one of the most fundamental elements of public life also vanishes: "Respect."

According to Byung-Chul Han, what distinguishes respect from merely looking is distance, and a society without distance and respect is heading toward becoming a society of scandal (2024, p. 12). However, distance is quite blurred on social media because these platforms, conditioned by constantly being under surveillance and putting others under surveillance, mix the private and public, the personal and social. For instance, when a visual content from a public account gets reactions (for various reasons), people often justify this lack of distance with statements like "If you didn't want it public, you shouldn't have shared it; if you did, you must accept the criticism." digital communication enables affective discharge right away. On the basis of its temporality alone, it conveys impulsive reactions more than analog communication does. In this respect, the digital medium is a medium of affect" (Han, 2024, p. 13). Social media reinforces this by providing an endless flow of content that blurs the lines between personal and public, near and far. Responses to the Israel-Palestine conflict on social media provide a great example of this. Users encounter a mix of peaceful protests, brutal violence, and emotional calls on the same platform, creating a chaotic environment where empathy can easily turn into voyeuristic consumption or superficial activism. Here, Luc Boltanski's (1999, pp. 3-7) critique of the "politics of pity" becomes relevant. According to Boltanski, in the context of the politics of pity, the urgent action needed to end suffering always prevails over considerations of justice. From this perspective, the need for immediate action to alleviate suffering (in today's context, the need for a "ceasefire") becomes the most urgent issue.

