There is no doubt that the practice of architecture is as old as human history. In this respect, architecture can be considered the concrete form of the art and space production activities of civilisations in history, carried into the future. Hence, it is not easy to understand, analyse and evaluate architecture shaped by geography, materials, social structure, life practices, beliefs and many other elements. Architectural historians sometimes read architecture through states and civilisations (such as Byzantine Architecture and Islamic Architecture), sometimes through geography (such as Middle Eastern Architecture and European Architecture), and sometimes by dividing it into movements and eras (Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, etc.). Regardless of the title, they evaluate by distinguishing and classifying the standardised and similar spatial elements through the inventories of the buildings they examine. What makes examination and evaluation possible is essentially the “spirit of standards” that the buildings communicate and create through repetitive forms. Only in this way can architectural historians arrive at standard judgements and interpretations of architecture: Flying buttresses point to the Middle Ages, planimetric designs to the Renaissance, curvilinear styles to the Baroque, and geometric ornaments to Islamic architecture. These analyses, which are consistent and correct up to a point, can be accepted as valid until the post-industrial period when the limits in construction methods were greatly exceeded and reviving elements gained momentum. In this article, I attempt to read the Artuqid revivalist works constructed in Mardin in the last twenty years or so in the light of the concept of the invention of tradition through the dichotomies (old-new, interior-exterior, time-space, etc.) brought about by the age.

In contrast to the relatively static, standard, stereotyped forms of pre-industrial architecture, the rapidly changing spirit of the post-industrial period brings an eclectic and stimulating understanding of architecture. In the works of this period, architectural elements do not address the end-user from a single world; on the contrary, each element seems to be the work of its own era in its own world and brought together unconsciously. This way of producing space is quite different from the architectural form that civilisations created in a period of history and repeated for centuries by resembling classical forms. It may look traditional but introduces a new model that refers to different traditions, eras, forms and construction standards. In the post-industrial period, it is common to see elements of medieval Gothic architecture in skyscraper structures[1] or to adapt a temple plan to a parliament building.[2] This is the period when architects can make selective and reviving designs according to the preferences of the end-users without any material, structural or technical limitations, thus far from being standardised. With the misconception that it carries freedom and innovation, this period actually brings along many dualities: Old and new, interior and exterior, time and space. The old is presented renewed; the new is intended to be displayed like the old, so the distinction between what is old and what is new becomes increasingly blurred. The inside is not reflected on the outside, time is independent of space, and the definition of tradition has become ambiguous.

Spatial/historical elements, many of which are produced based on symbols, rituals or practices, can be called traditional. However, in the field of Turkish urbanisation and architectural practice in the last century, what tradition refers to, what it contains, and how it can be traditional are other problems. It is possible to find the old-new binary in the architectural practices of many Anatolian cities. However, this binary has sharply divided some, such as Mardin. This dichotomy is so visible in Mardin that it is possible to divide it into two spatial planes, Old Mardin and New Mardin.

