What Do ICC’s Arrest Warrants for Akhundzada and Haqqani Mean?

On July 8, 2025, the ICC issued arrest warrants for Taliban leaders Akhundzada and Haqqani for crimes against humanity regarding women's persecution since 2021. The warrants highlighted intra-Taliban dynamics, reinforcing ultraconservative legitimacy and provoking defiance, as the Taliban rejected ICC's authority and emphasized their adherence to Sharia law.

Introduction

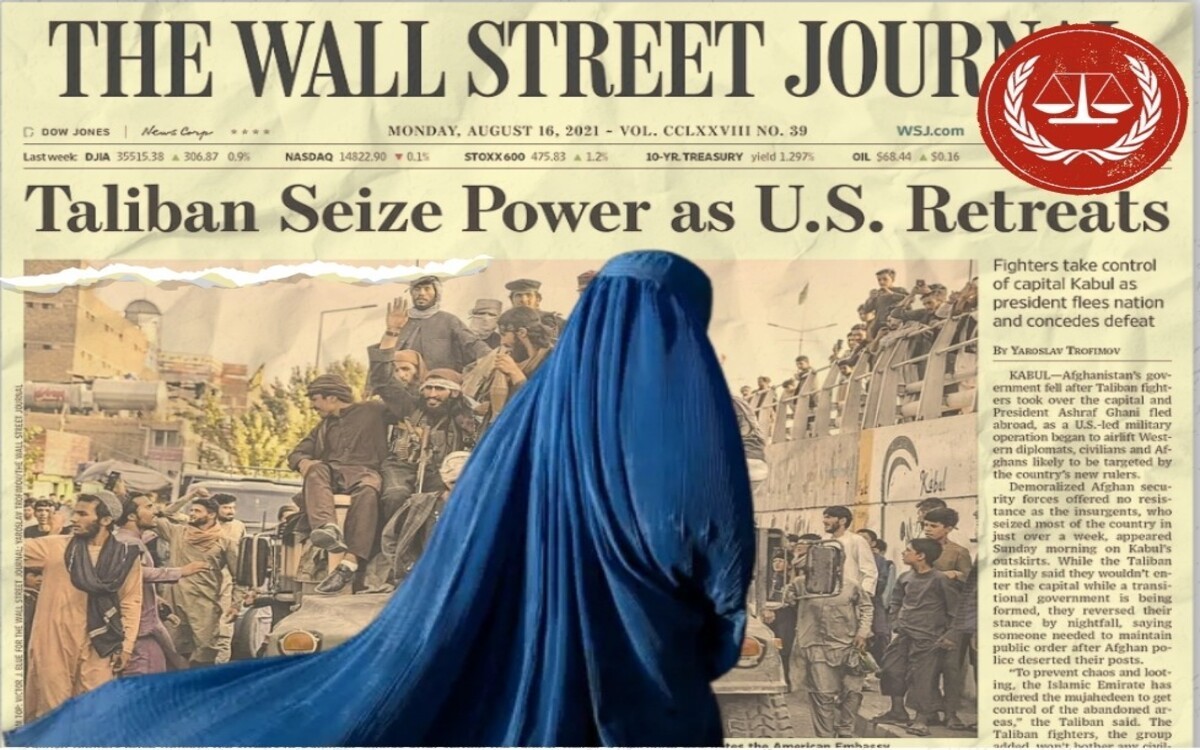

On 8 July 2025, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued arrest warrants for two of the Taliban’s top leadership: Amir Hibatullah Akhundzada and Abdul Hakim Haqqani. The duo was charged with crimes against humanity relating to what it considered the systemic persecution of women since the Taliban’s return to power in August 2021 (Associated Press, 2025). The ICC is hardly a coercive body like the NATO forces that the Taliban ousted from the country. Still, it was the first time an international tribunal recognized gender policies in such terms. The warrant was a victory in an escalating campaign by the Taliban’s opponents to internationalize the new but undefined crime of gender apartheid purportedly in effect in Afghanistan.

The warrant's significance, if not legitimacy, was appreciated in Afghanistan. A flurry of responses from the Taliban veered between defiance, scoffing, and condemnation. A statement by Zabihullah Mujahid, based in Qandahar, denounced the warrant as ‘baseless', reiterating its lack of recognition and rejection of ‘any obligation' to the ‘so-called’ International Criminal Court (Hamd, 2025). The Deputy Interior Minister criticized the perceived double standards inherent in the issuance of the warrant (Arab News, 2025). Privately, Taliban officials, especially those discontented with gender-related policies, remain disillusioned with their international normalization being frustrated.