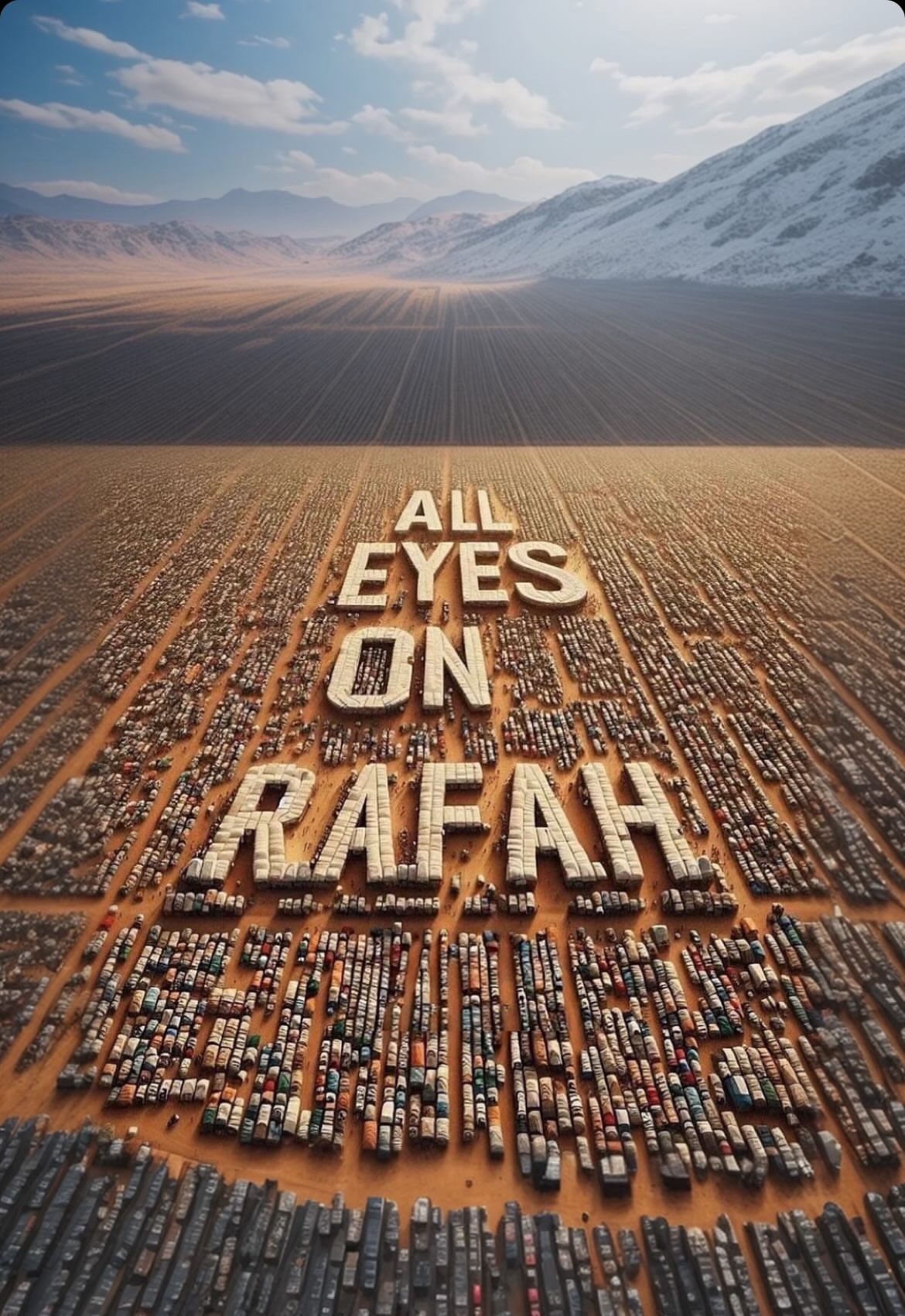

However, the feeling of pity can sometimes lead to a form of narcissistic empathy, where viewers believe they have done enough by merely acknowledging the suffering. This is evident in social media behaviors where users share visuals, post supportive hashtags, or engage in "performative activism," which involves reducing complex issues to a simple post without engaging in any substantial public action. The most recent example of this debate came with the hashtag "All eyes on Rafah" after the bombing of the tent city known as the "safe zone" on May 27th, where hundreds of civilians were sheltering, followed by this image produced by artificial intelligence:

"All Eyes on Welfare" image that went viral on social media.

This AI-generated viral image depicting a vast expanse of tents in a dusty field was shared more than 40 million times on Instagram. It was shared on Instagram stories with a single click; users could see which of their friends had shared the post, and they could add their names to the list. However, the widespread sharing and engagement with this image also sparked some controversies. For instance, some argue that such posts may mark people as passive spectators of others' suffering and ignore the fact that we have other options other than watching. Furthermore, we should also keep in mind that focusing on the question of what we can do about the suffering of others is as important as why it is important to "see" and "show" the suffering. Yet, this is not easy. We live in a society where private feelings are a measurement for perceiving and evaluating the world and others, as Chouliaraki points out, and the media reflects this in various ways every day. We are so preoccupied with emotions, relationships, stories, bodies, and appearances related to "us" through the media (events like the Met Gala, Oscars, Cannes, Eurovision, Memorial Day, Championship Matches, etc.) that the suffering and needs of those who are distant from us turn into mere spectacles in our living rooms. We are unable to see beyond our own issues, yet a simple truth remains clear: our actions have a greater effect when they are directed toward those whose basic needs are neglected than when directed toward those who do not share our common values, thoughts, feelings, lives, and desires. In this sense, while watching the distant sufferings on social media, there is a need to adopt a more comprehensive and critical approach that not only evokes pity but also calls for justice and action.

Both the images and social media have a strong and activist aspect in documenting, proving, creating memory, and storytelling, which becomes particularly meaningful when it comes to the effort to give voice to the voiceless.