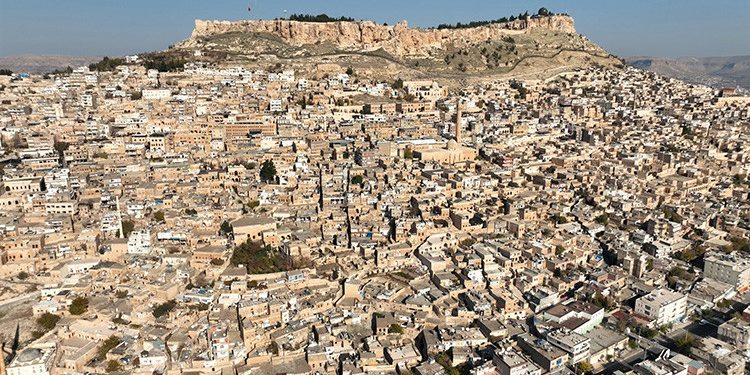

I am aware of the stone hillside houses with rooftop terraces overlooking the Mesopotamian plain that come to mind when one thinks of Mardin. A pair of eyes scrutinising this image realises that Old Mardin is essentially a medieval Islamic city. The city owes its landscape character (albeit heavily influenced by the multi-layered Assyrian culture) to the rapid Arab migration to the region following the Islamic conquests[3] and the constant construction activities that took place in the following centuries.[4] During this period, the urban landscape of Mardin, was dominated by yellow limestone (known as Mardin stone by the society) as a local material, as well as single-storey, vaulted and dome-covered buildings, externally fluted domes, square epitaphs written in maqili calligraphy, spolia including columns and stones, geometric adornments, rumi and palmettes. All these qualities describe Old Mardin. However, the New Mardin, constructed gradually since the 1980s and equipped with multi-storey reinforced concrete buildings where most of today’s urban population resides, is far from this description.

Mardin Yenişehir, Murat Çağlayan Archive

Indeed, there are many concepts to describe the new Mardin: Land rent, high-density housing with storeys up to twenty-five, insufficient green areas, car parks and pavements. In addition, it can be argued that the main factor in the formation of duality in the New Mardin is the practice of referring to the past, which is noticeable in the present buildings and ongoing constructions for the last twenty years. The ancient city of Mardin, which existed in many periods of history, found its true identity, especially during the Artuqid period; therefore, the works constructed in the city in recent years clearly refer to Mardin’s middle age. In New Mardin, Artuqid revivalist artefacts, many built in the last two decades, can be seen as soon as one passes Old Mardin. Some of the artefacts look like and/or refer to Artuqid artefacts with their teardrop motifs, fluted domes and pointed arches. The revivalist works, which find their main characteristics in mosques and public buildings in the city, are exact copies of Artuqid works in terms of elements such as minarets, façade designs and ornamentation or have partial similarities. The District Governorship of Artuklu and the Rectorate of Artuklu University, built in recent years, are notable for their symmetrical façade designs, exterior part covered with a layer of yellow limestone, the stone niches surrounding the façade and the pointed arch windows built in addition to them. Although Muftiate of Mardin is similar to Zinciriye Madrasa and Kasımiye Madrasa with its yellow limestone-clad façade or the triple window arrangement on the façade, it also contains orientalist references with its fluidly shaped parapet and the entrance door railings on both sides.

Muftiate of Mardin (Left) and The District Governorship of Artuklu (Right), Personal Archive

The Rectorate of Artuklu University

In mosque architecture, there are many examples where the minaret of the Great Mosque of Mardin or the minaret of the Şehidiye Mosque and Madrasah are reproduced exactly, or which draw attention with their similarity to the dome of the Great Mosque.

Artuklu University Zeynel Abidin Erdem Mosque (Left), Mardin Yedikardeş Mosque (Right)

Sakir Nuhoğlu Mosque (Left), Fuat Yağcı Mosque (Right), Anonymous

Tümer defines the spatial design in Zeynel Abidin Erdem Mosque as architectural syncretism. Completed and opened for worship in 2020, the building, according to the author, carries examples of Ottoman and Artuqid architecture. The author interprets this situation as both “a reference to the profound history of the city” and “an indication of the deep specialisation and respect for this history” (Tümer, 2021, pp. 133-144).

Artuqid revivalism can also be examined in the construction of apartment/residential areas. The spatial features reflected in the multi-storey buildings may include revivalist elements borrowed from different Artuqid buildings built in the past. Most of these buildings have exterior painting that resembles yellow limestone. Many complexes are equipped with pointed arch windows and palmettes on the façades.

A Building in Mardin Ravza Street, Personal Archive

Whether built in the Artuqid revivalist or Orientalist style, another dichotomy draws attention in recent buildings: In these buildings, the exterior is usually not reflected in the interior. The interior of mosques with classical Artuqid façades lack rumi and palmettes inlaid in stone or carved, as in Artuqid buildings; instead, they are adorned with two-dimensional calligraphy ornaments on the surface. Public and residential buildings, on the other hand, are designed in a rather ordinary, even modern and simple manner.