Who’s who?

Akhundada and Haqqani sit at the helm of two branches of government as Amir and Qazi-al-Quzzat (Chief Justice) respectively. Appraising their importance through the lens of the separation of powers is a rare instance in which Enlightenment-rooted ideals retain any applicability vis-à-vis Afghanistan. Belonging to the same rural Qandahari background that forms the heart of the Taliban, the two also belong to the same ultraconservative faction, the ideological current predominant. The Afghan cabinet may operate in Kabul, but only as a result of Akhundzada’s delegation; his firmans, or decrees, are unbound by other government branches and are issued from Qandahar. Haqqani, meanwhile, oversees the Supreme Court and its overhaul of the country’s judiciary. Although Haqqani seldom appears on camera, his views have been expressed in the public domain through a series of books, in which the ideological convergence between the two is apparent. The foreword to Haqqani’s Imarat al-Islamiyya wa Nidhamuha (The Islamic Emirate and Its System) was written by the Amir, in which Haqqani later discusses the need to limit modern education, both male and female, to fulfill the objectives of the Sharia. Haqqani and Akhundzada’s closeness, evidenced by the latter’s endorsement of the former, indicates a comfortable symbiosis on the most controversial policies.

The ICC’s warrant was therefore a moral assault on the very root of their Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. ICC Chief Karim Khan highlighted both potentially ‘bear[ing] criminal responsibility for the crime against humanity of persecution on gender grounds.’ (Arab News, 2025) The persecution in question related to the Taliban’s restrictions, since 2021, principally relating to bans on girls’ secondary and university education.

Significance

Casting aside its externalities in Afghanistan, the warrant will focus attention on where the duo fits within intra-Taliban dynamics. Much has been made of the cleavage that has assumed public shape since 2021 between the movement’s ultraconservatives, to which the duo belong, and other actors like Interior Minister Khalifa Sirajuddin Haqqani: formerly notorious but increasingly rehabilitated by Western coverage in light of his more permissive stances on women's rights. Khalifa, for instance, has publicly expressed support for girls’ education (Anadolu Agency, 2023) whilst urging responsiveness to public grievances (Associated Press, 2023). Yet far from empowering the now-touted ‘moderates’ like Khalifa, measures seen as exhibiting hostility to Islam will only discredit such actors by association, inversely reinforcing the religious legitimacy of the Amir’s inner circle as embodying true Islamic governance.

The statement of Afghan spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid directly illustrated this; the warrant was ‘a clear expression of enmity and hatred toward the pure religion of Islam and its legal system,’ as well as ‘an insult to the beliefs of all Muslims.’ (Hamd, 2025) Assuming punitive intent, the warrant can only be seen as counterproductive. Insider sources and public pronouncements have repeatedly confirmed that Western antipathy is itself considered a barometer of the group’s ideological truthfulness, at least amongst Akhundzada’s inner circle. The warrant is legitimisation; Taliban statements routinely underscore their monopoly over legal and, more importantly, religious authority in Afghanistan. Not only has Akhundzada routinely spoken in defiance of Western criticism of the country, but he has also reiterated the primacy of what he considers the Sharia (Associated Press, 2025). Gender restrictions are no mere policy choices but religious imperatives and manifestations of sovereignty on which his own legitimacy rests.

Regardless of Taliban internal dynamics, the international fixation on gender demands closer scrutiny. As is abundantly clear in the wake of a genocide and human-engineered famine in Gaza, ‘concern’ is seldom rooted in altruism. Afghanistan is no longer ravaged by war, but still confronted by food insecurity, poverty, and economic sanctions, whilst the ICC has chosen to focus on the persecution of women and girls.

Women’s rights in Afghanistan have long had high visibility in global civil society discourse. Since the end of the occupation in 2021, and alongside their shrinking coterie of Western allies, exiled Afghan figures have highlighted the topic in advocating for punitive measures toward Afghanistan. These include lobbying for isolating its new government and maintaining strangling financial sanctions whilst waging a relentless campaign of online harassment against dissenting Afghans. Predecessors to the gender apartheid campaign included attempts to allege a supposed ‘Hazara genocide’ and a similarly alleged campaign of ethnic cleansing targeting Tajiks. The rare success of the gender apartheid campaign has metastasised it into a political vehicle for the exact figures, reinforcing their goal of internationalising Afghanistan's internal problems and positioning themselves as indispensable interlocutors.