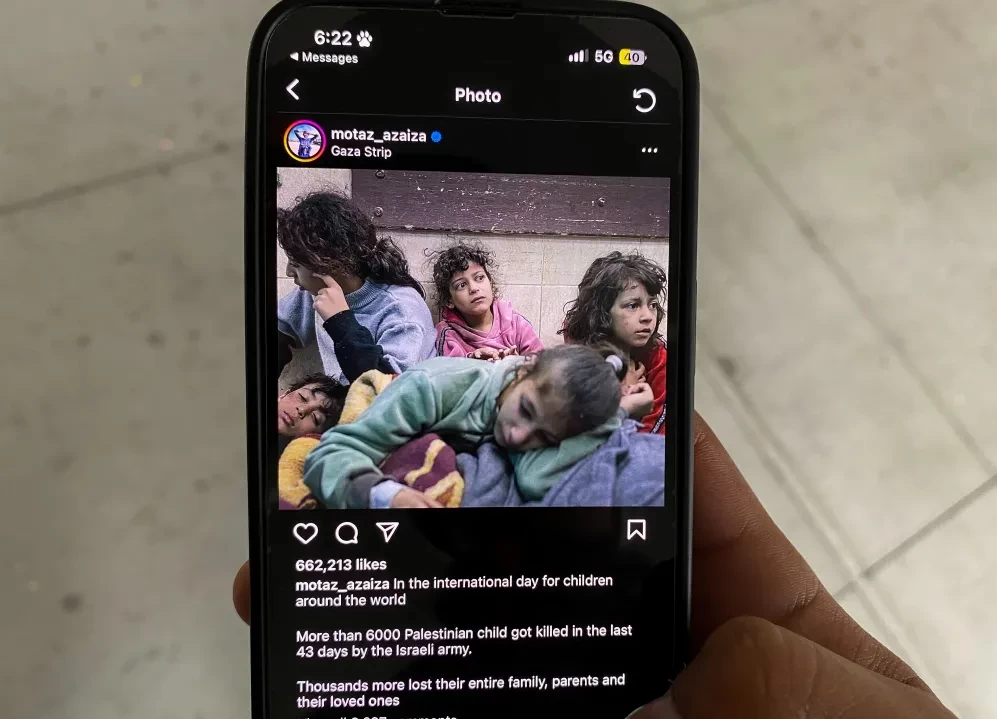

In her work Regarding the Pain of Others (2004), Susan Sontag contends that witnessing distant sufferings is a modern experience that creates emotional distancelessness. While suggesting that this experience is formed through the accumulation of content provided by specialized tourists known as journalists, Sontag argues: "Wars are now also living room sights and sounds. Information about what is happening elsewhere, called "news," features conflict and violence— "If it bleeds, it leads" runs the venerable guideline of tabloids, and twenty-four-hour headline news shows—to which the response is compassion, or indignation, or titillation, or approval, as each misery heaves into view. " (2004, p. 16). Of course, we can no longer only speak of content provided by specialized tourists like journalists. One of the most prominent examples is citizen journalism. However, from Sontag's perspective, it is also a part of our relationship with photographs and videos to recognize that these images are always presented to evoke a certain emotional response. Yet, this does not prevent us from questioning viewers' empathy and ethical responsibilities regarding images shared on social media. However, on the other hand, both the images and social media have a strong and activist aspect in documenting, proving, creating memory, and storytelling, which becomes particularly meaningful when it comes to the effort to give voice to the voiceless. As Edward Said also pointed out, being able to write one's own history and tell one's own story has a critical role, especially for marginalized communities. Therefore, the effort of these communities to leave a lasting legacy for the future is not only a resistance but also a struggle for identity and existence. As Palestinian writer Asmaa Abu Mezied noted, everything recorded on phones by people holding onto their phones to share their suffering and struggle with the world is not only to evoke compassion or mercy from others but also important for documenting this oppression and for future generations: "I am writing this for us, not for them. We hold onto our phones for dear life because we have learned the hard way that documenting what we are going through is very important to ensure that our narrative remains alive and remains ours." However, the voices of communities, whose right to construct their own history and narrative are denied, are not only silenced by mainstream media but also by social media today. They are subjected to shadow bans, silenced, and made invisible. Thus, the potential for societal change created by watching others' sufferings is hindered and ignoring becomes a means of escaping complicity.