Interior of The District Governorship of Artuklu, 2021, Personal Archive, 2021

Although I partly agree with the architectural approach that approves referencing the past, my partial abstention is that space is not produced with buildings only. One of the issues that should be addressed regarding revivalist structures that refer to a certain period of history is the invention of tradition. Hobsbawm states that “Traditions that appear or claim to be old are often quite recent in origin and sometimes invented” (2006, p. 1) and defines invented traditions as “a set of practices, normally governed by overtly or tacitly accepted rules and of a ritual or symbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behaviour by repetition, which automatically implies continuity with the past” (2006, p. 3). According to Hobsbawm, what is interesting is that “use of ancient materials to construct invented traditions of a novel type for quite novel purposes” (2006, p. 7). According to him, “A large store of such materials is accumulated in the past of any society, and an elaborate language of symbolic practice and communication is always available. Sometimes new traditions could be readily grafted on old ones; sometimes they could be devised by borrowing from the well-supplied warehouses of official ritual, symbolism and moral exhortation” (2006, p. 7).

Architecture in New Mardin, which still points to the medieval style through contemporary buildings, has taken on a revivalist attitude as a quite new form of construction. This attitude becomes comprehensible in light of the concept of the invention of tradition. These buildings, far from being products of their own era, bring the dualities of new and old, interior and exterior. This situation confirms what Anthony Giddens says in The Consequences of Modernity. He states that in the pre-modern period, space and time were interlinked, but in modern times, with the invention of the mechanical clock, time was separated from space (Giddens, 1994, p. 23). Similarly, the new construction forms can be considered an example of space/place becoming independent from time.

References

Abdüssselam Efendi (2007). Mardin tarihi. Mardin Tarihi İhtisas Kütüphanesi Publishing.

Çağlayan, M. (2017). Mardin’de neler oluyor? Retrieved from: https://www.arkitera.com/gorus/mardinde-neler-oluyor/

Dinç, F. (2021). İslâm inşâ hukukunun Mardin kent mekânına yansıması. Mukaddime, 12(2), 307-346.

el-Belazuri, A. (2013). Fütuhu’l büldan: Ülkelerin fetihleri. (Trans.). Prof. Dr. Mustafa Fayda. İstanbul: Siyer Publishing.

Giddens, A. (1994). Modernliğin sonuçları. İstanbul: Ayrıntı Publishing.

Hobsbawm, E. J., & Ranger, T. (Ed.) (2006). Geleneğin icadı. (Trans.) Mehmet Murat Şahin. İstanbul: Agora Publishing.

Tümer, Ş. (2021). Mimari bir sinkretizm örneği: Dr. Zeynel Abidin Erdem Camisi. In M. K. Keha (Ed.), 6. Uluslararası Mardin Artuklu Bilimsel Araştırmalar Kongresi (pp. . 133–144). Ankara: Farabi Publishing House.

[1] The Chicago Tribune Tower, constructed in the 20th century in America, can be given as an example, along with the Woolworth Building.

[2] Thomas Jefferson: The Virginia State Capitol (1785-1789) was chosen as a model for the Maison Carrée in Nîmes, France.

[3] For detailed information on migrations, see Belazuri.

[4] Abdusselam Efendi‘s treatise is the first comprehensive publication on the history of Mardin. He mentioned the importance of the castle for Mardin’s urban history and stated that Nasrüddevle (1011-1061), one of the Marwanid rulers, built many buildings on the southern slopes of Mardin Castle during his reign (Abdüssselam Efendi 2007). In addition, many steps towards urbanisation on the southern slopes of the Mardin castle were taken during the Artuqid period. During this period, “the southern slopes of the castle, which constitute the urban centre of Mardin, were the scene of intensive public works and construction activities”. (Dinç 2021, 307-346).