Yet it is undeniable that Taliban policy itself has provided much-needed room for manoeuvre that their woefully discredited foes would not have otherwise enjoyed. An ostensibly temporary closure on girls’ education above the age of 12 was later extended to female university education, both ‘until further notice.’ Concurrently, there has been the proclivity to resuscitate dormant fiqhi discussions, sometimes of centuries past, including on the permissibility of photos (VOA News, 2024), on women’s voices being audible to unrelated men, or on women’s faces constituting awra, or requiring covering (The Guardian, 2024): own goals, and fertile ground for the Taliban’s opponents, domestic and foreign alike.

Into this charged equation and appeal to the Western empire falls the ICC. Already reeling from the geopolitical pressure incurred from its indictment of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (Middle East Eye, 2025), pursuing the Taliban for gender crimes no doubt serves as a useful crutch to balance on. Some would dismiss the Court as embodying the barefaced hypocrisy that has long been embodied in the liberal world order. More accurately, it can be understood, no doubt, as obsolete, to be implementing the furnishings of a world order whose rug is being pulled beneath it, by the same order's founders.

Conclusion

As far as perceptions of the ICC are concerned, it cannot escape what it fundamentally is: a judicial instrument of the West. That is not without reason; the initial impetus for its Afghanistan dossier in 2020, when Afghanistan was still under occupation, included investigations of American war crimes in the country. Khan would subsequently ‘deprioriti[s]e’ these (Associated Press, 2025).

The ICC is indeed seen as the West’s moral empire. Devoid of troops, drones, and B-52 bombers, it is Empire, nonetheless, even embodying its evolution, as evidenced by its own adoption of terminology such as ‘gender identity’ (Associated Press, 2025) in censuring the Taliban, further underscoring the extent to which it operates according to a moral paradigm divorced entirely from Afghanistan.

Ultimately, the grim irony is that the Taliban’s rejection of the ‘so-called’ ICC places it in the unlikely company of two other international pariahs: the United States and Israel.

Bibliography:

Associated Press. (2025, July 8). ICC issues arrest warrants for Taliban leaders over persecution of women and girls. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/icc-tribunal-arrests-taliban-women-36e471179d6059ab1c9ae6699e5082c0

Hamd, M. F. [@FitratHamd]. (2025, July 8). The Islamic Emirate's Ministry of Foreign Affairs condemns the ICC's arrest warrants as biased and legally baseless... [Tweet]. X. https://x.com/FitratHamd/status/1942626167397261444

Arab News. (2025, January 24). Taliban dismisses ICC arrest warrants, says court 'can't scare us'. https://www.arabnews.com/node/2587669/world

Anadolu Agency. (2023, September 4). Taliban urges patience on women’s education. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/taliban-urges-patience-on-womens-education/2983369

Associated Press. (2023, February 16). Taliban minister breaks ranks over girls' education ban. https://apnews.com/article/kabul-united-states-government-taliban-6f34fa4d93635d3500d91918624d4191

Associated Press. (2025, March 31). Afghanistan’s supreme leader: No need for laws from the West; Sharia will suffice. https://apnews.com/article/afghanistan-taliban-western-laws-sharia-c11444b20fbb6c77d2632fae84435af2

VOA News. (2024, October 14). Afghan Taliban vow to implement media ban on images of living things. https://www.voanews.com/a/afghan-taliban-vow-to-implement-media-ban-on-images-of-living-things/7821442.html

The Guardian. (2024, August 26). Taliban bar on Afghan women speaking in public is ‘extremely concerning’, says UN. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/article/2024/aug/26/taliban-bar-on-afghan-women-speaking-in-public-un-afghanistan

Middle East Eye. (2025, August 1). Exclusive: Israel war crimes probe derailed by threats, leaks and sex claims. https://www.middleeasteye.net/big-story/exclusive-karim-khan-israel-war-crimes-probe-derailed-threats-leaks-sex-claims

Ahmed-Waleed Kakar

Ahmed-Waleed Kakar is a British-born analyst and journalist specialising in Afghan political history and current affairs. He is the founder of The Afghan Eye, a media platform offering a critical locally grounded perspectives on Afghanistan's recent ...

Ahmed-Waleed Kakar

Ahmed-Waleed Kakar