Against Online Censorship

"You can ban TikTok, take us out of the algorithm

But it’s too late, we've seen the truth, we bear witness"

(Hind’s Hall, Macklemore)

Meta, the company behind platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Threads, and WhatsApp, has drawn attention with systematic censorship practices targeting Palestinian content. Last December, Human Rights Watch confirmed something many users were already aware of: "Online censorship." Researchers examining 1050 cases of online censorship found that Meta systematically censored Palestinian content using methods such as shadow banning, content removal, account suspension or deletion, and restrictions on interaction. Researchers who revealed a systematic model involving censorship such as restriction, deletion, and blocking claimed that Meta removed such content under false pretenses, thus hindering public awareness. Additionally, they noted that even after completing the report, hundreds more cases of censorship continued to be reported, surpassing the earlier 1050 cases. Furthermore, this situation has not only raised questions about the power of social media platforms to control information flow but also led to the emergence of different resistance tactics and strategies against censorship on social media. In this regard, social media users attempted to bypass algorithms using tactics such as using coded language, sharing emojis, or sharing what the algorithm loves and needs most, such as facial images, to outsmart the algorithm.

Activists in Gaza protest against Facebook's censorship of Palestinian content (Mohammed Asad/APA)

Conversations with social media users who suspect that solidarity posts with Palestine are being restricted are featured in a news article in the New Internationalist. These users share some of their experiences on how they deceive the algorithm. For instance, Hamza Ali Shah, a British Palestinian journalist, says, "Let's say I post on football, I'll get 100 plus views, but on Palestine, it's like 50 to 70, especially if it's consecutive posts," and mentions that he now posts irrelevant content in between Instagram stories on Palestine, or waits 24 hours in between posting to avoid censorship. Another tactic that stands out is the use of the watermelon emoji. The watermelon emoji has become synonymous with solidarity with Palestine. The use of watermelon imagery dates back to the time when Israel deemed the display of the Palestinian flag during the 1967 Six-Day War in Gaza and the West Bank as an offense. Palestinians began using the watermelon, which carries the same white, red, green, and black colors as the flag, to circumvent the ban, and today, the watermelon emoji successfully passes under Meta's radar. Lastly, the tendency of the Instagram algorithm to favor posts containing faces has made sharing one's face a popular method of circumventing the algorithm. Climate activist Mikaela Loach has also expressed that showing her face in posts related to Palestine helps the content reach a wider audience compared to visuals directly linked to Palestine's liberation.

In conclusion, the censorship of the visual representation of others' suffering on social media, in other words, the effort to make disasters "invisible," poses serious problems for freedom of expression and information. Such censorship prevents people in conflict zones from sharing their experiences, voices, and struggles for existence and identity with the world. However, despite attempts to suppress it, it is possible to overcome this and see and show the truth - or, in the simple words of James Agee, "the cruel radiance of what is." Nevertheless, the issue ultimately comes down to wishing for an end to this witnessing. As Bob Dylan famously questioned in his song: "Yes 'n' how many deaths will it take till he knows that too many people have died?"

References

Human Rights Watch. (2023). Meta’s broken promises: Systemic censorship of Palestine content on Instagram and Facebook. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/media_2023/12/ip_meta1223%20web.pdf

Walton, A. (2024). Social media users are bypassing censorship on Palestine. New Internationalist. Retrieved from https://newint.org/social-media-censorship-palestine

Han, B. (2024). Sürünün içinde: Dijital dünyaya bakışlar. (Z. Sarıkartal, Trans.). Istanbul: İnka Book.

Chouliaraki, L. (2006). The spectatorship of suffering. London: Sage Publications.

Sontag, S. (2004). Regarding the pain of others. London: Penguin Books.

Abu Mezied, A. (2024). Etrafımızdaki dehşeti neden kaydediyoruz? (C. Bender, Trans.). Vesaire. Retrieved from https://vesaire.org/etrafimizdaki-dehseti-neden-kaydediyoruz/

Aynülhayat Uybadın

2011 yılında Kocaeli Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi’nden mezun oldu. Aynı üniversitede felsefe ve pedagoji eğitimi aldı. Yüksek lisansını Sakarya Üniversitesi, doktorasını ise “1960’lı ve 1970’li Yıllar Türkiye’sindeki Sinemaya Gitme Deneyimlerini H...

Aynülhayat Uybadın

Aynülhayat Uybadın